T2D is a polygenic disease in which insulin resistance brought on by overnutrition, obesity, age, and a high genetic risk profile leads to the loss of glycemic control (1, 2). While many individuals exhibit insulin resistance, the loss of β-cell function in response to mounting metabolic stress determines whether euglycemia is maintained. Thus, to understand the pathogenesis of T2D, we must also know how the β-cell responds to metabolic stress and why it fails, especially in the pre-diabetic stage of the disease.

Compelling evidence exists that endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (3), mitochondrial dysfunction (4), cytokine signaling (5) and the loss of cell identity (6) all contribute to the loss of β-cell function in response to metabolic stress. Moreover, over 600 genetic risk loci for T2D have been identified by genome-wide association studies (GWAS) (7–9). While the target genes for most risk loci have not been unambiguously determined, islet-specific transcription factors often bind nearby, suggesting in many cases that they predispose β-cells to fail (10–12).

To develop a mechanism-based explanation for β-cell failure that integrates both genetic and biochemical knowledge, we build on several recent reviews (13–17) and summarize recent studies that point to the dysregulation of intracellular Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]i) as a unifying explanation for the seemingly diverse mechanisms and genes that may contribute to β-cell failure in response to metabolic stress.

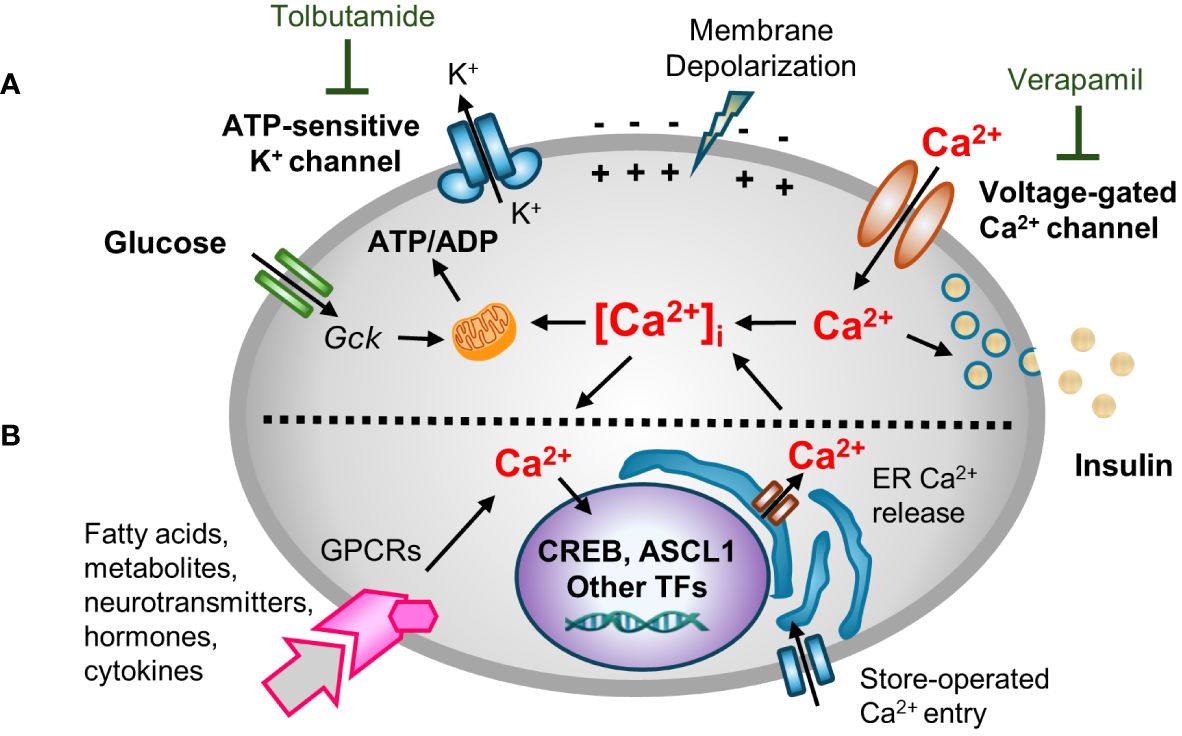

2 Metabolic stimuli-insulin secretion couplingCa2+ is a critical second messenger that regulates many cellular processes in β-cells, insulin exocytosis being foremost among them (18). Decades of studies have provided a now canonical model for metabolism-stimulated insulin secretion (19). Briefly, and as illustrated in Figure 1A, a rise in the plasma glucose concentration is sensed by the β-cell through the metabolism of glucose leading to an increase in the cellular ATP/ADP ratio. The rise in ATP/ADP ratio causes ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel closure, plasma membrane depolarization, the opening of voltage‐gated Ca2+ channels (VDCC), and a rise in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]i). The transient spikes in [Ca2+]i stimulate docking and exocytosis of insulin vesicles (20).

Figure 1 A multifaceted role for [Ca2+]i in β-cell function. Hyperglycemia and other insulin secretagogues cause [Ca2+]i in β-cells to increase. (A) Metabolism-stimulated insulin secretion. Glucose and amino acid metabolism lead to an increase in the ATP/ADP ratio, causing KATP (ATP-sensitive) potassium channel closure, plasma membrane depolarization, and the opening of voltage‐gated Ca2+ channels (VDCC) triggering transient increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]i). The transient spikes in [Ca2+]i stimulate docking and exocytosis of insulin vesicles. The activity of KATP and VDCC channels can be blocked with tolbutamide (a sulfonylurea) and verapamil, respectively. (B) Adaptive regulation. Hormones, cytokines, neurotransmitters, and certain fatty acids and metabolites that signal through G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) activate intracellular signal transduction pathways that cause Ca2+ efflux/influx from intracellular stores/extracellular space. GPCR-induced alterations in [Ca2+]i modify other metabolism-based insulin secretory responses. In addition, Ca2+ signaling to the nucleus alters the expression Ca2+-dependent transcription factors that control many cellular functions.

Blocking KATP channel activity, either by the administration of sulfonylureas or by genetic disruptions, causes depolarization of the plasma membrane. Conversely, use of diazoxide, a molecule that opens the KATP channel, or expression of KATP channel subunits (encoded by Kcnj11 and Abcc8) that contain activating mutations, causes hyperpolarization of the plasma membrane (21–24). However, while the canonical model nicely links cell metabolism to insulin secretion and predicts an increase in [Ca2+]i in response to metabolic stress, it overlooks the now well-established fact that [Ca2+]i affects other β-cell organelles, such as the ER, mitochondria, and nucleus (15, 25, 26). Moreover, while the rise of [Ca2+]i is principally metabolism-driven, insulin exocytosis is modulated by many other agents including many hormones, fatty and amino acids, and neurotransmitters in so-called “amplifying pathways”. Many of these agents act by binding to G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), and the activation of phospholipase C (PLC)/protein kinase C (PKC) or adenylate cyclase (AC)/protein kinase A (PKA) pathways which rely on Ca2+ for signaling (27–30). An extended model (Figure 1B) recognizes both the role of other agents in modulating insulin secretion, and the critically important role of Ca2+ in other organelles.

2.1 Ca2+ is essential for many functions of the β-cell[Ca2+]i is tightly regulated by transmembrane channels and pumps, Ca2+ buffering proteins, and by the uptake and release of Ca2+ from ER stores and mitochondria (31). Ca2+ concentrations vary considerably among different subcellular compartments, with concentrations in extracellular space (~1–2 mM) and ER and Golgi compartments (~200–700 µM) being more than ten thousand times higher than in the cytosol (~100 nM) (32, 33). Mitochondria Ca2+ concentrations vary between 50–500 nM in order to regulate metabolism and serve as a transient calcium buffer (34). Metabolic stimulation causes [Ca2+]i to sharply increase from basal levels of ~100 nM to stimulated levels of ~1–3 µM due to Ca2+ entry from the extracellular space or Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. These spikes in [Ca2+]i may start locally before propagating as cyclical Ca2+ oscillations throughout the islet (35, 36). While Ca2+ spikes are tightly linked to insulin secretion, an increase in [Ca2+]i also directly affects Ca2+ concentrations in various organelles, including the nucleus, through multiple influx/efflux pathways (37).

2.2 Role of Ca2+ in the ER and mitochondriaBoth the ER and mitochondria require Ca2+ for their function, and both serve as intracellular Ca2+ reservoirs. The ER is critical for protein synthesis and folding, lipid synthesis, and Ca2+ storage and release, and β-cells require optimal ER functionality to support the production of insulin and to maintain [Ca2+]i homeostasis (25). The entry and release of Ca2+ from and to the ER is mainly regulated by SERCA pumps, or by inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3R) and by ryanodine receptors (RyR), respectively. Moreover, store-operated Ca2+ entry from the extracellular space plays a critical role in maintaining ER Ca2+ concentrations. Dysfunctions in any of these processes can change ER susceptibility to stress (38, 39). Not only does ER Ca2+ affect the unfolded protein stress response (40), persistent ER stress likely causes β-cell demise in both Type 1 and T2D (25, 41). Indeed, cytokine-induced depletion of Ca2+ from the ER may directly trigger apoptosis (42).

Mitochondrial activity and metabolic enzymes are also regulated by Ca2+ (43, 44). Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion is directly linked to mitochondrial function, and Ca2+ flows between the ER and mitochondria via mitochondria-associated ER membrane (MAMs) contact sites. Since Ca2+ is released from the ER and directly taken up by mitochondria, intraluminal ER, mitochondrial matrix, and cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations are closely interrelated (45, 46). ER-mitochondria interplay may also be a critical cellular adaptive mechanism for restoring [Ca2+]i homeostasis after episodes of Ca2+ overload, thereby also contributing to β-cell dysfunction (47, 48).

2.3 Ca2+ signaling to the nucleusCa2+ signaling to the nucleus links signaling cues with gene expression, enabling cellular adaptations to both internal and external stimuli (49). This process, known as excitation-transcription coupling, is well-described in neurons and myocytes (50–53). Ca2+ influx in response to membrane depolarization and GPCR activation triggers multiple intracellular signaling pathways that regulate cell identity, proliferation, autophagy and cell death (54). Glucose stimulation leads to increase in β-cell nuclear Ca2+ concentration (55, 56). [Ca2+]i is sensed by Ca2+-binding proteins (CBPs), with calmodulin being the most well-studied (57). These molecules in turn activate downstream targets, including the protein phosphatase calcineurin and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinases (e.g. CamKII and CamKIV), which in turn modulate the activity of Ca2+ responsive transcription factors such as NFAT and CREB (58–62), as well as a number of other transcription factors, transcriptional co-regulators and chromatin modifying enzymes (63, 64). While excitation-transcription coupling is a part of a normal response to changes in the cell environment, chronic and sustained activation of Ca2+ signaling pathways is detrimental to cell function (65–67).

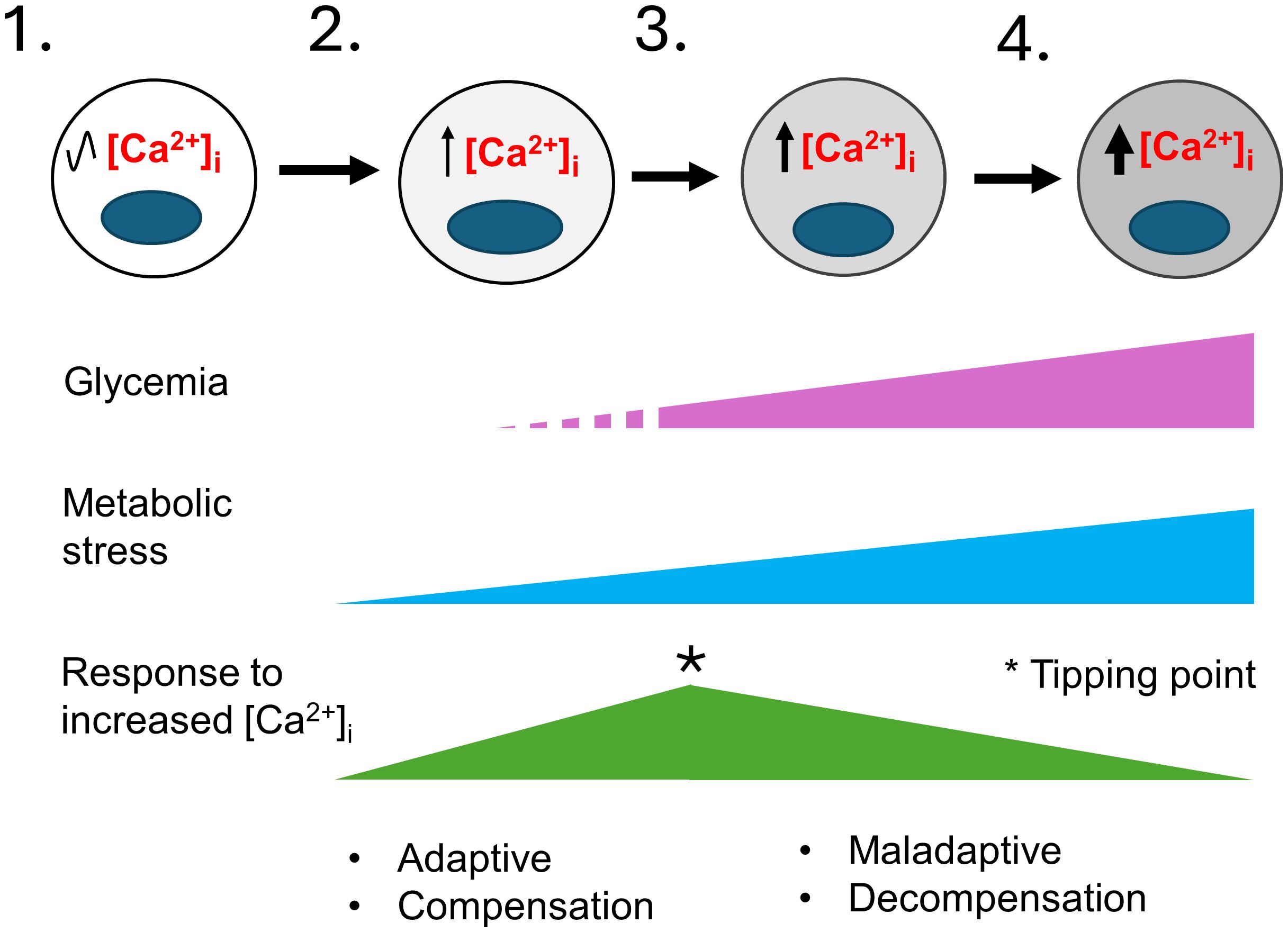

2.4 Evidence linking Ca2+ signaling to β-cell failureWhile the harmful effects of excess [Ca2+]i have been extensively investigated in other excitable cell types, and a critical role for Ca2+ signaling in β-cell function has long been clear, we lack a clear understanding of how Ca2+ signaling is linked to β-cell failure (13–17). Prior studies have shown that basal [Ca2+]i is increased in rat islets cultured in high glucose (68), in mouse islets from obese (db/db) mice (69–71), in islets from mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) (72), and in β-cells that exhibit chronic membrane depolarization due to the loss of KATP channel subunit Abcc8 (73). Conversely, lowering [Ca2+]i in β-cells by blocking Ca2+ influx with verapamil (74–78), other compounds (79), or by a genetic deletion of Cavβ3, a voltage-dependent calcium channel subunit (80), attenuates β-cell loss and diabetes in mice and humans. Moreover, studies in which β cells are “rested” through the use of diazoxide, which opens the KATP channel thereby impairing membrane depolarization, or other therapies that lower the blood glucose concentration or reduce glucokinase activity, may all work in large part by limiting increases in [Ca2+]i (41, 71). However, while there is ample evidence showing a correlation between a sustained increase in [Ca2+]i and impairments in β-cell function, we do not know how metabolic stress-induced increases in [Ca2+]i, which are likely to only be transient during the pre-diabetic phase of T2D, initiate events that lead to β-cell failure, as illustrated in Figure 2. Similarly, we do not know how specific Ca2+-regulated processes are affected by T2D-associated risk loci, either individually or in combination.

Figure 2 A model for the development of T2D that considers the role of metabolic-stress and [Ca2+]i. This model illustrates the stepwise failure of β-cells in response to metabolic stress. 1) In healthy individuals β-cells have normal [Ca2+]i levels. 2) In pre-diabetes, environmental factors such as age, sex, genetic makeup, obesity, and overnutrition cause insulin resistance and an increase in insulin demand resulting in mild metabolic stress. Transient elevations of the blood glucose and other insulin secretagogues cause the hyperstimulation of β-cells and small increases in [Ca2+]i. Initially, the increase in Ca2+-signaling stimulate insulin secretion, β-cell proliferation and other adaptive responses that continue to maintain glycemia and compensate for increased insulin demand. 3) The limited ability of β-cells to compensate together with a continuing rise in metabolic stress cause further increases in [Ca2+]i. A tipping point occurs where a network of Ca2+-regulated genes crucial for maintaining Ca2+ homeostasis and β-cell function becomes maladaptive. 4) The maladaptive changes brought on by chronically elevated [Ca2+]i cause the loss of β-cell identity and function, with β-cells entering a decompensation stage where they can no longer secrete enough insulin to maintain normal blood glucose. Glucolipotoxicity further accelerates the loss of β-cell function, identity and viability, therefore resulting in overt T2D. The increased gray shading of β-cells from left to right indicates increasing loss of β-cell identity and function. The * indicates a tipping point.

3 Effects of metabolic stress related increases in [Ca2+]i on pancreatic β-cell gene expression3.1 Models of excess Ca2+ signaling in β-cellsConsistent with the canonical model (Figure 1), depolarization of the plasma membrane is predicted to cause Ca2+ influx, a rise in [Ca2+]i, and an increase in insulin secretion. Abcc8 and Kcnj11 knockout mice, both of which lack functional KATP channels and exhibit a sustained elevation in [Ca2+]i, display mild hypoglycemia as young animals but develop diabetes as they age (73, 81–85). Similarly, in humans, several individuals with inactivating mutations of the KATP channel that cause hyperinsulinism in infancy have been reported to develop diabetes in adolescence (86, 87). The findings that both mice and humans with genetically-driven increases in [Ca2+]i maintain euglycemia for several months before they cross over to being overtly diabetic has important implications (73, 82). First, it clearly separates the effects of a sustained pathological increase in [Ca2+]i, often referred to as excitotoxity, from glucotoxicity, which occurs after the onset of hyperglycemia. Second, the delay has enabled studies of how β-cell gene expression and function is affected by a chronic increase in [Ca2+]i without the confounding effects of hyperglycemia (73, 82, 88).

3.2 Overlapping effects of excitotoxicity and overnutritionStudies of Abcc8 knockout mice revealed alterations in islet morphology and glucose intolerance prior to the development of hyperglycemia. In addition, they revealed a loss of β-cell identity that correlated with a marked alteration of a network of Ca2+ regulated genes (73). Recently, studies of β-cell-specific Kcnj11 knockout mice, which also exhibit an increase in [Ca2+]i and glucose intolerance, revealed a Gs/Gq signaling switch (89).

Since overnutrition is common in pre-diabetes, we compared transcriptomes of FACS-purified β-cells of Abcc8 knockout mice, which serve as a model for excitotoxicity, with mice fed a HFD (88). Both excitotoxicity and overnutrition were found to affect overlapping sets of genes, and to exert an additively negative effect on β-cell function (88). The commonalities in transcriptional response are not surprising since overnutrition, by elevating circulating free fatty acids (FFAs), contributes to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia (90) by causing the release of Ca2+ from ER stores, increase in [Ca2+]i and accentuating both ER and oxidative stress (16, 91–95).

While excitotoxicity and overnutrition individually perturb the expression in β-cells of several thousand genes (88), a meta-analysis revealed that many of the upregulated genes were involved in oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondrial organization, metabolic pathways, and oxidative stress response whereas downregulated genes were involved in cell organization, secretory function, cell adhesion, cell junctions, cilia, cytoskeleton, and regulation of β-cell epigenetic and transcriptional program (88). Furthermore, many genes that are dysregulated excitotoxicity and overnutrition are altered in pre-diabetic and diabetic β-cells from db/db mice (96), also suggesting a strong correlation between chronic alterations in [Ca2+]i and the loss of β-cell function.

3.3 Transcriptomic changes that precede β-cell failure3.3.1 Mitochondrial function and energy metabolismA chronic increase in [Ca2+]i stimulates expression of mitochondrial structural and metabolic genes (Me3, Cox7a) that is parallelled by increased oxygen consumption and mitogenesis in islets (88). Chronic stimulation of the electron transport chain leads to an increase in reactive oxygen species and to mitochondrial dysfunction (97). Furthermore, the combination of increased [Ca2+]i and overnutrition not only impairs mitochondrial function, but it may also impair the replacement of metabolically damaged mitochondria (88) due to the downregulation of mitophagy associated genes (Clec16a, Prkn) (88, 98–100).

Lysosomes are of note since they are involved in maintaining the mitochondrial biogenesis/mitophagy balance (101), and stressed β-cells showed an increase in regulators for mitochondrial (Ppargc1a) and lysosomal (Tfeb) biogenesis (88), both known to be activated by Ca2+ in other cell types (102, 103). Ppargc1a, a key transcriptional regulator of energy metabolism, FA β-oxidation and mitochondrial biogenesis is implicated in β-cell dysfunction and T2D (104–106).

Metabolic stress, by increasing the expression of genes that contribute to metabolic inflexibility, may also impair the ability of β-cells to utilize glucose, which would impair their metabolic response to glucose (107). Consistent with this, an increase in the expression of FA β-oxidation genes, as well as Pdk4, a kinase that inhibits pyruvate flux into the TCA cycle (108), and decrease in mitochondrial respiration response to glucose also suggests that stressed β-cells switch to FAs and ketones as mitochondrial fuels (88).

Together, these findings suggest that metabolic-stress induced elevations in [Ca2+]i cause impairments in mitochondrial function that reduce the ability of β-cells to respond to glucose, an unambiguous sign of β-cell failure.

3.3.2 ER protein folding and protein glycosylationExcitotoxicity and overnutrition also cause an increase in the expression of genes associated with ER secretory stress (88, 109). Glycosylation, the process during which glycans (mono- or oligosaccharides) are attached to proteins in the ER and Golgi, is a critical quality control signal in ER protein folding (110). Since excess protein glycosylation brought on by ER stress is linked to cellular apoptosis (111), the observed increases in expression of genes associated with ER protein folding and N- and O-linked protein glycosylation are highly noteworthy as they suggest that the stability, localization, trafficking, and function of glycosylated receptors, ion channels, nutrient transporters, and transcription factors in β-cells may all be adversely affected (112).

3.3.3 β-cell structure: cytoskeleton, cell polarity, and cell adhesionSince islet architecture in Abcc8 knock-out mice is abnormal (73), it is not surprising that many genes important for β-cell structure and function downregulated (88), including those necessary for cell adhesion and cell-cell junctions (113), cilia (114), and cytoskeletal and vesicular trafficking (115). Our transcriptomic analysis also predicts changes in β-cell polarity since genes essential for apical domain formation, primary cilia, and the lateral domain are all downregulated while genes associated with the vasculature-facing basal domain are upregulated (116). Together, the many changes we observed suggest that a chronic increase in [Ca2+]i disrupts cell polarity, exocytotic machinery, and critical cell-cell contacts, thereby physically disrupting islet architecture and insulin secretion.

3.3.4 Chromatin maintenance and β-cell identityCellular dedifferentiation and the resulting loss of β-cell identity are fundamentally important contributors to β-cell dysfunction in T2D (117, 118). In β-cells that are stressed by excitotoxicity and overnutrition, many transcription factors that are essential for maintaining β-cell identity are downregulated (88). Similarly, epigenetic modifiers, including a DNA methyltransferase (Dnmt1) important for silencing of developmental or “disallowed” metabolic genes in mature β-cells (119), are decreased. This likely explains the upregulation of multiple disallowed genes (120) in response to metabolic stress (88). Several lncRNAs which contribute to the maintenance of the epigenetic and transcriptional landscape of β-cells (121), are also down-regulated. Importantly, Aldh1a3 (122) and Bach2 (123), two well-established markers and drivers of β-cell dedifferentiation, are upregulated, suggesting that they too are regulated by Ca2+ (88). Thus, the continued expression of key transcription factors necessary to maintain β-cell identity likely also depends on the maintenance of Ca2+-signaling and homeostatic regulation.

3.4 Role of Ascl1, a Ca2+-regulated gene, in β-cell dedifferentiation and failureWhile the expression of many genes in β-cells is altered by metabolic stress, the chronic nature of the analyses performed to date limits the establishment of direct cause-and-effect relationships. For this reason, we sought to identify a Ca2+-regulated gene that could be studied in detail. Ascl1 (Achaete-scute homolog 1) stood out since many of the genes putatively upregulated by [Ca2+]i contain binding sites for ASCL1 (73). In addition, Ascl1 is a pioneer transcription factor critical for neural cell differentiation (124–126) and is necessary for the formation of neuroendocrine cells in multiple tissues (127–129). Importantly, ASCL1 is also expressed in human islets (130).

To investigate how Ascl1 contributes to β-cell dysfunction during metabolic stress, we generated β-cell-specific Ascl1 knockout mice and studied their responses to both excitotoxicity and overnutrition. We found that Ascl1 is indeed induced by stimuli that cause Ca2+-signaling to the nucleus, and that it contributes in multiple ways to the loss of β-cell function. Remarkably, the removal of Ascl1 from β-cells improved their function in response to metabolic stress by HFD feeding (131). Transcriptional profiling of islets under different experimental conditions revealed that ASCL1 contributes to a loss of β-cell function both by activating a dedifferentiation program and by suppressing the expression of secretory and innervation genes in response to overnutrition.

Interestingly, β-specific Ascl1 knockout islets from HFD mice have increased expression of parasympathetic neuronal markers, increased insulin secretion in response to acetylcholine, and an increased islet innervation. While additional studies of the role of Ascl1 in stressed β-cells are necessary, our experiments clearly demonstrate that a metabolic stress-induced increase in Ca2+-signaling to the nucleus alters both β-cell function and identity in an ASCL1-dependent manner. Our studies also point to a role for other Ca2+-regulated transcription factors, suggesting that a Ca2+-dependent gene regulatory network is critical for the proper function of β-cells, and that metabolic-stress profoundly modifies this network by invoking both adaptive and maladaptive transcriptional changes.

4 DiscussionAlthough multiple lines of evidence point to Ca2+-signaling being intimately involved in metabolic stress-induced β-cell failure, the mechanisms whereby an increase in [Ca2+]i leads to a loss of β-cell function are not understood and need further investigation.

1. Temporal causality between changes in [Ca2+]i, the expression of key transcription factors, and the loss of β-cell function needs to be established.

2. We need to better understand how specific Ca2+-regulated processes modulate β-cell function. Cleverly designed studies are required to distinguish between the effects of elevated metabolic flux and closely linked [Ca2+]i.

3. We need to determine how overnutrition and insulin resistance affect Ca2+ spiking activity in pre-diabetic setting.

4. We need to better understand how Ca2+-mediated transcriptional reprogramming impairs β-cell function and identity.

5. Finally, we need to determine how specific T2D genetic risk loci affect Ca2+-dependent processes in β-cells.

While our assertions for the importance of Ca2+-signaling have strong experimental support, we do not understand how genetic risk loci, either individually or in aggregate, may contribute to β-cell dysfunction.

We hope that this mini-review stimulates investigations by others as there is much to learn about how alterations in [Ca2+]i affect β-cell function and contribute to T2D.

Author contributionsMM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AO: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The studies described herein were supported by institutional and philanthropic funds from Vanderbilt University.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank Pamela Uttz for skillfully proofing of the text.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References2. Muoio DM, Newgard CB. Mechanisms of disease: molecular and metabolic mechanisms of insulin resistance and beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2008) 9:193–205. doi: 10.1038/nrm2327

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Torres JM, Abdalla M, Payne A, Fernandez-Tajes J, Thurner M, Nylander V, et al. A multi-omic integrative scheme characterizes tissues of action at loci associated with type 2 diabetes. Am J Hum Genet. (2020) 107:1011–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.10.009

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Mahajan A, Taliun D, Thurner M, Robertson NR, Torres JM, Rayner NW, et al. Fine-mapping type 2 diabetes loci to single-variant resolution using high-density imputation and islet-specific epigenome maps. Nat Genet. (2018) 50:1505–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.09.001

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Suzuki K, Hatzikotoulas K, Southam L, Taylor HJ, Yin X, Lorenz KM, et al. Genetic drivers of heterogeneity in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology. Nature. (2024) 627:347–57. doi: 10.3390/ijms20246110

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Pasquali L, Gaulton KJ, Rodriguez-Segui SA, Mularoni L, Miguel-Escalada I, Akerman I, et al. Pancreatic islet enhancer clusters enriched in type 2 diabetes risk-associated variants. Nat Genet. (2014) 46:136–43. doi: 10.1038/ng.2870

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Rosengren AH, Braun M, Mahdi T, Andersson SA, Travers ME, Shigeto M, et al. Reduced insulin exocytosis in human pancreatic beta-cells with gene variants linked to type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. (2012) 61:1726–33. doi: 10.2337/db11-1516

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Miguel-Escalada I, Bonas-Guarch S, Cebola I, Ponsa-Cobas J, Mendieta-Esteban J, Atla G, et al. Human pancreatic islet three-dimensional chromatin architecture provides insights into the genetics of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. (2019) 51:1137–48. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0457-0

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Gilon P, Chae HY, Rutter GA, Ravier MA. Calcium signaling in pancreatic beta-cells in health and in Type 2 diabetes. Cell Calcium. (2014) 56:340–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.09.001

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Newsholme P, Gaudel C, McClenaghan NH. Nutrient regulation of insulin secretion and beta-cell functional integrity. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2010) 654:91–114. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-3271-3_6

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Nichols CG, York NW, Remedi MS. ATP-sensitive potassium channels in hyperinsulinism and type 2 diabetes: inconvenient paradox or new paradigm? Diabetes. (2022) 71:367–75. doi: 10.2337/db21-0755

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Aguilar-Bryan L, Clement J, Gonzalez G, Kunjilwar K, Babenko A, Bryan J. Toward understanding the assembly and structure of KATP channels. Physiol Rev. (1998) 78:227–45. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.227

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

24. Brereton MF, Ashcroft FM. Mouse models of beta-cell K(ATP) channel dysfunction. Drug Discovery Today Dis Models. (2013) 10:e101–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmod.2013.02.001

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

29. Kebede MA, Alquier T, Latour MG, Poitout V. Lipid receptors and islet function: therapeutic implications? Diabetes Obes Metab. (2009) 11 Suppl 4:10–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01114.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Varney MJ, Benovic JL. The role of G protein-coupled receptors and receptor kinases in pancreatic beta-cell function and diabetes. Pharmacol Rev. (2024) 76:267–99. doi: 10.1124/pharmrev.123.001015

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Zampese E, Pizzo P. Intracellular organelles in the saga of Ca2+ homeostasis: different molecules for different purposes? Cell Mol Life Sci. (2012) 69:1077–104. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0845-9

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

34. Romero-Garcia S, Prado-Garcia H. Mitochondrial calcium: Transport and modulation of cellular processes in homeostasis and cancer (Review). Int J Oncol. (2019) 54:1155–67. doi: 10.3892/ijo

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

35. Fridlyand LE, Tamarina N, Philipson LH. Bursting and calcium oscillations in pancreatic beta-cells: specific pacemakers for specific mechanisms. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. (2010) 299:E517–32. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00177.2010

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

36. Fletcher PA, Thompson B, Liu C, Bertram R, Satin LS, Sherman AS. Ca(2+) release or Ca(2+) entry, that is the question: what governs Ca(2+) oscillations in pancreatic beta cells? Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. (2023) 324:E477–E87. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00030.2023

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

37. Laude AJ, Simpson AW. Compartmentalized signalling: Ca2+ compartments, microdomains and the many facets of Ca2+ signalling. FEBS J. (2009) 276:1800–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06927.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

38. Luciani DS, Gwiazda KS, Yang TL, Kalynyak TB, Bychkivska Y, Frey MH, et al. Roles of IP3R and RyR Ca2+ channels in endoplasmic reticulum stress and beta-cell death. Diabetes. (2009) 58:422–32. doi: 10.2337/db07-1762

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

39. Sabourin J, Le Gal L, Saurwein L, Haefliger JA, Raddatz E, Allagnat F. Store-operated ca2+ Entry mediated by orai1 and TRPC1 participates to insulin secretion in rat beta-cells. J Biol Chem. (2015) 290:30530–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.682583

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

41. Kalwat MA, Scheuner D, Rodrigues-Dos-Santos K, Eizirik DL, Cobb MH. The pancreatic ss-cell response to secretory demands and adaption to stress. Endocrinology. (2021) 162(11):bqab173. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqab173

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

42. Ramadan JW, Steiner SR, O’Neill CM, Nunemaker CS. The central role of calcium in the effects of cytokines on beta-cell function: implications for type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Cell Calcium. (2011) 50:481–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.08.005

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

43. Wiederkehr A, Wollheim CB. Impact of mitochondrial calcium on the coupling of metabolism to insulin secretion in the pancreatic beta-cell. Cell Calcium. (2008) 44:64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.11.004

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

45. Huang DX, Yu X, Yu WJ, Zhang XM, Liu C, Liu HP, et al. Calcium signaling regulated by cellular membrane systems and calcium homeostasis perturbed in alzheimer’s disease. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2022) 10:834962. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.834962

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

46. Barazzuol L, Giamogante F, Cali T. Mitochondria Associated Membranes (MAMs): Architecture and physiopathological role. Cell Calcium. (2021) 94:102343. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2020.102343

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

47. Vig S, Lambooij JM, Zaldumbide A, Guigas B. Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria crosstalk and beta-cell destruction in type 1 diabetes. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:669492. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.669492

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

48. Madec AM, Perrier J, Panthu B, Dingreville F. Role of mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane (MAMs) interactions and calcium exchange in the development of type 2 diabetes. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. (2021) 363:169–202. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2021.06.001

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

52. Ma H, Khaled HG, Wang X, Mandelberg NJ, Cohen SM, He X, et al. Excitation-transcription coupling, neuronal gene expression and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2023) 24:672–92. doi: 10.1038/s41583-023-00742-5

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

53. Dewenter M, von der Lieth A, Katus HA, Backs J. Calcium signaling and transcriptional regulation in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. (2017) 121:1000–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310355

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

54. Patergnani S, Danese A, Bouhamida E, Aguiari G, Previati M, Pinton P, et al. Various aspects of calcium signaling in the regulation of apoptosis, autophagy, cell proliferation, and cancer. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21(21):8323. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218323

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

55. Quesada I, Rovira JM, Martin F, Roche E, Nadal A, Soria B. Nuclear KATP channels trigger nuclear Ca(2+) transients that modulate nuclear function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2002) 99:9544–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142039299

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

56. Quesada I, Martin F, Roche E, Soria B. Nutrients induce different Ca(2+) signals in cytosol and nucleus in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. (2004) 53 Suppl 1:S92–5. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2007.S92

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

58. Heit JJ, Apelqvist AA, Gu X, Winslow MM, Neilson JR, Crabtree GR, et al.

Comments (0)