Transverse dimension discrepancies are clinically distinguished as cross-bites when the lower posteriors are positioned either buccally or lingually to the upper posteriors.[1,2] Unilateral or bilateral posterior cross-bites typically associated with transverse maxillary deficiencies are observed in 8–22% of growing patients.[3-5]

Maxillary expansion in the form of slow maxillary expansion (SME) or rapid maxillary expansion (RME) is recommended to improve occlusal relationships[6] and prevent the development of anatomical alterations that may cause functional disturbances.[7] It increases the transverse width with a combination of orthodontic and orthopedic effects through the opening of the midpalatal suture.[8,9] Interceptive correction combined with adequate rehabilitation may restore normal growth and jaw function.[10,11] In general, greater the age of the patient, higher the dental effects and smaller the skeletal changes.[12] It has been reported that RME, associated with tooth/tissue-borne appliances (Hyrax/Haas), has immediate effects and acts by applying heavy forces over a short period of time.[6] A coil spring or quad helix appliance is more commonly associated with SME because it uses continuous low-force systems over a longer period of time, which has been claimed to be a more physiological approach with greater sutural stability.[13,14] Previous studies have claimed that RME minimizes lateral tooth movements and maximizes skeletal displacements while SME promotes bone growth in intermaxillary sutures, leading to greater treatment stability.[15,16] The advantages and disadvantages of each protocol have been assessed with multiple study designs, and yet, the issue remains unclear and controversial because the different devices and methodologies may interfere with comparisons between the two expansion procedures.

Several studies have assessed skeletal, dentoalveolar, and periodontal changes from both expansion modalities through two-dimensional (2D) imaging (lateral/frontal cephalometry, panoramic radiographs, photographs, and plaster models).[17] However, limitations of 2D imaging such as projection errors, distortions, and difficulty in landmark identification due to structure superimposition can influence the generated findings.[18,19] To overcome these limitations, 3D imaging in the form of computed tomography (CT) was first utilized by Timms et al. in 1982 for assessing transverse maxillary dimensions.[20] This was followed by the advent of cone-beam CT (CBCT) which has ushered in a new age of dental diagnostics.[21] CBCT can be used to measure linear dimensions between skeletal and dental landmarks in a real-world setting with the availability of reconstruction software accounting for high precision and accuracy.[22,23] Despite the extensive research and literature available, practitioners’ clinical experience and attitude still have a major role in their choice of RME or SME expansion techniques. As a result, strong evidence is necessitated to defend this preference. Randomized control trials (RCTs) that have evaluated data using 3D techniques were included in the review to increase the reliability of evidence and eliminate bias in the comparison of methods between these two expansion procedures.

This review aimed to evaluate the skeletal and dentoalveolar effects produced by two different maxillary expansion protocols using similar jackscrew expanders through 3D radiographs.

MATERIAL AND METHODS Protocol registrationThe present review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. The review protocol was submitted under the PROSPERO database (CRD42020219075).

Search strategyElectronic databases including PUBMED, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, Scopus, and LILACS along with a complimentary manual search of key orthodontic journals till April 2022 were performed. Keywords were customized for each database and are mentioned in [Table 1].

Table 1: Search keywords and databases.

S. No Database Search terms No. of hits 1 PUBMED (orthodontics) OR (orthodontic patients) OR (fixed orthodontic appliances) AND (slow maxillary expansion) OR (SME) OR (slow mechanical expansion) OR (slow palatal expansion) AND (rapid maxillary expansion) OR (RME) OR (rapid palatal expansion) OR (rapid mechanical expansion) AND (three dimensional evaluation) AND (3 D evaluation) AND (skeletal transverse width) OR (skeletal transverse changes) AND (dental transverse changes) OR (dentoalveolar changes) OR (dental transverse width) 19 2 Google Scholar Three Dimensional AND Rapid AND Slow “Maxillary expansion” AND skeletal and dental changes 77 3 Cochrane Slow maxillary expansion OR SME AND rapid maxillary expansion OR SME AND orthodonticBibliographies of the included full-text articles were scanned for relevant studies. No restrictions were done on the language or date of publication. Duplicate studies from different databases were eliminated manually. Initially, the titles of all studies identified through search strategies were screened by two independent authors, and irrelevant studies were excluded. The screened studies were then subjected to the eligibility criteria. Full texts were then procured for the articles which fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Additional studies were hand-searched from reference lists of all eligible studies to detect any missed publications from databases.

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) analysisPopulation: Growing patients in either mixed or permanent dentition, maxillary transverse discrepancy, unilateral or bilateral cross-bite.

Intervention: Treatment with a fixed expansion device such as a jack screw expander (e.g., Hyrax and Haas) used to achieve RME. Typically activated once a day.

Comparison: Treatment with similar fixed jack screw expander as the intervention group (e.g., Hyrax and Haas) used to achieve SME. Typically activated once/twice a week.

Outcome Primary outcomes3D radiographic assessment of transverse dentoalveolar (intermolar width [IMW], molar inclination) changes.

Secondary outcomes3D radiographic assessment of transverse skeletal changes. Adverse effects such as root resorption, periodontal problems, and patient-reported outcomes such as pain/discomfort.

Eligibility criteria Inclusion criteriaRCT, growing subjects, subjects treated with fixed jack screw expander (e.g., Hyrax and Haas) were included in the study.

Exclusion criteriaControlled clinical trials, retrospective studies, case reports, abstracts, adolescents >13 years, patients undergoing pre-surgical orthodontics, expansion with facemask therapy, cleft lip and palate, and craniofacial syndromes were excluded from the study.

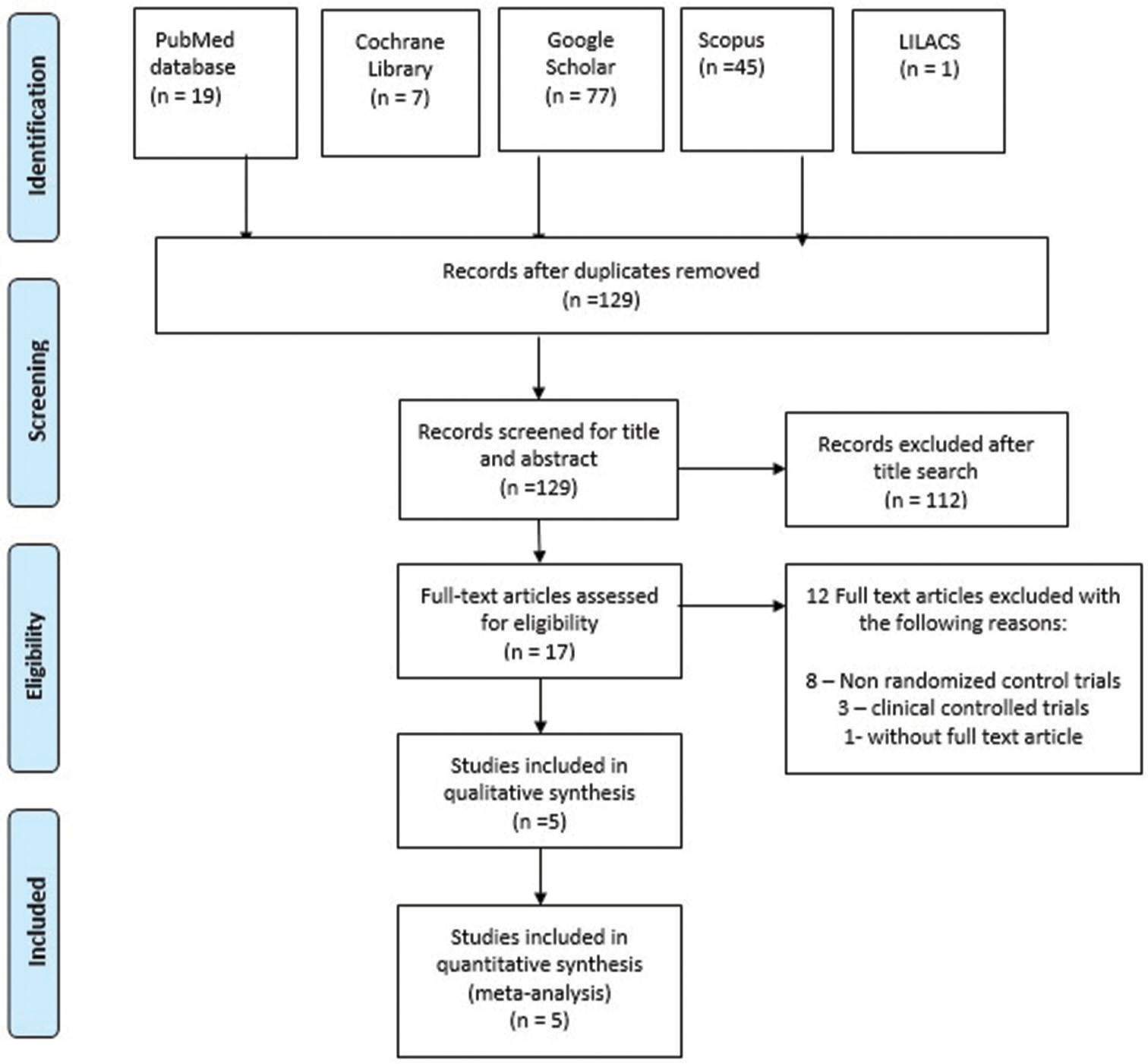

Data collection processStudy selection was done according to the guidelines mentioned in the PRISMA flow chart [Figure 1]. Data required for analysis were extracted by both reviewers (AS and AMG) independently. Disagreements with respect to the data collected were resolved by a third author (PA). Baseline study characteristics of included articles were tabulated and are presented in [Table 2].

Export to PPT

Table 2: Characteristics table of included studies.

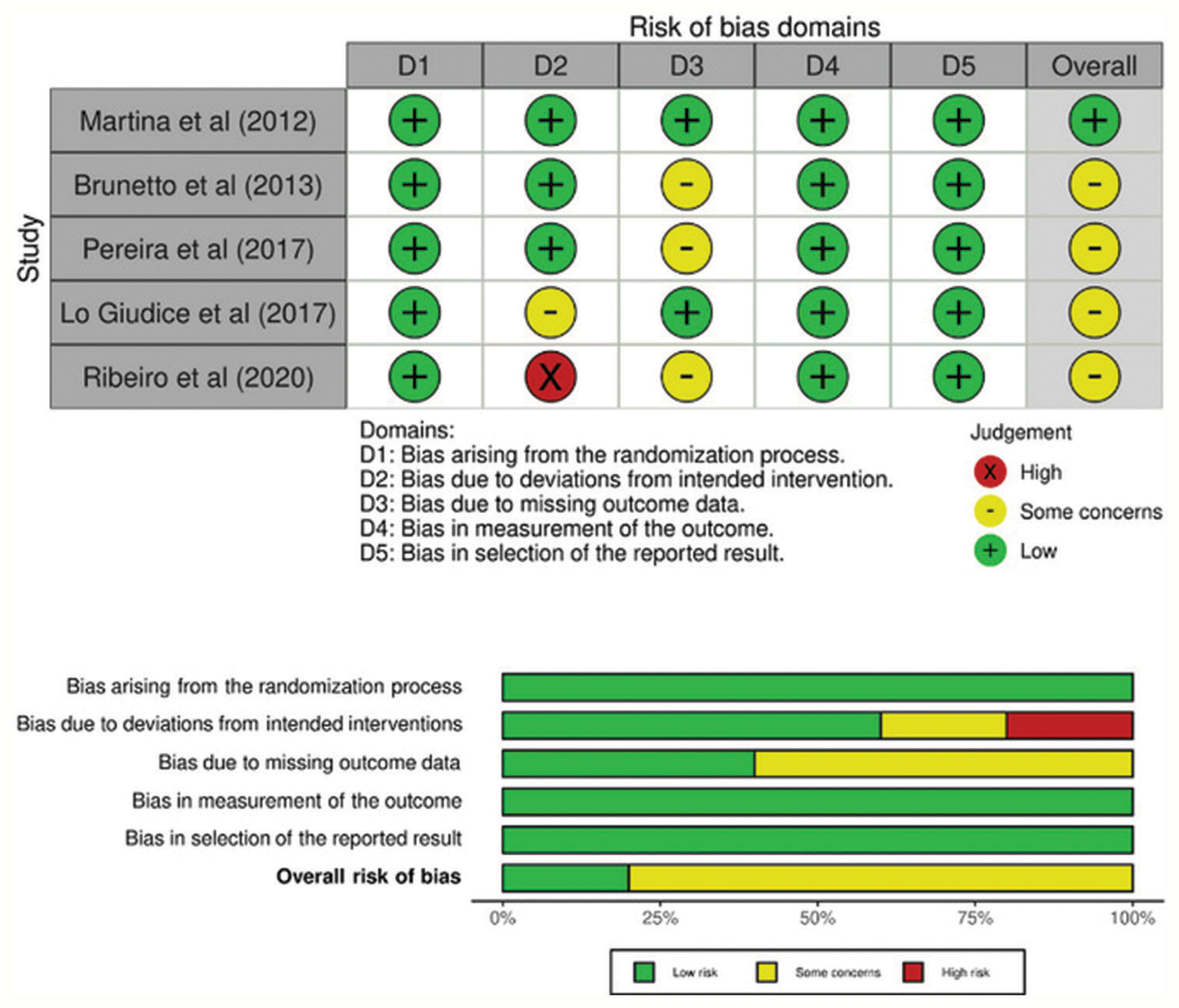

S.Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool utilizing five domains was used for assessing RoB [24] [Figure 2]. Each RCT was then assigned under high, unclear, or low risk. Out of the five domains, even if one domain was unclear or high, then overall RoB becomes unclear or high, respectively. Two authors (AS and AMG) performed the RoB independently and a consensus-based discussion involving a third author (PA) was done to resolve disparities. The Cohen κ test was used to assess agreement level between reviewers and a coefficient value of 0.923 suggested a high degree of agreement.

Export to PPT

Meta-analysisStatistical heterogeneity was evaluated from obtained forest plots of IMW changes, intermolar angle (IMA), and posterior skeletal transverse width changes. A Chi-square test was used to determine heterogeneity where P < 0.1 meant significant heterogeneity. I2 tests were done to quantify the extent of heterogeneity with values of 25, 50, and 75%, corresponding to low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. A random effects model was chosen to determine the pooled estimates. The Tau2 test was used to assess heterogeneity in the random-effects model. Meta-analyses were undertaken using the Review Manager program (RevMan Version 5.3; Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane Collaboration, 2014).

Evidence level of selected articlesAll five[9,25-28] included studies had a Level 2 Evidence design.

RESULTSAn electronic search identified a total of 149 studies. After the removal of duplicates, there were a total of 129 articles, which were subjected to further screening of titles and abstracts. One hundred and twelve articles were excluded and a total of 17 articles were assessed for eligibility. After excluding 12 articles not meeting the eligibility criteria, five studies were identified and included for qualitative and quantitative analysis. The results of the search were illustrated in the PRISMA flow chart [Figure 1]. All the included studies were RCTs. A total of 145 participants were involved, all of whom were treated with either slow or rapid expansion protocols.

RoB of the included studiesResults of RoB for included RCTs are presented in [Figure 2]. Out of five RCTs, one[9] had low RoB whereas the other four[25-28] had some concerns.

3D analysis of transverse dentoalveolar changes between RME and SME IMW at cuspal levelFour RCTs[9,26-28] have assessed IMW at cuspal level following expansion with two different protocols of which only Luiz Ulema Ribeiro et al.[26] reported a significantly greater change in RME when compared to SME (P < 0.001) [Table 3].

Table 3: Results of transverse dentoalveolar changes between RME and SME.

S.Brunetto et al. and Martina et al.[9,27] assessed IMW at apical level and reported significantly lesser expansion in RME compared to SME (P < 0.05) [Table 3].

IMW at alveolar levelPereira et al. and Luiz Ulema Ribeiro et al.[25,26] have assessed IMW at alveolar levels of which Luiz Ulema Ribeiro et al.[26] reported IMW to be significantly greater in RME compared to SME (P < 0.05) [Table 3].

IMAThree studies[9,25,27] have assessed IMA and reported molar inclination to be significantly greater in RME when compared to SME (P < 0.05) [Table 3].

3D analysis of transverse skeletal changes between RME and SME Posterior maxillary expansionThree RCTs[9,25,26] have assessed posterior maxillary expansion of which Pereira et al. and Luiz Ulema Ribeiro et al.[25,26] have assessed posterior apical base width (PABW) and reported a significantly greater increase in RME (P < 0.05). Martina et al.[9] assessed two posterior skeletal parameters (level of pterygoid process and level of greater palatine foramen) and reported expansion at pterygoid process to be significantly greater in RME (P < 0.05) [Table 4].

Table 4: Results of transverse skeletal changes between RME and SME.

S. No Authors Skeletal parameters Landmarks RME (mean±SD) SME (mean±SD) RME-SME Differences and statistically significant differences 1 Martina et al. (2012)[9] Anterior maxillary expansion (mm) Measured at piriform aperture level 2.5±1.5Martina et al. and Brunetto et al.[9,27] have assessed anterior maxillary expansion with varying reference landmarks. Martina et al.[9] assessed at the piriform aperture level with no significant differences between groups. Luiz Ulema Ribeiro et al.[26] assessed anterior apical base width and reported significantly greater changes in RME (P < 0.05) [Table 4].

Skeletal nasal widthLuiz Ulema Ribeiro et al. and Lo Giudice et al.[26,28] assessed skeletal nasal width. Luiz Ulema Ribeiro et al.[26] analyzed anterior and posterior nasal width (PNW) and reported a significant increase in RME (P < 0.05). Contrastingly, Lo Giudice et al.[28] reported PNW to be increased in RME, though not statistically significant (P > 0.05) [Table 4].

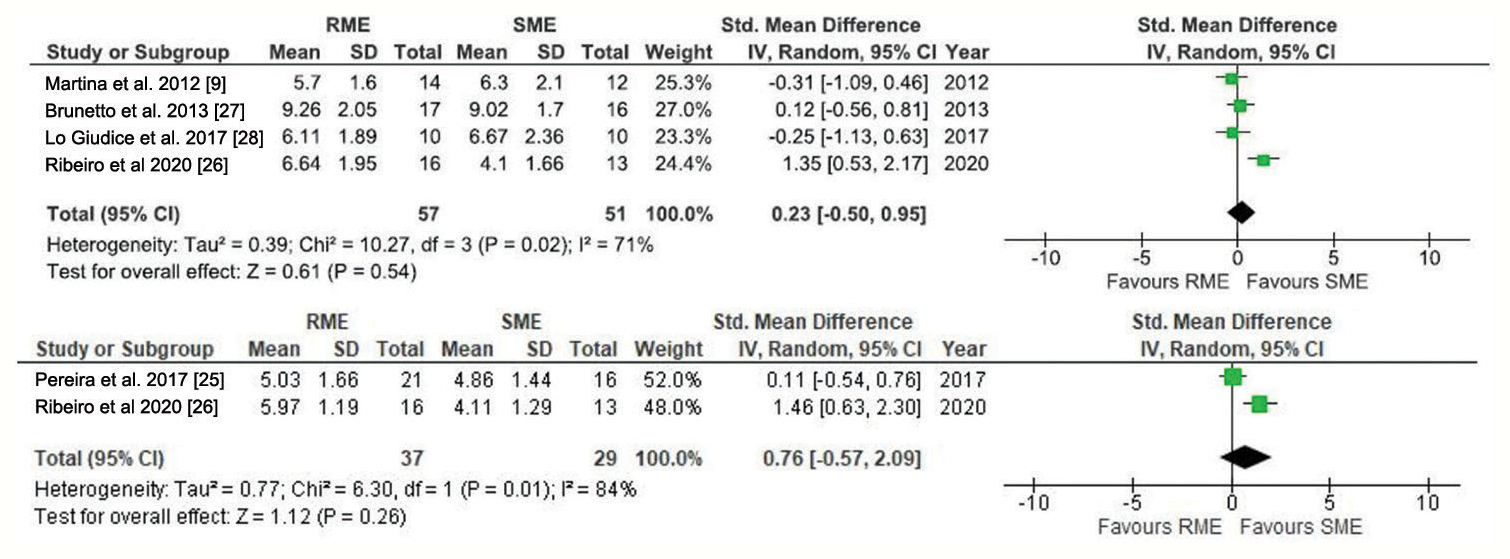

Meta-analysis[Figure 3] is a graphical representation of random-effects meta-analyses done to compare IMW at cuspal level for four studies[9,26-28] and alveolar level for two studies.[25,26] With respect to the cuspal level, overall effect P = 0.54 (SMD = 0.23 [95% Confidence Intervals [CI] = −0.50– 0.95]) indicates no statistically significant changes between groups. Heterogeneity (I2 = 71%) is high and indicates low reliability. With respect to the alveolar level, overall effect P = 0.26 (SMD = 0.76 [95% CI = −0.57–2.09]) indicates no statistically significant changes between groups. Heterogeneity (I2 = 84%) is high and indicates low reliability.

Export to PPT

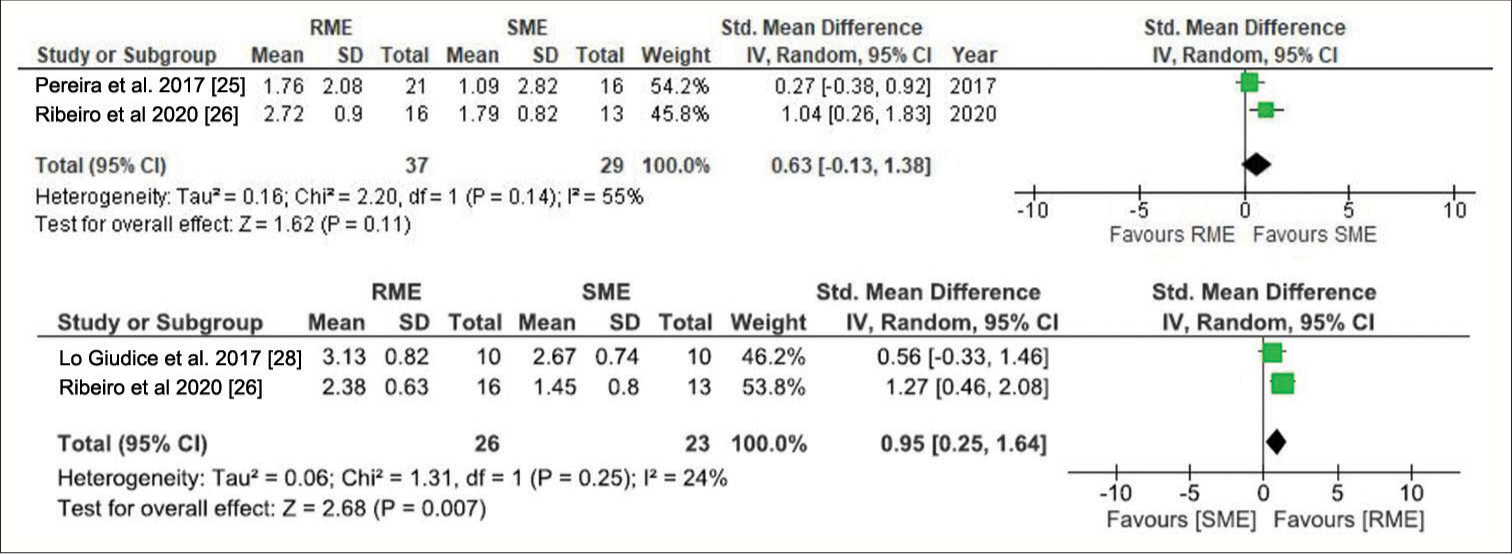

[Figure 4] is a graphical representation of random-effects meta-analyses done to compare PABW and PNW for two studies.[26,28] With respect to PABW, overall effect P = 0.11 (SMD = 0.63 [95% CI = −0.13–1.38]) indicates no statistically significant differences between groups. Heterogeneity (I2 = 55%) is moderate and indicates fair reliability. With respect to PNW, the overall effect P = 0.007 (SMD = 0.95 [95% CI = 0.25–1.64]) indicates a significant increase with RME. Heterogeneity (I2 = 24%) is low and indicates good reliability.

Export to PPT

DISCUSSIONBoth RME and SME are equally effective in correcting developing cross-bites in growing patients.[29] Although multiple studies have compared their effectiveness, they have only been evaluated and quantified using dental casts or two-dimensional (2D) radiographs.[30-32] 3D scans, which utilize precise radiographic slices of CBCTs hold great promise in the diagnosis of transverse discrepancies. In addition, it can be used to generate 3D models when combined with appropriate reconstruction software’s and allows for slice-by-slice assessment to detect the extent of the boundaries with expansion.[19,33] The aim of the review was to evaluate treatment effects produced by RME and SME using 3D dental and skeletal landmarks that can provide clinically relevant information regarding the choice of appliance in treating cross-bites.

Primary outcomes – dentoalveolar changesBoth RME and SME showed similar amount of expansion at cuspal (4.1–9.2 mm) and alveolar level (4.1–5.9 mm) and this degree of dental expansion was identical to findings reported by previous studies.[30,34] RME showed significantly greater molar tipping and decreased IMW at apical level compared to SME. These findings seem to suggest the greater bodily translation of molars in slow expansion after accounting for various factors accumulated from clinical experience. First, a rapid increase in force levels directed at the crown of the molars during RME may have generated a fulcrum effect leading to increased tipping. Second, both SME and RME have different assessment time intervals, with the former being longer. A slower rate of expansion coupled with force dissipation across the entire skeletal unit may have permitted the molars to move through the alveolar housing in a bodily manner. These findings reinforce the need for pre-operative assessment of alveolar bone width before any expansion procedure. Suture position and margins of dentoalveolar structures can be analyzed by 3D imaging before expansion. With regard to the reliability of the findings from the review, meta-analysis between parameters could not be performed owing to the varying landmarks utilized for reference.

Uncontrolled tipping movements may increase root proximity to the buccal alveolar bone, promoting root resorption and adverse periodontal effects.[35] Only one paper[27] reported periodontal bone loss in SME and the author speculated that this may be related to the greater bodily displacement of molars and reduced alveolar bending of anchor teeth. Recent studies have however explained the phenomenon of alveolar bone bending to a greater degree and concluded bodily movement to be more effective in increasing effective arch width.[36,37] Moreover, periodontal findings should be assessed with caution when CBCT scans with lower spatial resolution are used due to the reduced image clarity at the assessment site. Using bonded expanders/occlusal splints, which have superior stiffness, may be effective in reducing adverse periodontal outcomes when deciduous molars are involved.

Secondary outcomes-skeletal changesMartina et al.[9,28] reported that although similar skeletal expansion (about 2.2 mm) occurred at anterior and posterior levels, a minor amount of triangle-shaped expansion was noted at the level of the pterygoid process with RME (detected using 3D radiographs). This may be attributed to a more posterior line of action of the two band expanders employed in RME. However, the inclusion of different activation protocols may have influenced results, as three studies were done until the screw opened 8 mm in both groups, and two studies were done until 2 mm of molar transverse overcorrection was achieved in both groups. Hence, direct comparison of data from included studies is impossible. To make a comparison of different expansion protocols, a simple mathematical model has been proposed to assess the nasal or palatal width as a percentage of IMW.[26] Out of five RCTs, two[28] have assessed skeletal nasal width (as a proportion of IMW) and reported RME to have a significant skeletal nasal width increase. The results of the meta-analysis have shown low heterogeneity and good reliability. Since external walls of the nasal cavity are close to maxillary sutures, they may expand laterally as a result of this expansion. Consequently, RME may be beneficial in improving intranasal capacity, treat nasal deformity, mouth breathing, and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Lo Giudice et al.[28] reported an approximate increase of 46% with RME and 33% with SME, whereas Luiz Ulema Ribeiro et al.[26] reported 36% with RME and 35% with SME. Percentage differences between the studies may be due to different expansion protocols and expander designs. Only one study[9] reported RME patients to have higher levels of pain and discomfort, especially during initial activation. This may be due to the difference in the nature of forces–heavy and intermittent in RME, light and continuous in SME. However, these results should be viewed with caution as they have moderate evidence.

Comments (0)