Few pragmatic interpretation of scalar implicature studies have been done with settled adult bilingual populations (Dupuy et al., 2018; Antoniou and Katsos, 2017; Slabakova, 2010). Most of these studies have argued, though not conclusively, that bilingual speakers possess advantages in pragmatic interpretation over monolingual speakers. These studies of pragmatic interpretation of existential quantifiers thus far, have been done in major Indo-European child and adult languages, including English some (Contemori et al., 2018; Miller et al., 2005; Smith, 1980); Spanish algunos (Pratt et al., 2018; Grinstead et al., 2010; Vargas-Tokuda et al., 2009, 2008; Lopez-Palma, 2007); French certain (Noveck, 2001); Greek meriki (Papafragou and Musolino, 2003); and Dutch somige (de Hoop, 1995), focusing on pragmatic production by monolingual participants. Furthermore, none of these studies has been carried out in an indigenous language of the Americas. Imbabura Kichwa is an indigenous language spoken in the Northern Andean province of Imbabura in Ecuador. Kichwa, or Imbabura Kichwa, is a Quechuan language variety spoken in the northern province of Imbabura in Ecuador (Gualapuro, 2017; Adelaar, 2004; Muysken, 1992; Cole, 1982).

The structure of this article offers a concise analysis of the pragmatic interpretation of the existential quantifier some and its equivalent existential quantifiers in other languages, such as algunos in Spanish. This study also provides supporting literature regarding studies on the pragmatic interpretation of some in bilingual contexts and the cognitive factors driving it. It introduces the Kichwa existential quantifier wakin and outlines a detailed research methodology, reporting findings from four unique experiments. The first experiment explores the use of wakin among Kichwa-Spanish bilingual speakers in rural areas near Cotacachi and Otavalo in Imbabura. The subsequent two experiments scrutinize the Spanish quantifier algunos among two demographics: Kichwa-Spanish bilinguals and Spanish monolinguals from Cotacachi and Otavalo, and Spanish monolinguals from Quito and Guayaquil, respectively. The final experiment focuses on wakin, with highly educated Kichwa-Spanish bilinguals with substantial technological skills and urban lifestyles. The study culminates in an exhaustive discussion and conclusion of the findings.

1.1 Pragmatic implicatureGrice (1975, p. 43) states that quantity implicatures are generated due to a quantity scale existing in the lexicon. This scale means that the utterance of a given value on a scale will implicate that “as far as the speaker knows, no higher value applies. This scale includes the quantifiers all, many, some, few, and none. In conversational settings, reading between the lines, the quantifier some gets the ‘some, but not all' meaning by being less informative than all (Horn, 1972, p. 70–154).” In other words, if someone says a phrase as in (1), the message implies s/he did not eat all of the cookies.

(1) I ate some cokies.

This study focuses on the “some, but not all” reading; however, some is a pluri-functional quantifier or can be associated with meanings other than the focus reading of this study. Alternative interpretations include using some to refer to someone or something unknown, unspecified, or pragmatically non-identified.

(2) I talked to some doctor the other day, but I do not

remember who.

Sentence (2) is unspecified, unknown, and also pragmatically non-identified. These properties of some provide a door to study them further; however, it is not the topic of interest of this study.

This “some, but not all” interpretation of the noun phrase (NP) is taken to be the result of higher-order reasoning, making an inference in a particular syntactic and pragmatic context, producing an interpretation that Grice (1975, p. 45) referred to as a “scalar, generalized conversational implicature.” The example in (3) below illustrates this interpretation.

(3) Some students passed the exam.

In other syntactic and/or pragmatic contexts, the same noun phrase (some students) can be understood to mean “some, and possibly all”, as in this example 4.

(4) If some students come to my office hours, I'll buy you

lunch.

In sentence (4) the “some, but not all” pragmatic meaning has disappeared and been replaced with the “some, and possibly all” logical meaning, which occurs in syntactic contexts (known as Downward Entailing contexts) such as the antecedent clause of a conditional sentence (Ladusaw, 1979).

1.2 Pragmatic interpretation of quantifiers in EnglishSince Smith (1980) first investigated the quantification of some with English monolingual adults and children, results have told us that adults and children can (on various degrees of acceptance) read the “some, but not all” quantification with the English quantifier some. Though Smith (1980) did not set out to study pragmatic implicature generation or cancellation, it became the first experimental study in quantifiers in English. Her experimental context constituted a downward-entailing context (yes-no questions) in the sense of Ladusaw (1979), which resulted in the logical “some, and possibly all” interpretation of the existential quantifier some being prominent.

In English, it seems to be the case that the phonetic properties of some words play an essential role in their interpretation. Miller et al. (2005) found that the phonetic properties of some could play an important role in shedding the pragmatic interpretation of some. They found that the contrast between (5a) and (5b) below allows a construction of sentences that both contain a weak quantifier but differ in the presence or absence of a quantity implicature. In sentences like (5b), if some is the stressed form SOME, the scalar implicature effect caused by the pitch-accented version seems to be implemented more strongly. Miller et al. (2005) state that “the focus (by the stress) on the quantifier induces the scale as the alternative set.”

(5) a. Make some happy faces

b. Make SOME faces happy

Grinstead et al. (2010) and Thorward (2009) found that some have three phonetically different forms, including the syllabic nasal sm, the full vowel no pitch-accented some, and the full vowel, pitch-accented SOME (see Table 1). Thorward (2009) demonstrated that the three forms of the quantifier some has the following interpretations: the weak form sm with a purely existential interpretation similar to unos in Spanish; the pitch accented SOME that generates the implicature of “some, but not all” and “some, and possibly all”; and the bare form some similar to algunos in Spanish but functioning strictly as a pure quantifier (Grinstead et al., 2010; Thorward, 2009). These variants of some have specific properties concerning word duration, vowel duration, and pitch. Thorward (2009) gave the following means of these variables for each type of some tested.

Experimentally, for implicature generating contexts, Grinstead et al. (2010) showed that English-speaking adults were able to distinguish differences between the SOME and some conditions (χ2 = 5.4, p = 0.02) as well as between the SOME and sm conditions (χ2= 15.8, p < 0.01). Their results also showed significant difference between sm and some (χ2 = 10.5, p = 0.001) and between sm and SOME (χ2 = 19.5, p < 0.001) but not between SOME and some. These results showed that adults “rely heavily on the presence or absence of contrastive pitch accents” to calculate a “some but not all” implicature meaning in English. This study also included children. Grinstead and colleagues found that children can deliver the “some but not all” pragmatic interpretation. However, children rely heavily on cues from vowel realization and do not rely significantly on the placement of contrastive pitch accents. The current work (built on Grinstead and colleagues's findings) explores the possibility of a pitch-accented effect in Kichwa's quantifier wakin. It is expected that the final syllable stressed form [wa.ˈkiŋ] (instead of the canonical penultimate syllable stressed form [ˈwa.kiŋ]) of wakin is the form to generate the implicature interpretation.

1.3 Pragmatic interpretation of quantifiers in SpanishIn Spanish there are two some-like equivalent existential quantifiers; algunos and unos (Gutiérrez-Rexach, 2004, 2001). Gutiérrez-Rexach (2001) notes that “there are significant differences between unos and algunos. The crucial distinction relevant to this study is that unos ‘a-pl' cannot occur as the subject of individual level predicates, whereas algunos ‘some-pl' can Gutiérrez-Rexach (2001, p. 118).” In this line, Vargas-Tokuda et al. (2008) considers that algunos allows a “some, but not all” pragmatic implicature, which “can be canceled in downward entailing environments,” created by the antecedent of a conditional.

The existential quantifier unos appears to “permit truth-conditionally similar some, but not other” interpretations according to Pratt et al. (2018). However, she also states that “through its unos…, otros no articulation,” a collective reading. She argues that unos cannot generate the “some, but not all” interpretation, which aligns with the unos properties as described in Gutiérrez-Rexach (2001)'s studies.

Using the Truth Value Judgement Task method, Vargas-Tokuda et al. (2009) tested 27 monolingual, Spanish-speaking children (Age Range = 4.9–6.7, M = 5.9) from a daycare center in Mexico City, and 10 monolingual, Spanish-speaking adults from the same city. These children and adults could generate the quantity implicature with algunos sentences as in (6) where X are animals.

(6) Algunos X saltaron sobre A

Some-A Xs jumped over A

Her experiment showed that Spanish-speaking adults (80%) could distinguish the differences between unos and algunos. She also found that children “can distinguish unos and algunos at a young age” at the 70% rate (Vargas-Tokuda et al., 2009). These results show that monolingual Spanish-speaking adults could deliver the “some, but not all” pragmatic interpretation with algunos. In contrast to Noveck (2001), they also argue that even 5-year-old children in this study could generate a “some, but not all” pragmatic implicature with algunos.

Pratt et al. (2018) also conducted a more extensive (than Vargas-Tokuda's) experimental design for algunos and unos in Mexico City with 60 college students who were monolingual Spanish-speaking adults (Range: 220–445 months, M = 305.5 months, SD = 63 months) and 42 typical developing children (Range: 61–84 months, M = 69.74 months, SD = 5.42). Their experiments used two Question Under Discussion (QUD) conditions, quiénes (who) and cuántos (how many), under the Truth Value Judgment Task (TVJT) approach (Crain and Thornton, 1998). Results for both QUD forms showed that for quiénes, adult college students generated implicature readings 100% of the time. For cuántos, college student adults generated the implicature reading 94% of the time. Pratt et al. (2018) and Vargas-Tokuda et al. (2009) experiments showed that monolingual Spanish-speaking adults in Mexico City could generate the “some, but not all” reading with the Spanish existential quantifier algunos. The stimuli applied in Pratt et al. (2018)'s research were adapted to the Ecuadorean Spanish context in this project for experiments 2 and 4. This adaptation is a crucial step in ensuring the relevance and applicability of the experiment to the specific linguistic context of Ecuador.

1.4 Pragmatic interpretation of quantifiers in other languagesResearch initiatives focusing on the pragmatic interpretation of quantifiers in languages other than English or Spanish are relatively scarce. One such study was conducted by Noveck (2001), who examined the production of scalar implicatures of the existential quantifier certain (some) among French-speaking children and adults. The results of Noveck's experiment indicated that adults delivered the “some, but not all” interpretation 87% of the time, while children achieved this interpretation 41% of the time. This led Noveck to conclude that children's ability to generate implicature interpretations in French was not yet fully developed in an adult-like way in French.

In a separate study, Papafragou and Musolino (2003) tested Greek children and adults on the interpretation of the Greek quantifier meriki meaning (some) in English. Ten Greek children, five years old (M: 5.3 years old) and 10 adults participated in this experiment for meriki. They used the following type of sentences in (7) as stimuli.

(7) Merika apo ta aloga pidiksan pano apo to fraxti

“ Some horses jumped over of the fence”

Papafragou and Musolino (2003) found that adults generated implicature 92.5% of the time, while children generated the implicature only 12.5% of the time with the Greek quantifier meriki. Based on these findings, they proposed that preschoolers, and children in general, do not appear to be as sensitive to the pragmatic interpretation of scalar terms as adults.

Both studies (Papafragou and Musolino, 2003; Noveck, 2001), demonstrated that adult speakers of other languages (French and Greek, in addition to English and Spanish) were capable of generating the “some, but not all” scalar implicature with their language's equivalent of some. It is anticipated that this experimental study involving Kichwa adults will also yield the “some, but not all” implicature interpretation with the Kichwa quantifier wakin. This forthcoming experiment has the potential to enrich the existing body of research on the pragmatics of quantifiers in languages that are not traditionally studied.

1.5 Bilingualism and cognition in scalar implicature readingSociolinguistic variables can become predictors of linguistic knowledge, interpretation and social distinction, (Eckert, 2012; Labov, 1972, 1966). Education level, linguistic background, and access to technology are some of the critical variables studied in language production (Dupuy et al., 2018; Syrett et al., 2016, 2017; Slabakova, 2010).

The relevance theory postulated by Sperber and Wilson (1995) states that interpreting implicatures involves extra cognitive effort, in opposition to the literal meaning mentioned by Antoniou and Katsos (2017); Prior (2012) and Pouscoulous et al. (2007). Studies have suggested opposing results (positive and negative) for the effects of bilingualism on cognitive functioning (Cockcroft et al., 2019; Contemori et al., 2018; Antoniou and Katsos, 2017; Marton et al., 2017; Bialystok, 2015, 2001; Barac and Bialystok, 2012). Language production and cognitive abilities in monolinguals and bilinguals have been studied thoroughly; however, Antoniou and Katsos (2017, p. 2) mention that “pragmatic-communicative skills have so far received little attention”.

Siegal et al. (2007) tested Italian-Slovenian bilingual children's interpretation of scalar implicature in Italian. In this test, bilingual children also performed better than monolingual children. They also repeated the test with Italian-German bilinguals in Italian in 2010 and obtained similar results; bilingual children performed better than monolinguals. Further, Siegal et al. (2007) explored whether bilingualism confers an advantage to pragmatic competence in bilingual Japanese-English children. Their experiments showed that 6-year-old Japanese-English bilingual children were more advanced in their scalar implicature interpretation in Japanese than their Japanese monolingual peers. All their experiments showed that bilingual children in different languages better understood pragmatic implicature interpretations than their monolingual peers.

On the other hand, Dupuy et al. (2018) showed mixed results in studying adult native speakers of French and L2 learners of either Spanish or English in scalar implicature reading. French speakers who were Spanish and English L2 learners showed better performance in pragmatic interpretation than French monolingual peers, p < 0.05, but no differences between the L2 languages, p > 0.05. Comparing between English and Spanish L2 learners, they showed no differences in their pragmatic interpretations, p > 0.05. Furthermore, in their experiment, studying whether there is a genuine increase of pragmatic abilities when learning an L2 language, under a between-subjects design, L2 learner did not show better performance than the French monolingual peers, p > 0.05.

Syrett et al. (2017) also found that children and young adult Spanish-English bilinguals in NJ, USA, performed well in their pragmatic interpretation tasks in Spanish. However, they did not find a bilingual advantage in scalar implicature reading in contrast to other experimental findings (Siegal et al., 2010, 2009, 2007). Even more Syrett et al. (2017, p. 16) argue that bilingual children may face even more significant difficulties in “successfully distinguish specific lexical entries from each other (language)”. According to Syrett et al. (2017) these difficulties are compensated as children grow and proficiency in their language(s) increases.

The experimental results analyzed here show us that there is no clear consensus of whether or not bilingual speakers have cognitive advantages in pragmatic reading. In order to grasp linguistic and extra-linguistic factors that can influence pragmatic reading, Antoniou and Katsos (2017) used vocabulary tests such as the Word Finding Expressive Vocabulary Test and the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) test. They also performed the Alberta Language Environment Question (ALEQ), (Paradis, 2011), the Alberta Language Development Questionnaire (ALDeQ) (Paradis et al., 2015). The Socio-Economic-Status (SES) variables measured for their experiment showed no correlation in pragmatic interpretation. Antoniou and Katsos (2017) found that age was a significant predictor of pragmatic interpretation in multilingual groups but not for monolinguals. Their findings suggest that other “non-linguistic factors, besides Executive Components (EC), that develop with age are possibly involved in and sustain the process of computing implicatures in multilinguals,” but failed to mention what they are.

The current research endeavor investigates the potential influence of sociolinguistic and extra-linguistic factors, including education level, Language Use, L1 proficiency, computer access, and internet access can have an impact on the pragmatic interpretation of the Kichwa quantifier wakin in Imbabura Kichwa. All these variables were captured using the ALEQ-3 questionnaire Soto-Corominas et al. (2020) adapted to the Imbabura Kichwa context. Drawing upon prior studies conducted in bilingual populations, there is no conclusive evidence to suggest that bilingualism confers any benefits or advantages in tasks involving pragmatic interpretation. The current research project was conducted within a Kichwa-Spanish bilingual context. Consequently, it is anticipated that bilingualism may exert some influence on our findings. Our results could shed further light on whether bilingualism confers an advantage in pragmatic interpretation within the Kichwa-Spanish bilingual context.

1.6 Kichwa quantifier wakinImbabura Kichwa quantifiers are tukuy = all, wakin =some and tawka = many. Negative quantifiers are mana ima shortened to nima = none or nothing as influenced by Spanish contact with an insertion of the Spanish negative conjuction ni meaning “not even”. For Southern Quechua, Muysken (1992) and Faller and Hastings (2008) give some details of the properties of the Quechua quantifiers:

(a) Quantifiers, morphologically nouns, can be inflected for person and number.

(b) Quantifiers may be “floated away” from the element they modify.

(c) Quantifiers differ in the extent to which they trigger subject or object agreement on the verb.

Muysken (1992) also noted that Southern Quechua quantifiers carry inflectional markers. He states that there are three different forms to be distinguished: (a) obligatory inflection, (b) optional inflection, and (c) no inflection. He argues that the indefinite quantifier wakin “can, but need not carry person marking.” In many dialects of Quechua, wakin is an obligatorily inflected quantifier. Faller and Hastings (2008) argue that while “quantifiers can occur prenominally, they often also occur without a head noun” in Quechua. They also classiffy wakin as a strong quantifier among the other Quechua quantifiers. Faller and Hastings (2008) use these terms in a purely descriptive manner, arguing that weak quantifiers can occur in existential sentences, and strong ones are those excluded from this environment. Sentences (8) to (11) show the possible scenarios where wakin may occur in Imbabura Kichwa.

(8) Wakin runa-kuna ri-naku-n

some people-PL go-PL.PROG-3

Some people are going xlist

(9) *Wakin-kuna runa-kuna ri-naku-n

*some-PL people-PL go-PL.PROG-3

*Some people are going xlist

(10) Wakin-kuna ∅ ri-naku-n

some-PL ∅ go-PL.PROG-3

Some (people) are going xlist

(11) Wakin ∅ ri-naku-n

some ∅ go-PL.PROG-3

Some (people) are going

In example (8), wakin stands alone with no inflectional morphemes attached. In the case of Imbabura Kichwa, this is the canonical form where wakin occurs, and this is the form used for the experimental process in this study. Moving forward, example (9) does not allow double inflection, turning the example ungrammatical. Imbabura Kichwa does not allow double plural marking at the NP node.

Example (10) is grammatical even though it does not have the head noun. In this example, we presuppose that the object we refer to (people) exists in the discourse and was previously introduced to the audience. Incorporating a noun into sentence (10) renders the sentence ungrammatical.

In (11), the plural marker -kuna, is not required as in wakin rinakun, meaning (some (people) are going); wakin already gives the reading of more than one interpretation. According to Faller and Hastings (2008) and Muysken (1992), wakin is presupositional, already discussed in sentences (10) and (11). Faller and Hastings (2008) argue that “wakin-quantified noun phrases are felicitous only in contexts where the non-emptiness of the restriction is presupposed.” The previous statement assumes that the elements (plural) are known to the speakers, and they are aware of it, as we explained in sentences (10) and (11). To support this claim, Faller and Hastings give an example for Cuzco Quechua in (12) and (13) below, where wakin can be optional, and is simply understood conversationally as some:

(12) Tari-sqa-ku-raq (wakin) dodo-kuna-ta

find-NX.PST-PL-CONT some dodo-PL-ACC

“ They found (some) dodos.”

(13) Wakin loro-kuna rima-nku

some parrot-PL talk-3PL

“Some parrots talk” (and others are presumed not to talk)

The provided examples, particularly example (12) offer compelling evidence that the inflection of the indefinite quantifier wakin in Cuzco Quechua is optional and context-dependent. This is consistent with wakin's property as an indefinite yet proportional quantifier. Faller and Hastings (2008) state that wakin “is therefore more similar to the English stressed SOME than the partitive some of (the).”

To this point, no experimental studies have been conducted on pragmatic interpretation in Indigenous languages, as previously discussed. Consequently, this paper aims to experimentally ascertain whether the Imbabura Kichwa quantifier wakin permits the pragmatic scalar interpretation of “wakin, mana tukuy = some, but not all,” as observed in other languages. To address this query, this paper presents a discussion of the four experiments executed for this purpose. Each experimental unit is unique, and as a result, the research questions are provided prior to each experimental procedure, and the analysis of the results is given after each experiment. This approach guarantees a comprehensive understanding and seamless flow between each experiment and permits a methodical evaluation of each one. This strategy reinforces the consistency of the paper and promotes a structured examination of each experiment.

2 Experiment 1Imbabura Kichwa (as well as the Ecuadorean Kichwa language family) does not strongly prefer stress-accented solid forms in the language (Lombeida-Naranjo, 1976; Cole, 1982). However, as a native speaker of Imbabura Kichwa, I have experienced the use of stress to emphasize the topic being discussed in a casual conversation. As in English, I consider that there is an accented form of the Kichwa quantifier wakin that delivers the “some, but not all” pragmatic interpretation. Following Faller and Hastings (2008)' statement that Kichwa's wakin is similar to the pitch-accented SOME in English, I aim to investigate the following research questions.

1. Do Kichwa speakers recognize two variants of the quantifier wakin: the canonically accented [ˈwa.kiŋ] and the final syllable accented form [wa.ˈkiŋ]?

2. Do Imbabura Kichwa-Spanish bilingual adult speakers generate the “wakin, mana tukuy = some, but not all” pragmatic interpretation with the Kichwa existential quantifier wakin under the Truth Value Judgement Task using the explicit Question Under Discussion paradigms with either variant of wakin?

2.1 ParticipantsFor this first experiment, a total N = 18 adult Kichwa-Spanish bilingual speakers from the indigenous communities of Gualapuro in Otavalo and El Cercado in Cotacachi were selected—participants who did not pass the fillers (N = 6) were not included for statistical procedures. A total of 12 participants (M = 35.5 years, SDev = 13.7 years, Range: 19.4–58.4 years) who passed the fillers stimuli were selected for statistic measures. All our participants in this experiment were early sequential bilinguals (Amengual, 2019), they were exposed to Kichwa at birth and learned Spanish at school or later in life.

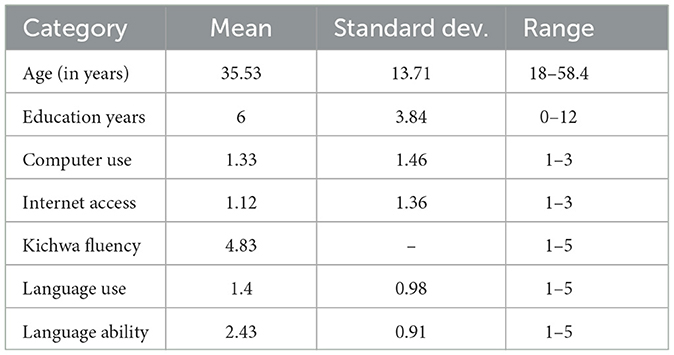

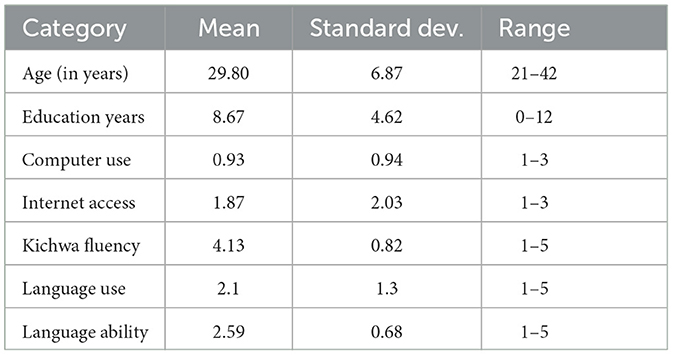

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for sociolinguistic variables from the ALEQ questionnaire.

Table 2. ALEQ results.

All ALEQ-3 (Soto-Corominas et al., 2020) variable averages come from participants' self-reported data. The results from the ALEQ-3 questionnaire show us that participants in this first experiment were older than any of the participants in previous pragmatic experiments regarding quantifiers (Dupuy et al., 2018; Siegal et al., 2010, 2009; Syrett et al., 2017; Pratt et al., 2018; Janssens et al., 2014). We also observe that the Education Years (M = 6 years) are very low compared to adult participants in other language experiments. We measured other sociolinguistic variables like Computer Use. The scores were computed as follows: 1 = no Computer Use; 2 = sometimes; 3 = always, averaging 1.3 (see Table 2). This means that the average participants in this experiment do not know how to use a computer. Also, using the same scale (1–3), results showed that most of our participants did not have Internet access in their homes.

When talking about Fluency in Kichwa, the results (M = 4.83, Range 1–5) show us that they are completely fluent in the language. They use the language in most of their daily communication with others in rural areas.

Language Use was measured by asking which language participants used the most with their close and extended family members. Scores were given according to this criterion: Only Kichwa = 1; More Kichwa Less Spanish = 2; Equal Kichwa and Spanish = 3, More Spanish Less Kichwa = 4, Only Spanish = 5. Results for Language Use show us that our participants were communicating almost all the time in Kichwa (M = 1.4).

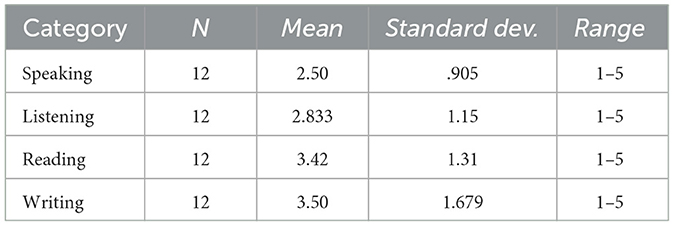

We also measured the Language Ability of the participants. Participants self-reported their ability to read, write, listen, and understand both languages, Kichwa and Spanish, using the following scale: Only Kichwa = 1; More Kichwa Less Spanish = 2; Equal Kichwa and Spanish = 3; More Spanish Less Kichwa = 4; Only Spanish = 5. Overall, the results from Table 2 show us that participants are more or less balanced bilinguals leaning toward Kichwa dominance (M = 2.43, Range = 1–5). However, Kichwa is not taught in schools (Conejo, 2008; Haboud, 1998) but rather is orally transmitted. Consequently, we needed to analyze this data more closely (see Table 3).

Table 3. Language ability.

We performed a paired t-test comparing the means for these variables. The Speaking-Listening paired t-test showed no difference in scores among them, [t(11) = −1.483, p = 0.166]. Similarly, there was no difference in scores among the Reading and Writing variables, paired t-test, [t(11) = −0.290, p = 0.777]. There are significant differences in scores between Speaking and Reading, [t(11) = −4.750, p = 0.001]; Speaking and Writing, [t(11) = −25.71, p = 0.02]; Listening and Reading, [t_(11) = −3.02, p = 0.12], and no significant differences in Listening and Writing, [t(11) = −2.00, p = 0.07]. We think these results are valuable for understanding Kichwa's situation as a traditionally oral language.

Performing a co-linearity test, the variables Access to the Internet (VIF = 5.33) and Computer Use (VIF = 7.37) showed high co-linearity effects for the Education Years variable. Therefore, the Computer Use variable was chosen for the statistical calculations.

2.2 ProceduresThe stimuli discourse units used for this experiment were translations of the Spanish version used in Mexico City by Grinstead et al. (2010) to the Kichwa language. Four warm-ups, four fillers, and ten experimental sentences were developed under the criteria of Question Under Discussion (QUD) conversational discourse (Roberts, 2003). For the experimental stimuli, ten discourse sentences were created for each phonetic variant, [ˈwa.kiŋ] and [wa.ˈkiŋ]. They were created and assembled in “3 out of 4” and “4 out of 4” contexts of the stimuli. These contexts were set in the idea that “3 out of 4” and “4 out of 4” cartoon characters are performing an action in a motion-animated audio and video scenario.

2.3 StimuliFor this experiment, we used a variation of the traditional TVJT in Mexican Spanish, as first implemented by Grinstead et al. (2019). The audio content was later translated into Kichwa and recorded by a Kichwa-Spanish-English tri-lingual female speaker using Audacity v.2.4.1 directly into a personal computer, which allowed experimenters to control some aspects of the context, including Prosody, Conversational Common Ground (CCG), and Question Under Discussion (QUD). The reader was a native speaker of Imbabura Kichwa and a native speaker of Highland Ecuadorean Spanish. Here is one of the experimental stimuli examples.

(14) Wawa-kuna-ka wasi-pi-mi television-ta riku-nkapak

chakana-ta witsiya-nkapak muna-n.

child-PL-TOP house-LOC-AFF tv-ACC watch-COREF ladder-ACC climb- COREF want-INF-PROG.

“The children want to climb the ladder to go watch TV.”

Sentence (14) creates a background information that sets the stage for the upcoming QUD scenario. The following sentence (15) gives more detailed information about the activity these cartoon characters are about to perform.

(15) Uh chakana-ka yapa hatun-mari mana tukuy-lla

witsiya-y ushan-ka-chu yani-mi.

Uh-Oh ladder-TOP much high-EMPH-witness NEG all-LIM climb-IMP can-3FUT-DUB think-VAL

“Uh-Oh! The ladder is too high, I don't think all the children will be able to climb it.”

Here in (16), we have the explicit Question Under Discussion scenario which prepares participants for the YES/NO answer to the upcoming question.

(16) Pikuna-shi witsiya-nka chakana-ta?

who-PL-REP climb-3FUT ladder-ACC-TOP.QUESTION

“Who is going to climb the ladder?”

This sentence (17) contains our target quantifier, in which participants are expected to answer YES to the “3 out of 4” context and reject the “4 out of 4 context” for all the experimental stimuli for both of the forms of the quantifier wakin.

(17) Ahh ña yacha-ni [ˈwa.kiŋ/wa.ˈkiŋ] wawa-kuna

witsiya-rka chakana-ta

well now know-1 some child-PL climb-PAST ladder-ACC

“Well, I know. Some children were able to climb the ladder”

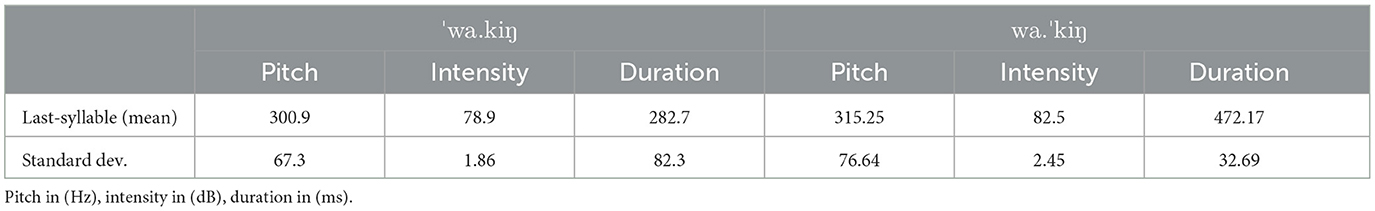

The speaker was instructed to pronounce wakin as [ˈwa.kiŋ] and [wa.ˈkiŋ] for each stimuli. These audio recordings were then analyzed for pitch, duration, and intensity for both [ˈwa.kiŋ] and [wa.ˈkiŋ] at the last syllable using the Praat v.6.0.4 software. Table 4 shows the results of these measurements.

Table 4. Phonetic variants of wakin.

Running the R software, the One-way ANOVA test found that pitch on the final syllable was not significantly different for the two forms of wakin [F(1, 18) = 0.60, p = 0.66]. For intensity, the One-Way ANOVA test showed an effect on the final syllable intensity on quantifiers [F(1, 18) = 13.4, p = 0.002]. The same One-Way ANOVA test showed an effect of final syllable duration on the quantifiers [F(1, 18) = 45.69, p < 0.001]. For this experiment, we created two forms of the quantifier, [ˈwa.kiŋ] and [wa.ˈkiŋ] which differed in Duration and Intensity but not pitch. These stimuli and the warm-ups and fillers were encoded in the SuperLab v5 software. The four warm-up stimuli were placed at the beginning of the trials to familiarize participants with the upcoming experimental work. The experimental and filler stimuli were placed in a random order. Participants were distributed evenly under the between-subjects experimental design in which the subjects are assigned to different conditions.

Before starting the experiments, all participants were asked to complete the adolescents (adult) version of the Alberta Language Evaluation Questionnaire (ALEQ) by Soto-Corominas et al. (2020). Only filler passer's ALEQ results are included for statistical measures.

For the experimental part, participants were asked to press the C key in the keyboard which was labeled with a happy face  if they agree with the statement or press the M key labeled with a sad face

if they agree with the statement or press the M key labeled with a sad face  if they disagree with the statement.

if they disagree with the statement.

Reaction Time (RT) (in milliseconds = ms) was also calculated following this criterion. The duration (in ms) from the beginning of the stimuli up to the beginning of the quantifier pronunciation was calculated. This time was called Time Before Quantifier (TBQ). A second measurement was also calculated from the beginning of the audio stimuli until the participants pushed the key, called End Point Time EPT. Then, using simple mathematical operations, the RT was calculated as the difference of EPT−TBQ.

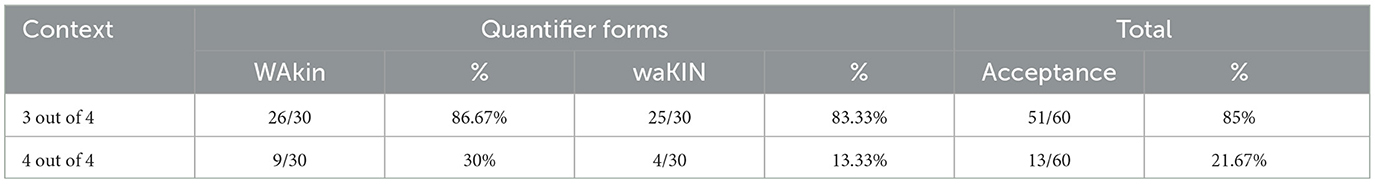

2.4 Results 2.4.1 Descriptive statisticsIn the following table, we have the means for acceptance for the 3 out of 4 and 4 out of 4 contexts for both forms [ˈwa.kiŋ] and [wa.ˈkiŋ] of the Kichwa quantifier wakin. A total of N = 6 participants, three for each phonetic variant of wakin, were discarded from the sample. These participants failed to answer correctly the filler stimuli (see Table 5).

Table 5. Acceptance rate by quantifier form.

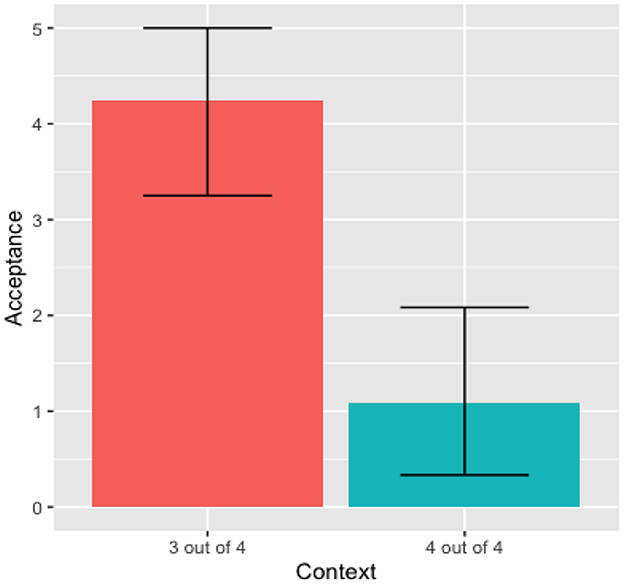

2.4.2 Inferential statisticsIn calculating the inferential statistics, we use the R version 1.3.959 software. The two-way ANOVA test, considering Context as a function of Acceptance and the Phonetic Forms of the quantifier, showed no significant effect of the phonetic forms in the Acceptance rate [F(1, 21) = 0.29, p = 0.60]. Looking into each context, the One-way ANOVA test for the “4 out of 4” context, show no significant effects of the two phonetic forms in the Acceptance rate, [F(1, 10) = 0.776, p = 0.399]. Similarly, the One-way ANOVA test for the “3 out of 4” context shows no significant effects of the phonetic forms in the Acceptance rate [F(1, 10) = 0.03, p = 0.867]. These results show that Kichwa speakers do not recognize different phonetic variants for the quantifier wakin for the tested phonetic variables (intensity, pitch, and duration). Thus, there was no difference between quantifier variants nor between contexts. Consequently, this data was condensed into a single distribution for the quantifier wakin, as observed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Adults' mean acceptance wakin (condensed).

Our focus was on the rejection rate of the “4 out of 4” context, because that rejection generates the “some, but not all” pragmatic interpretation. The One-way Anova test for the condensed data showed a significant effect of the context [F(1, 22) = 23.16, p < 8.3e-05]. Based on the data from Figure 1, we can infer that Kichwa participants did generate the “some, but not all” pragmatic reading. The percentage of rejection of the “4 out of 4” was 78.33% (47/60).

We found that Language Ability (measured on a scale of 1–5, the ability to speak, read, write, and listen in Kichwa or Spanish, where 1 = Kichwa, 5 = Spanish) positively correlates with Acceptance. Performing the simple linear model (lm) test, the Language Ability variable showed a significant impact on Acceptance, (r2 = 0.362, B = 1.033, SE = 0.434, p = 0.039). These results show that Spanish-leaning participants performed better in the task. Their higher bilingual ability gave them the advantage of performing better in this experimental task.

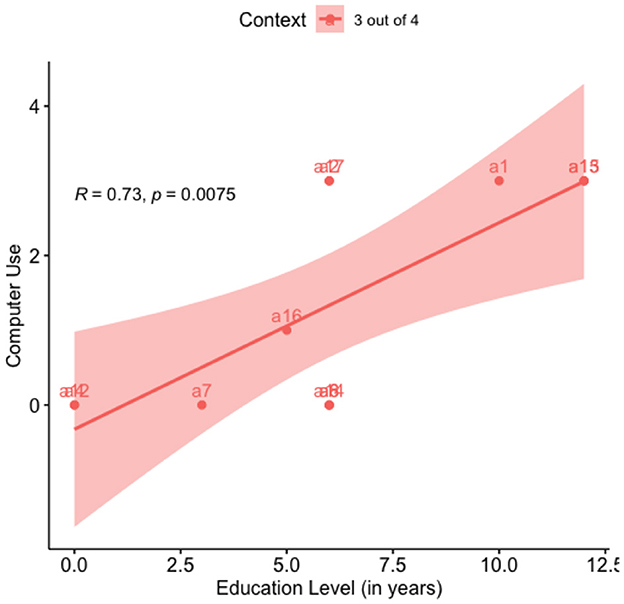

As mentioned earlier in this section, Computer Use correlates positively with Education Years. Education Years significantly impact Computer Use, (r2 = 0.527, B = 1.91, SE = 0.571, p = 0.0075), which is expected as more educated individuals have more access to computers. This relationship is shown graphically in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Regression: acceptance vs. education level.

2.5 Discussion experiment 1Answering the first research question (i), our results showed that adult Kichwa speakers do not recognize two phonetic variants for the quantifier wakin, as we initially hypothesized. Even though we could show both versions of wakin successfully, speakers could not assign them different pragmatic readings. In that sense, the claim made by Faller and Hastings (2008, 308), where they state that “wakin is therefore more similar to English stressed SOME than the partitive some of (the)” seems to not apply to Imbabura Kichwa's wakin, at least insofar as it concerns phonetic form, and not meaning.

Our first research question (i) concerned the effect of the phonetic variant in pragmatic reading and the generation of the “some, but not all” interpretation. We were expecting that the final syllable stressed form [wa.ˈkiŋ] (in line with the first research question) would yield a “some, but not all” pragmatic reading more categorically than [ˈwa.kiŋ], similar to the English stressed form SOME (Grinstead et al., 2010; Thorward, 2009). That was not the case. There is only one form of the quantifier pronounced [ˈwa.kiŋ].

For our second research question (ii), adult Kichwa speakers could generate a “some, but not all” pragmatic interpretation in this experiment to some degree. Even though we got a 78.33% rejection of the “4 out of 4” context, these results are similar to the rates found for some of the experiments in other languages. (Janssens et al., 2014; Thorward, 2009; Vargas-Tokuda et al., 2009; Papafragou and Musolino, 2003; Noveck, 2001). Though, these results are not as categorical as in Pratt et al. (2018).

Our results also found that participants' years of education played a fundamental role in Acceptance rates. The inferential statistics showed a significant effect of Education in Acceptance for the “3 out of 4” context. Even more, we saw that the education variable strongly affected reaction time and Computer Use. As expected, the more educated individuals delivered the tasks faster than those with less education. Similarly, the more educated the individuals were, the more familiar they were with computers. We observe that this may be the cause as to why we did not get the expected highest acceptance rates in this experiment.

3 Experiment 2The Kichwa results were not as categorical as expected. We considered this to be due to some intrinsic properties of the Kichwa quantifier wakin. To eliminate this probability of whether this is a Kichwa-intrinsic issue, we followed this up by testing Spanish monolingual and bilingual Kichwa-Spanish speakers' interpretation of the corresponding Spanish existential algunos to determine whether there might be some type of language contact distinction rooted in Kichwa causing the less categorical responses. That is, if there were some sort of general inclination rooted in Kichwa not to accept existential quantifiers in universal contexts, we might find an influence of it in the use of the analogous Spanish existential algunos.

1. Do Ecuadorean monolingual Spanish-speaking adults from different social backgrounds generate the “algunos, pero no todos = some, but not all” pragmatic implicature reading with the Spanish existential quantifier algunos?

2. Do Imbabura Kichwa-Spanish bilingual adults from different social backgrounds generate the “algunos, pero no todos = some, but not all” pragmatic implicature reading with the Spanish existential quantifier algunos?

3.1 ParticipantsThis second experiment consisted of two different groups. A total of N = 20 adult Kichwa-Spanish bilinguals from rural Kichwa communities around Cotacachi and Otavalo participated in this experiment. They were different participants from the first experiment. Participants who did not pass the fillers (N = 5) were excluded from the data. A total of 15 participants (M = 29.8 years, SDev = 6.87 years, Range = 21–42 years) passed the fillers. Kichwa-Spanish bilingual participants in this experiment also filled out the Alberta Language Evaluation Questionnaire (ALEQ-3) by Soto-Corominas et al. (2020) to study whether sociolinguistic and extralinguistic factors are influencing or not the implicature reading in this population. These bilingual participants were also early sequential bilinguals as in our first experiment (Amengual, 2019, p. 956), they were exposed to Kichwa at birth and learned Spanish at school or later in life. The second group consisted of 20 adult Spanish monolingual speakers from Cotacachi, Imbabura. None of them were ethnically Kichwa individuals. A total of N = 18 participants passed the fillers (M = 31.50 years, SDev = 8.89 years, Range: 18–38 years). The monolingual participants of this experiment, even though they lived in Kichwa-speaking areas, did not speak a single word in Kichwa, nor had contact with other languages.

Table 6 shows the descriptive data for sociolinguistic variables from the ALEQ questionnaire for the Kichwa-Spanish bilingual participants.

Table 6. Sociolinguistic variables data.

3.2 ProceduresThe stimuli discourse units used for this experiment were the Spanish version used in Mexico City by Grinstead et al. (2010). Similar to experiment 1, there were four warm-up sentences, four filler sentences and ten experimental sentences following the criteria of Question Under Discussion conversational discourse (Roberts, 2003). For the experimental stimuli, five (5) discourse sentences for algunos were created. They were used in both “3 out of 4” and “4 out of 4” contexts. By context, we mean that for each contexts, “3 out of 4” and “4 out of 4” cartoon characters are performing an action in a motion-animated audio and video scenario under the QUD paradigm.

3.3 StimuliFor this experiment, we used a variation on the traditional TVJT, as first implemented by Grinstead et al. (2019). The audio content was adapted to the Ecuadorean Highland (Quiteño) Spanish variety. We recorded the audio directly into a personal computer via Audacity v.2.4.1. Recordings were made by the same Kichwa-Spanish-English trilingual female who recorded the Kichwa stimuli. No further changes were made. Here is one of the experimental stimuli examples.

(18) Los niño-s está-n en la casa. Quiere-n subir a ver la

tele.

The.PL child.PL Be-3PL in the house. Want-3PL climb to watch the television.

“The children are at home. They want to climb the ladder to go watch TV.”

Sentence (18) creates background information to set the stage for the upcoming scenario. The following sentence (19) gives more detailed information about the activity these cartoon characters are about to perform.

(19) Oh no! Las escalera-s son muy alta-s.

Uh-Oh the.PL ladder-PL be.PL very high.PL

“Uh-Oh! the ladder is too high.”

This is followed by the explicit Question Under Discussion in (20), which prepares participants to affirm or reject the final experimental sentence.

(20) Quién-es va-n a subir las escalera-s?

who-PL go-3PL to climb the.PL ladder-PL

“Who is going to climb the ladder?”

This sentence (21) contains our target quantifier, in which participants are expected to answer YES to the “3 out of 4” context and reject the “4 out of 4” context for all the experimental stimuli for the quantifier algunos.

(21) Ya se, algunos niño-s subi-eron las escalera-s

I know. some child-PL climb-PAST.PL the.PL ladder-PL

“Well, I know. Some children were able to climb the ladder”

The stimuli, including the warm-ups and fillers, were encoded in the Superlab v5 software. The four warm-up stimuli were placed at the beginning of the trials to familiarize participants with the upcoming experimental work. The experiment and filler stimuli were placed in random order. We did a within-subjects experimental design in which language was the distinctive factor.

Before starting the experiments, Kichwa-Spanish bilingual participants were asked to complete the ALEQ-3 (Soto-Corominas et al., 2020) questionnaire to capture the sociolinguistic information. Only the ALEQ results of the fifteen participants who passed the fillers are included for statistical purposes. Spanish monolingual participants were not asked to fill out the ALEQ-3 questionnaire. For the experimental part, participants were asked to press the C key on the keyboard, labeled with a happy face  , if they agree with the statement, or press the M key, labeled with a sad face

, if they agree with the statement, or press the M key, labeled with a sad face  , if they disagree with the statement.

, if they disagree with the statement.

Table 7 shows the acceptance results for each context, “3 out of 4” and “4 out of 4” separated by each group or participants.

Comments (0)