The midface’s skin and mucosa are supplied by maxillary nerve, which is the second division of trigeminal nerve and gives rise to infraorbital nerve. It enters the face through infraorbital foramen and divides into three alveolar proximal branches (anterior, middle, and posterior superior alveolar nerves) and four distal branches (inferior palpebral, external nasal, internal nasal, and superior labial).[1-4] Soft tissues, canines, and incisors are all served by anterior superior alveolar (ASA) branch.[5] Another significant anatomical feature in premaxillary region is the nasopalatine canal. The nasopalatine arteries and nerves supply this region, distributing to the anterior teeth and soft tissues.[3] In this area, there are several auxiliary foramina that may be mistaken for apical diseases due to their variations in size and morphological characteristics.[6]

In 1939, Jones published the first account of canalis sinuosus (CS) as one of the area’s auxiliary canals. The name originated from the double curvature of the structure. In Jones’ original description, the CS is described as a neurovascular bundle that goes through a convoluted bony channel lateral to the nasal cavity, roughly 2 mm in diameter, and starts from posterior portion of the infraorbital foramen.[2] Its location and anatomical structure have been thoroughly documented by various other authors. Starting around 25 mm behind the infraorbital foramen, channel descends to the orbital floor, shifts medially to maxillary sinus anterior wall, and then continues to anterior nasal aperture. In canine region, dental plexus is formed by the neurovascular branches of CS. Inside the CS, the ASA nerve innervates canine and incisor areas as well as the surrounding soft tissues.[7-10]

Of all studies so far, 52.1–88% have the CS identified.[11-15] For this reason, a number of studies have proposed that the CS could be regarded as an anatomical structure as opposed to merely an anatomical variation.[8-14] However, even after 81 years of its initial description, dental practitioners’ still lack sufficient knowledge about the CS.[2] Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) is the method typically used to examine CS. Unlike helical computed tomography (CT), this method uses lower radiation doses while providing greater detail. In addition, CBCT allows for multiplanar image reconstruction, as well as linear and angular measurements, significantly reduces picture overlap.[16]

This research aims to evaluate and identify the position and diameter of the CS, accounting for variables such as age, gender, and distance from important structures such as the incisive foramen, nasal cavity floor, buccal cortical bone edge, and palatal cortical bone.

MATERIAL AND METHODS Data collectionCBCT images from 650 participants who satisfied the inclusion criteria were included in the current investigation. From the image files, the patients’ identities were deleted. The study’s inclusion criteria included CBCT scans from consenting patients and maxilla CBCT images of patients receiving implants. Exclusion criteria that were applied were as follows: (1) imaging artifacts that would make it difficult to evaluate important structures; (2) images with implants, grafted alveolar ridges, or missing teeth; (3) presence of additional or retained deciduous teeth in the anterior maxilla; (4) any pathological lesion in the anterior maxillary region; (5) patients who have undergone previous maxillary surgery, including orthognathic surgery; and (6) CBCT scans with poor acquisition quality in voxels larger than 0.20 mm within a 40-s examination window.

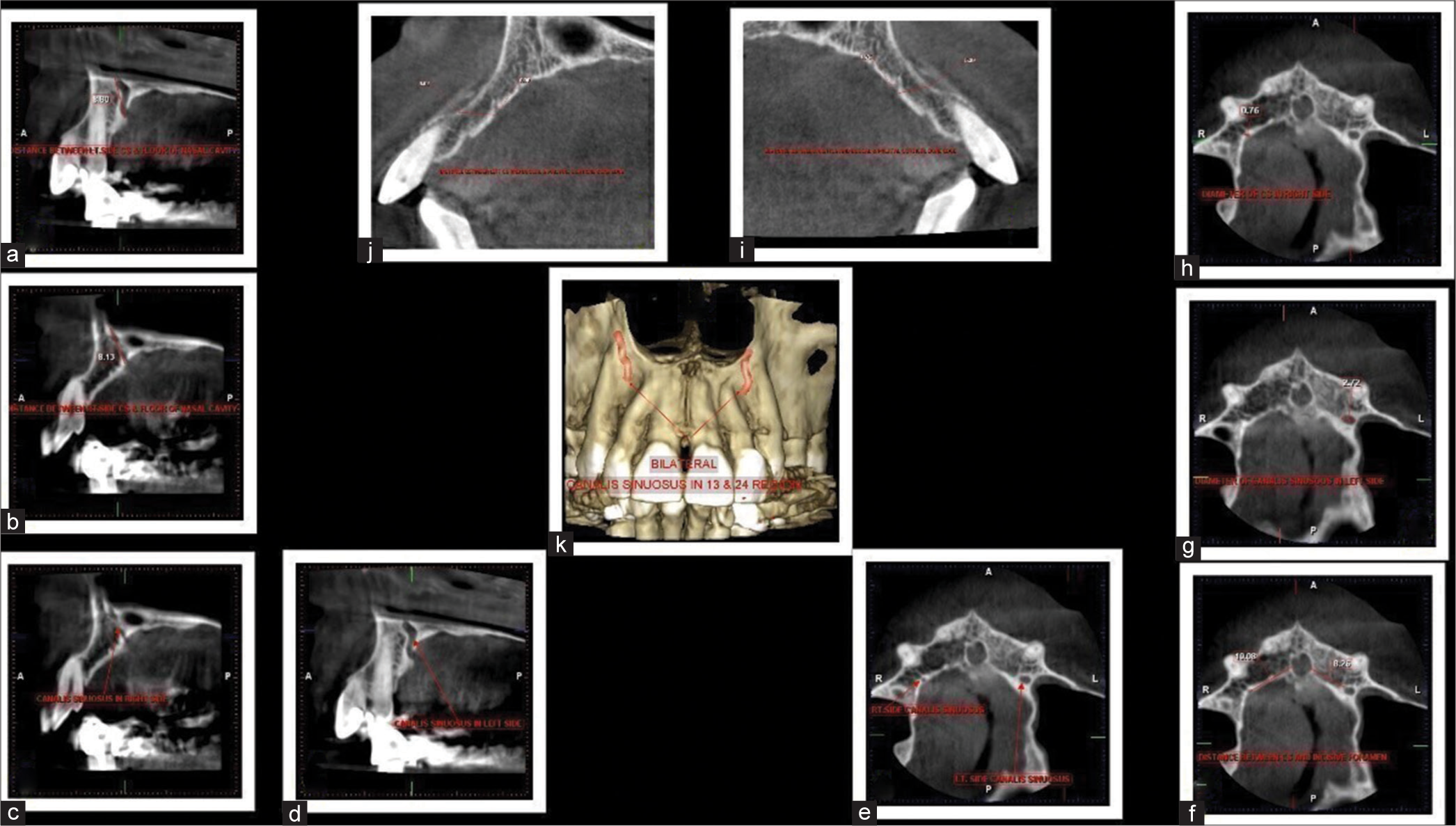

ProceduresAnatomical description of the CS, as found in the literature, was used to identify it on the CBCT images. Bony canals were found in the anterior maxilla and were observed to point clearly upward toward the CS. The assessed parameters taken into account includes: either the presence or absence of the CS, diameter, position, distance between CS and nasal cavity floor, incisive foramen, buccal cortical bone edge, and palatal cortical bone in relation to age and gender. The diameter of each canal was measured halfway along its course, which is the distance from its beginning at the CS to its terminus. Figure 1 displays the morphometrics of the CS. The reconstructions of the axial, coronal, sagittal, panoramic, and cross-sectional views were examined for each instance. Measurements of the palatine aperture on coronal and cross-sectional images of the extra canal were used to calculate diameters. Two evaluations of CS locations were performed by the same observer, at least 2 months apart.

Export to PPT

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics are used to analyze the data. To evaluate differences for various parameters among males and females, the χ2 test and Student’s t-test were employed. Depending on whether the data were normal, Mann–Whitney test was additionally applied where necessary. To ascertain the relationship between quantity of CS and sex, Spearman’s correlation was employed. The association between age and other two additional variables such as the diameter of CS and number of CS was evaluated using Pearson’s correlation and linear regression. Using Cohen’s kappa, intraobserver agreement for categorical data was assessed. An established threshold for significance was set at P < 0.05. Version 20.0 of IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to analyze all of the data.

RESULTSThe study comprised 650 patients with a mean age of 42.19. Males were the predominant gender with a count of 349, while females had a count of 301. Figures 2-4 represent the gender presentation, presence of CS, and its laterality. In Table 1, the ages of the subjects in the CS groups (present/absent) were compared. The CS present group’s mean age was marginally higher than the other groups, with P = 0.0032 indicating a statistically significant difference in mean age between two groups. Similarly, the gender of the subjects was compared between the groups. It was found presence of canalis sinuous in 59% males and 48 % females. CS was absent in 40% males and 51 % females. This indicates an association between the two variables (gender and CS) with P = 0.003.

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Table 1: Descriptive statistics for presence of canalis sinuosus.

Parameters Canalis sinuosus P-value Present n(%) n=354 Absent n(%) n=296 Age in years: Mean (SD) 43.81 (15.46) 40.27 (17.69) 0.0032M (S) Gender Male 209 (59.89) 140 (40.11) 0.003C (S) Female 145 (48.17) 156 (51.83)The right and left sides were compared with respect to a number of parameters, including CS diameter, distance between it and floor of the nasal cavity, incisive foramen, edges of the buccal cortical bone, and palatal cortical bone. There was no discernible difference in the mean distances of these metrics on the left and right sides [Tables 2 and 3]. Parameters such as the distance between the CS and nasal cavity floor, incisive foramen, buccal cortical bony edges, palatal cortical bone, and the diameter of the CS were compared between males and females for both right and left sides. Results showed that the diameter of the right side CS and distance between it and the nasal cavity floor, along with the margin of buccalpalatal cortical bone, were statistically significant for both genders. Significant for both genders were the nasal cavity floor and buccal cortical margins on the left side [Table 4].

Table 2: Position of canalis sinuosus distribution.

Position Laterality Right side n (%) Left side n(%) Bilateral n(%) In central incisor region 5 (13.89) 13 (16.67) 96 (20) Between central incisor and lateral incisor 8 (22.22) 9 (11.54) 73 (15.2) Lateral incisor region 7 (19.44) 24 (30.77) 174 (36.2) Between lateral incisor and canine 1 (2.78) 2 (2.56) 10 (2.1) Canine region 6 (16.67) 10 (12.82) 36 (7.5) First premolar region 2 (5.56) 4 (5.13) 16 (3.33) Lateral to incisive foramen 3 (8.33) 3 (3.85) 13 (2.7) Anterior to incisive foramen 4 (11.11) 13 (16.67) 62 (12.9) Total 36 (100) 78 (100) 480 (100)*Table 3: Comparison of various measurements on the right and left sides.

Distance Right sideTable 4: Comparison of various measurements for gender.

Distance Male Female P-value Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Right side n=171 n=105 Nasal cavity floor 16.49 (3.05) 14.83 (3.01) <0.0001T Incisive foramen 4.07 (2.93) 4.13 (3.08) 0.8704M Buccal cortical bone edge 8.06 (1.87) 7.41 (1.58) 0.0021M Palatal cortical bone edge 2.8 (1.54) 2.25 (1.61) 0.0454M Diameter of CS 0.82 (0.22) 0.78 (0.18) 0.0314M Left side n=191 n=127 Nasal cavity floor 17.05 (3.36) 15.07 (2.91) <0.0001T Incisive foramen 4.47 (3.24) 3.91 (2.76) 0.1872M Buccal cortical bone edge 8.13 (1.81) 7.65 (1.67) 0.0034M Palatal cortical bone edge 2.16 (1.33) 2.1 (1.32) 0.4964M Diameter of CS 0.83 (0.26) 0.84 (0.26) 0.5662MIn Figures 5 and 6, the different parameters such as distance between CS and nasal cavity floor, incisive foramen, buccal cortical bony edges, palatal cortical bone, and the diameter of CS are compared between the right and left sides for each gender. With P < 0.05, there was a significant mean difference in the diameter of CS between the right and left sides of females. However, none of the other factors show any significant changes (P > 0.05). Figure 7 compared gender of the patients with the laterality of the CS and found an association between the two variables. This association was statistically proven with P < 0.05.

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

DISCUSSIONClinicians’ awareness of anatomical variances improves prognosis and reduces the likelihood of complications.[5] The anterior maxilla contains significant neurovascular bundles. Surgical procedures may result in injury to these structures, leading to hemorrhaging; and sensory abnormalities (such as hyperesthesia, paresthesia, or discomfort). These injuries can appear as lesions, which may leads to diagnostic confusion, which was once reported by Shah et al. explaining the incorrect diagnosis of an accessory branch of the CS on periapical radiography as external root resorption.[6] It can be difficult to visualize the auxiliary branches of the CS using conventional radiography techniques, as these accessory canals often have a diameter of <1 mm. Moreover, the irregular course and porous cortical layers of the CS have been identified as a diagnostic challenge for traditional radiography techniques. In clinical practice, the variations of the CS and its auxiliary canals are not well-known. However, with the increasing use of 3D imaging in clinical practice, these variations are getting attention.

Out of 650 patients, CS was found to be more common in males (59.89%) than females (48.17%). Older age groups showed a higher prevalence of CS (15.46 %) compared to other groups. The results of a study by Machado et al.,[13] which also found a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of CS with male dominance, are consistent with these findings.

Manhaes Junior et al.[16] showed prevalence of 5% CS which is very low when compared to 54% found in our study. This could be due to various ethnic populations found in different parts of the country. In our investigation, CS had an average diameter of <1 mm. The mean distances of CS to various parameters were not substantially different on the left and right sides (P > 0.05). In addition, the study looked at gender-stratified distances between CS and other anatomical landmarks on both sides. For both males and females, there was statistical significance in the distance measured between CS and nasal cavity floor, diameter of CS on the right side, and margins of buccal-palatal cortical bone. For both genders, the nasal cavity floor and buccal cortical margin were substantial on the left side.

Manhaes Junior et al.[16] measured the distance between CS and anterior ridge crest (ARC), buccal cortical bone (BCB), and nasal cavity floor (NCF) at each study site and reported that, left-only distance determined by CS and BCB in female group differed significantly.

For every measurement, there were no differences between sides in male group. The CS-to-ARC and BCB distances were comparatively dissimilar, with a leftward bias in the mixed group. The lengths from CS to NCF on the right and left sides did not differ significantly in any groups.[17,18] When these parameters were compared separately in each gender, no statistical differences were found. Correlations were made between age and various measurements, but no significant correlation was found between any of the parameters and with age (P > 0.05). This finding is consistent with the previous studies by de Oliveira-Santos et al. and von Arx and Lozanoff, which also did not find any appreciable differences in age or gender.[7,9] The subjects’ mean ages were found to be equal in both groups when their ages were compared to the laterality of the CS, and there was no difference between their means (P > 0.05).

Our study also examined the lateralization of CS based on gender distribution and found a significant association between the two variables. According to the latest investigation, bilateral lateralization of CS was the most prevalent (78%) whereas the study conducted by Velpula et al.[19] showed that only 9.5 % this could be attributed towards ethnic variations. A study by Wanzeler et al. found a significant variance in the lateralization of CS and gender. Furthermore, it was found that the placement of the CS on the left and right sides correlates with age. On the right side, there was a weak negative correlation and on the left, a weak positive association. These connections, however, did not reach any statistical significance (P > 0.05).[8,10] Surgeons contemplating interventions in locations where the CS is present should be cognizant of its presence to minimize the potential of iatrogenic damage to the patient. Acknowledging it as a component of their pre-surgical workup can prove beneficial for them. Well-established standards state that before performing radiological imaging, one must weigh the expected information to be obtained against the ionizing radiation.

The European Association of Osseointegration recommendations state that if a clinical examination and conventional radiography provides sufficient information, then CBCT and other further imaging is not required.[20] However, as noted in a recent publication by Shelley et al., the American Academy Of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology endorses CBCT imaging for evaluations of all implant sites.[21,22] Future advancements in CBCT technology, which are anticipated to lower radiation dosages, enhance computer algorithms, and enable smaller scan windows, may cause these conflicting improvements to converge. Considering this uncertainty, it is recommended that the anterior maxilla’s CBCT be accessible and that the CS be actively sought out and recognized for an appropriate planning. Clinicians should also consider the possibility of impingement on the CS in cases when surgical operations performed on the anterior maxillary regions result in unanticipated unfavorable effects.[20-22]

CONCLUSIONRegardless of age or gender, CS is a common anatomical structure which is relevant for surgery in the area due to its great occurrence. Recognizing these distinct anatomical variations may aid surgeons in avoiding nerve injury during surgery. In comparison to females, males had a statistically higher frequency of CS. The age distribution showed a statistically significant difference. Anterior maxillary, or palatal region, is the most common location for the end of the accessory canal trajectory. The age and number of CS, age and diameter of CS, and number of CS and sex were found to have very little correlations. With a 100% CBCT identification rate for the CS in the current investigation, CBCT is the recommended investigative method for precisely identifying the CS. Significant variations between the left- and right-sided scans were observed throughout the CS. This information could be useful to physicians planning treatments in the CS area, potentially reducing iatrogenic neurovascular problems.

Comments (0)