Dear Editor,

Lacosamide, an anticonvulsant drug approved in 2008, is used for partial-onset seizures and status epilepticus in adults. It enhances sodium channel inactivation and modulates collapsin response mediator protein-2 and GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) receptors.1 Common adverse events include dizziness, headache, drowsiness, sinus bradycardia, hyponatremia, and elevated liver and muscle enzymes.2

Cutaneous side effects are common with anti-epileptics but rare with lacosamide, with a few reports of rashes, dermatomyositis, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. However, no nail changes have been reported with lacosamide.2

A 24-year-old man presented with a chief complaint of painful erythematous nails persisting for 20 days. The patient had suffered a severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) in a road traffic accident one month prior, for which he was prescribed lacosamide as a preventive measure against early-onset post-traumatic seizures (PTS). Ten days after starting lacosamide, the patient developed purpura on multiple nails. Subsequently, he experienced heightened pain across all nails, accompanied by the emergence of subungual haematomas within the next five days. By the tenth day, the haematomas exhibited hemopurulent discharge from the proximal end of the nail, leading to onychomadesis in multiple nails post-drainage.

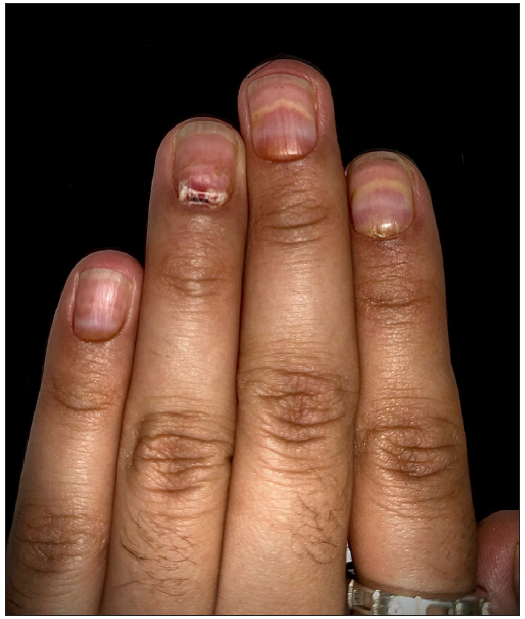

Upon cutaneous examination, the patient had nail dyschromasia, onychomadesis, subungual haemorrhages, subungual haematomas, and multiple pus-filled lakes under the proximal nail plate with orangish discolouration of the proximal nail bed [Figures 1a and 1b]. All nails were symmetrically involved. Onychoscopy revealed onychomadesis, with a homogeneously coloured deep red-to-purple proximal subungual haematoma [Figures 2a and 2b]. The haematoma displayed a filamentous distal end with a convex distal border of onycholysis precisely parallel to the distal nail fold. Additionally, some nails exhibited a convex semicircular distal yellowish-white band at the lesion’s distal edge, indicating the deposition of purulent material at the haematoma’s distal border along with a well-defined orangish semicircular ‘rising sun’ appearance of the proximal nail bed and nail matrix [Figure 2c].

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

No fungal elements were discerned upon KOH mount examination. Laboratory investigations, including routine hemogram, coagulation profile, liver profile, renal profile, and serological assessments for HIV, syphilis, and VDRL, were all within normal limits. The Naranjo adverse drug reaction (ADR) probability score was six, signifying a ‘probable’ ADR.

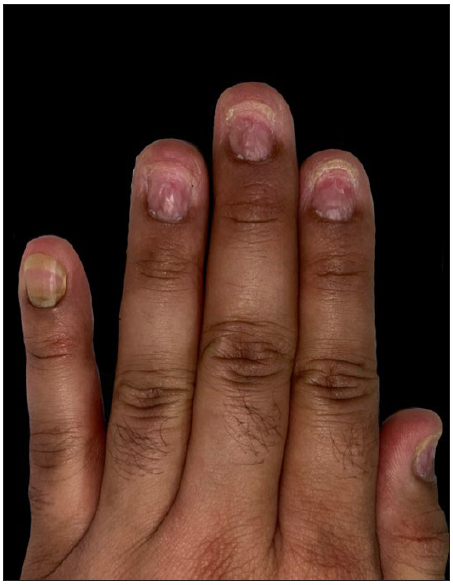

Clinical and onychoscopic assessment led to a diagnosis of lacosamide-induced hemorrhagic onychomadesis, with a recommendation to stop lacosamide. The patient was treated with daily nail soaking in a povidone-iodine antiseptic solution. Additionally, oral cefixime and vancomycin were administered for two weeks, resulting in notable clinical improvement [Figures 3a and 3b]. Vancomycin was chosen due to bacterial cultures showing gram-positive organisms in the discharge and to prevent potential Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection during the patient’s extended hospital stay.

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Post-treatment, the patient was transitioned to the alternative anticonvulsant, levetiracetam, four weeks later. Notably, the lesions did not reoccur following the discontinuation of lacosamide.

Nail changes are rare with anticonvulsant therapy, but onychomadesis is linked to certain drugs like valproic acid, carbamazepine, and phenytoin.3

Additional factors responsible for onychomadesis across all nails encompass high fever and viral infections, none of which were evident in our case. While previous literature has not documented instances of lacosamide-induced nail alterations, we hypothesise that akin to other anticonvulsants, lacosamide might disrupt the typical keratinisation process of nail matrix keratinocytes, consequently leading to onychomadesis. In our case, the conspicuous emergence of haemorrhage beneath the nail surface could result from drug-induced acute decline or cessation of mitotic activity in nail matrix keratinocytes with the formation of subungual haemorrhagic bulla.

Given the uniform impact on all nails in our case, along with corresponding involvement across matching regions, we strongly suspect the involvement of an underlying drug. As per existing literature, scrutiny should extend to any medication administered within 2–3 weeks before the onset of nail symptoms.3,4

Differential diagnoses include pemphigus vulgaris, atypical hand-foot-mouth disease, and bullous lichen planus of the nails.5 To date, a sole report exists concerning hemorrhagic onychomadesis within a case series of ten cases following selenium toxicity.5 The authors suggested that chronic selenium toxicity may lead to hemorrhagic onychomadesis due to impaired clotting factor synthesis in the liver.5 However, our patient’s coagulation profile was within normal limits.

This is the first documented case of drug-induced haemorrhagic onychomadesis, highlighting the need for more research on lacosamide’s effects on nail health.

Comments (0)