In this retrospective, case series study, we reviewed physical and electronic files of patients with spinal gunshot wounds treated by the spine trauma department between January 2001 and November 2016. We evaluated the CT scan of each patient for bone patterns and instability. We also reviewed the reports of shock unit doctors, intensive care doctors, and general surgeon notes, to determine reported associated lesions. Incomplete files and patients with no CT scan were excluded. We performed a statistical analysis to obtain the pattern and frequency of spinal and associated injuries using Epi Info ver. 7.2.0.1 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA).

This study was approved as in compliance with the ethical standards of the local research and ethics committee of the Mexican Social Security Institute (CLIS 2016-3401-62).

ResultsWe included the files of 54 patients, of which 48 (89%) were men and six (11 %) were women. The age range was 9–75 years, with a mean of 30±13 years. All patients were civilians and had received a low-velocity gunshot wound.

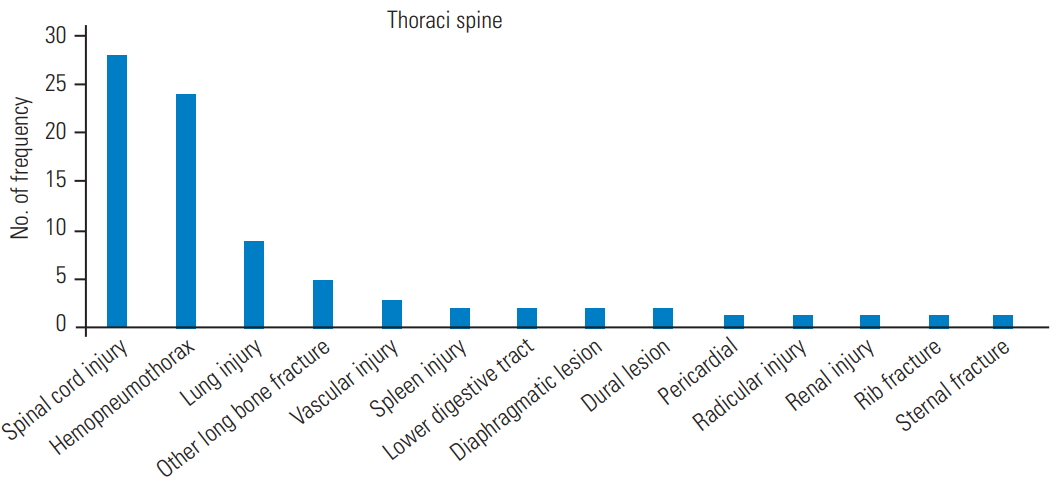

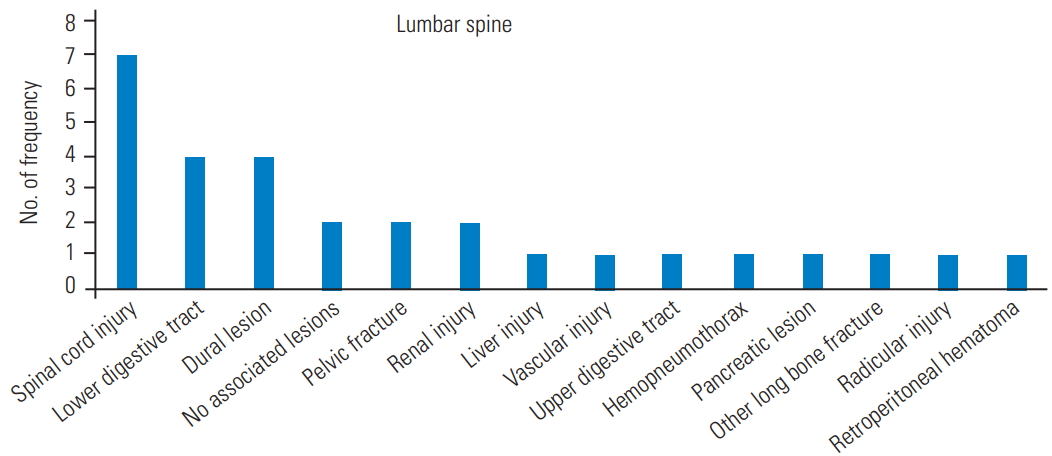

Of the 54 patients, 61% (33 patients) had complete SCI, 11 % (six patients) had incomplete SCI, and 27% (1 5patients) had no SCI, as shown in Table 1. The greatest spinal cord involvement was observed in the thoracic spine, as shown in Table 2. In the CT scan evaluation, we found eight different fracture patterns, shown in Table 3. These patterns were differentiated according to the part of the spine affected, including the disc. The most frequent pattern was the posterior arch (Fig. 1) , followed by a pure vertebral body (Fig. 2). The thoracic spine had the highest frequency of injury in our series. When we analyzed the associated lesions (Fig. 3), we found that the most frequently associated lesion was SCI (88%), followed by hemopneumothorax (75%), lung lesions (28%), and hepatic lesions (16%). The lumbar spine had the second highest frequency, with SCI being the most frequent (50%), followed by lower GI tract and dural tear at 29% each; other lesions are shown in Fig. 4. When we compared the spinal injury pattern with SCI, we found that all patients with posterior arch involvement with one or both pedicles and 86% of patients with vertebral body involvement and unilateral pedicle had an SCI, as shown in Table 4. When we considered the presence of pedicle fracture, with or without vertebral body or posterior arch involvement, 86% had an SCI, resulting in an odds ratio of 3.64 (95% confidence interval, 0.715–18.50) for severe SCI, with 11 Frankel A and 2 Frankel B grade injuries. The distribution of the spinal injury pattern related to SCI severity is shown in Table 5. Regarding patients with a vertebral body fracture and SCI as classified by spinal segment, eight injuries were in the thoracic spine and two were in the upper cervical spine, all of which had a Frankel A grade; the other two patients had injuries in the lumbar spine, of which one had a Frankel A and the other a Frankel B grade.In the upper cervical spine case (C2), a mandibular fracture along with a retrogastric hematoma was reported, and the lateral mass was injured. In the subaxial spine cases, a vascular injury was reported in three patients, one root lesion, three complete SCI, one with partial SCI and two cases had no associated lesion.

We evaluated the relationship between the spinal injury pattern and associated lesions. We found that, of the patients with no associated injury (four cases), one had an injured disc and three had a posterior arch fracture. The bone fracture pattern with the most associated lesions was the vertebral body, with a total of 19 lesions, followed by the posterior arch, with five lesions, as shown in Table 6.Of the hemopneumothorax cases, eight involved the posterior arch; six, the vertebral body; five, the vertebral body with unilateral pedicle; two, both pedicles and the posterior arch; two, the unilateral pedicle; one, the disc; and one, the unilateral pedicle with the posterior arch. Six patients had dural injury, of whom the vertebral body was involved in two patients; the rest had an involvement of the posterior arch with pedicles, posterior arch with unilateral pedicle, or unilateral pedicle with posterior arch. For radicular injuries, the posterior arch was involved in three cases and the unilateral pedicle in one case.

Despite the severity of the associated lesions and the SCI, 78% (38 patients) did not require intensive care unit (ICU) treatment. The mean length of stay in the ICU was 10.5±6.9 days, with a range of 2–21 days; 50% of the ICU cases lasted 2–4 days.

We found that 39 patients were treated conservatively, whereas 15 were treated surgically. Among the spinal procedures performed, nine were instrumented (Table 7), five instrumented with decompression (Table 8), and one with decompression only, which was a case of unilateral pedicle fracture. Of the surgical group, seven cases had the projectile removed because it was lodged in the spinal canal, and six (85%) presented with a dural lesion. The decision for instrumentation was made according to spinal instability, considering the bone pattern, in which the burst fracture of the vertebral body was the main reason for instrumentation. Patients with bone fragments or a lodged bullet required decompression as well as instrumentation, primarily due to the instability after decompression. Only one patient had a lodged bullet with no instability criteria, and no instability was found after decompression. DiscussionPatient distribution by age and sex is similar to that reported in the literature, with a high incidence in the young adult population, although there were cases of patients aged 9 and 75 years.

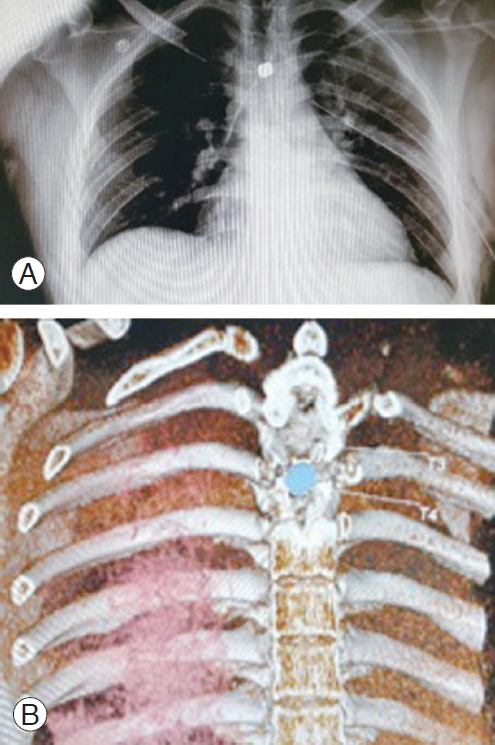

Kaim Khani et al. [2] studied patients with gunshot wounds in general and did not report a spinal injury pattern; some were high-energy injuries, and they did not focus on a particular segment. Unlike the study by Bumpass et al. [6], we describe a simpler pattern. We considered the posterior arch as a unit, given that spinal stability could be more seriously compromised by it than by its individual parts. We used the Magerl/AO fracture classification instead of the Denis three-column model when determining the stability of the vertebral body. We also considered subdividing the cervical segment into the upper and subaxial due to their differences in anatomy and function and in relation to important structures such as the skull, vertebral artery, and mandibular bone. Compared with the study by Jakoi et al. [5], we had a higher incidence of lumbar gunshot wounds than of cervical gunshot wounds, even if both the upper and subaxial were considered together. Chittiboina et al. [7] observed that the trajectory of the missile affected the pattern of the spinal gunshot wound in a predictable manner, in which patients who were shot from behind had a posterior arch fracture. Patients who were shot from the front had a vertebral fracture, and those who were shot from the side had pedicle fractures. We also observed this result when relating the fracture pattern to the associated lesions. As with their series, we noted that in the cases in which the pedicles were involved, there was a very high chance of having a severe or complete SCI. We also found that the thoracic spine was more frequently involved in SCI, possibly due to the transfer of energy to the spinal cord, whereas in the lumbar spine the vertebrae are larger and could absorb this energy better, also the spinal cord. As in the study by Waters and Sie [3], we noted that spinal stability was not compromised if one of the pedicles or facet joints remained intact. Therefore, spinal instability was mainly secondary to vertebral body burst-type fractures (eight cases out of 15). Considering the high risk of evolving into a kyphotic deformity, this type of fracture was the main reason for instrumentation. The second indication for surgery was lodging of the projectile within the spinal canal (Fig. 5). In these cases, we recommend the extraction of the projectile due to the high incidence of dural lesions, as found in our series, that can increase the risk of metal (lead) exposure to the central nervous system. In addition, in patients with debris or bone fragments lodged in the spinal canal, treatment required decompression with or without instrumentation, depending on spinal stability.Concerning the associated lesions, we found that lower GI tract perforation had a great impact, if not the greatest impact of all associated lesions, on the prognosis and treatment. In our experience, this type of injury delays and can even contraindicate surgery due to the high probability of surgical site infection. One of the patients with a lower GI tract lesion was treated and considered for instrumentation, but once in surgery an abscess was found; thus, the patient was treated with debridement and was administered a specific antibiotic treatment based on the culture report.

ConclusionsWe found that the impact of the bullet to the spine created 8 different spinal injury patterns in our series. Based on their frequency, we found two main patterns (the vertebral body and posterior arch) with the pedicles as a modifier because they represent a higher risk for complete or severe SCI. These patterns are usually stable in nature, unless it is a burst fracture of the vertebral body. Vertebral body fractures have a higher frequency of associated lesions independent of the spinal segment due to their anatomical location. The highest incidence of SCI was found in the thoracic spine, with a similar distribution between anterior and posterior spinal patterns. The main indications for surgery were instability, mostly secondary to vertebral body burst fracture, and bullet removal when it was lodged in the spinal canal. Associated injuries influenced the clinical treatment decision, given that they had to be treated with greater urgency than the spinal injury itself. In addition, in some cases, associated injuries can aggravate the patient’s overall health and delay surgery or even contraindicate surgical treatment when necessary. Therefore, the treatment decision remains complex and challenging.

Conflicts of interestNo potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Fig. 1.Posterior arch fracture: sagittal projection with posterior arch fracture.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Vertebral body pattern: Burst-type vertebral body fracture.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Frequency of associated lesions in the thoracic segment

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Frequency of associated lesions in the lumbar segment.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

(A) Bullet lodged in spinal canal: simple X-ray with bullet lodged in upper thoracic level with a pleural tube. (B) Bullet lodged in spinal canal: computed tomography reconstruction of bullet lodged between T3 and T4.

Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of spinal cord injury severity

Spinal cord injury severity Frequency Frankel A 33 Frankel B 3 Frankel C 1 Frankel D 2 Frankel E 14 Total 53 Table 2.Distribution of spinal cord lesion severity by injured segment

Spinal segment Total frequency Spinal cord injury severity Frankel A Frankel B Frankel C Frankel D Frankel E Upper cervical spine 1 0 0 0 0 1 Subaxial cervical spine 7 3 0 0 1 3 Thoracic spine 32 28 0 0 0 4 Lumbar spine 13 2 3 1 1 6 Total 53 33 3 1 2 14 Table 3. Pattern Frequency (%) Posterior arch 17 (34.69) Vertebral body 12 (24.49) Vertebral body+unilateral pedicle 6 (12.24) Disc 4 (8.16) Both pedicles+posterior arch 3 (6.12) Unilateral pedicle 3 (6.12) Unilateral pedicle+posterior arch 2 (4.08) Lateral mass 1 (2.04) Vertebral body+posterior arch 1 (2.04) Table 4.Spinal cord injury related to type of spinal injury

Spinal bone pattern Spinal cord injury Total No Yes % Both pedicles+posterior arch 3 0 3 100 Unilateral pedicle+posterior arch 2 0 2 100 Vertebral body+unilateral pedicle 7 1 6 86 Vertebral body 15 3 12 80 Posterior arch 18 6 12 67 Unilateral pedicle 3 1 2 67 Disc 4 3 1 25 Lateral mass 2 2 0 0 Total 54 16 38 70 Table 5.Severity of spinal cord injury distribution related to spinal injury pattern

Spinal injury pattern Severity of spinal cord injury Total Frankel A Frankel B Frankel C Frankel D Frankel E Both pedicles+posterior arch 1 2 0 0 0 3 Disc 1 0 0 0 3 4 Lateral mass 0 0 0 0 2 2 Posterior arch 10 0 1 2 5 18 Unilateral pedicle 2 0 0 0 1 3 Unilateral pedicle+posterior arch 2 0 0 0 0 2 Vertebral body 11 1 0 0 3 15 Vertebral body+unilateral pedicle 6 0 0 0 1 7 Total 33 3 1 2 15 54 Table 6.Associated lesion frequency according to spinal injury pattern

Associated lesion Spinal injury pattern Posterior arch Vertebral body Vertebral body+unilateral pedicle Disc Both pedicles and posterior arch Unilateral pedicle Unilateral pedicle Lateral mass Lung 2 4 1 2 Hepatic 2 1 Vascular 1 4 1 Spleen 1 1 Lower GI tract 1 3 1 1 1 Diaphragmatic 1 1 1 Pericardial 1 Renal 2 1 Rib fracture 1 Sternum fracture 1 Upper GI tract 1 Total 5 19 3 3 2 3 1 1 Table 7.Instrumented cases according to bony pattern

Spinal injury pattern Frequency Vertebral body 5 Posterior arch 2 Unilateral pedicle+vertebral body 1 Unilateral pedicle+posterior arch 1 Total 9 Table 8.Instrumented and decompression cases according to bony pattern

Spinal injury pattern Frequency Vertebral body 3 Posterior arch 1 Both pedicles+posterior arch 1 Total 5 References 1. Hernandez-Tellez IE, Montelongo-Mercado E, Arreola-Bastidas JJ, Garcia-Valadez LR, Sanchez-Arellano JL, Hernandez-Gomez N. Epidemiology of injuries to the spine by gun fire. Rev Sanid Milit Mex 2015 69:265–74. 2. Ka

Comments (0)