Globally, the burden of cancer has increased and put higher stress on the healthcare system. Any advanced cancer patient experiences functional and cognitive impairment continuously after diagnosis, followed by an unpredictable phase of clinical and functional decline. To overcome the complications of cancer, i.e., physical distress, functional dependence, psychological distress and weakness, there is a requirement for family support from months to years to fight against cancer along with the health-care system.[1] The increased incidence of female-aged populations with gynaecological cancer has resulted in significant healthcare costs of 3.8 billion dollars, with an average cost of 6,293 dollars per patient and increased clinical complexity.[2] The World Health Organization (WHO) defined palliative care (PC) to advanced cancer patients as always resulting in increased staff costs, including PC services and specialised PC.[3,4] In developed countries like the United States, specialised PC hospitals had more than and equal to 50 beds, and that increased by 178% between 2000 and 2016, from 25% in 2000 to 75% in 2016.[5,6] One out of every five advanced cancer patients dies in a hospital, and death in institutional care persists into the later stages of life, which always pays a very high amount to any country’s health system and economy, too.[7]

PC includes symptom management and care during the end-of-life phase for almost every cancer, including gynaecological cancer, at hospices, hospitals and at home.[8-10] Studies have shown that PC not only improves treatment quality but also improves clinical outcomes for all cancer patients, including gynaecological cancer.[2,11] Caregivers are the main key support for any cancer patient. PC can be provided by assisting unpaid caregivers or family members as they are family who love and care for their loved ones, and it is also required during the grief and bereavement process.[12] By knowing gynaecological cancer patient’s quality of life and their caregivers, we can generate research evidence and implement their PC in the future. The present study focused on comparing specialist PC with conventional care for patients who have advanced gynaecological cancer and their caregivers.

MATERIALS AND METHODSFour randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were included for comparison of PC versus conventional care on quality of life, burden and depression level of cancer patients and their caregivers, including gynaecological cancer. All studies looking for primary or secondary outcomes of gynaecological cancer were eligible.

Participants were patients who were diagnosed with advanced cancer, received specialist PC and had a compromised quality of life were included. Unpaid caregivers were family members or significant others, and those who received a pre-bereavement intervention from specialist PC staff to manage bereavement-related problems were included.

We decided to include studies in which patients get PC intervention provided in hospitals, hospices and home settings by a PC team. Unpaid caregivers were adults and patients’ family members or significant others who were receiving hospital inpatient, outpatient or outreach PC services and received intervention. We considered trials that compared PC to standard treatment. Trials excluded research in which PC was provided by only PC practitioners (pain management and oxygen therapy) because that did not consider holistic PC.

Outcome measures were primary as well as secondary outcomes were derived from previous relevant RCTs. Results reflect the multifaceted character of PC, i.e., patients received direct and indirect patient care, and caregivers received care, too. Primary outcomes were patients’ health-related quality of life and burden of symptoms, as the primary goal of PC. Quality of life was measured by health-related quality of life scales, and the burden of symptoms was the collection of two or more symptoms that include social, physical, spiritual and psychological domains as reported by patients using any validated scale. The secondary outcomes were patient and caregiver depression was assessed with validated depression assessment scales as secondary outcomes.

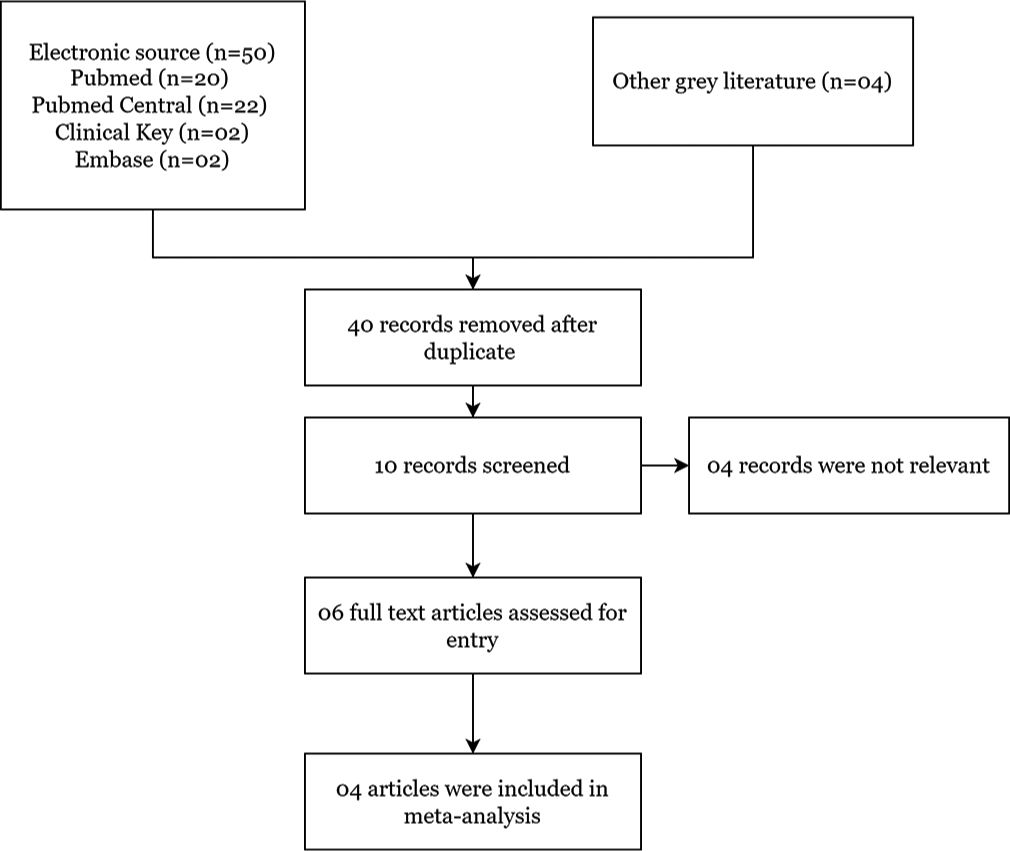

The search strategy used in this study was electronic searches (PubMed [n = 20], PubMed Central [n = 22], Clinical Key [n = 02] and Embase [n = 02]) and other grey literature searches were used to find RCTs. Only the English language is restricted, and research from 2011 to 2021 was included. By utilising electronic searches and using MeSH terms, we found four relevant papers.

Included studies titles and abstracts found in our electronic searches were independently examined by two authors (CVK and KKR). If there was any ambiguity about the study’s eligibility after reading the abstract, we retrieved full-text RCTs for further evaluation, and two authors (PG and VL) reviewed those articles again. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions were followed and used Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses[13] (Higgins 2011a) guidelines to resolve disagreements by discussion [Figure 1].

Export to PPT

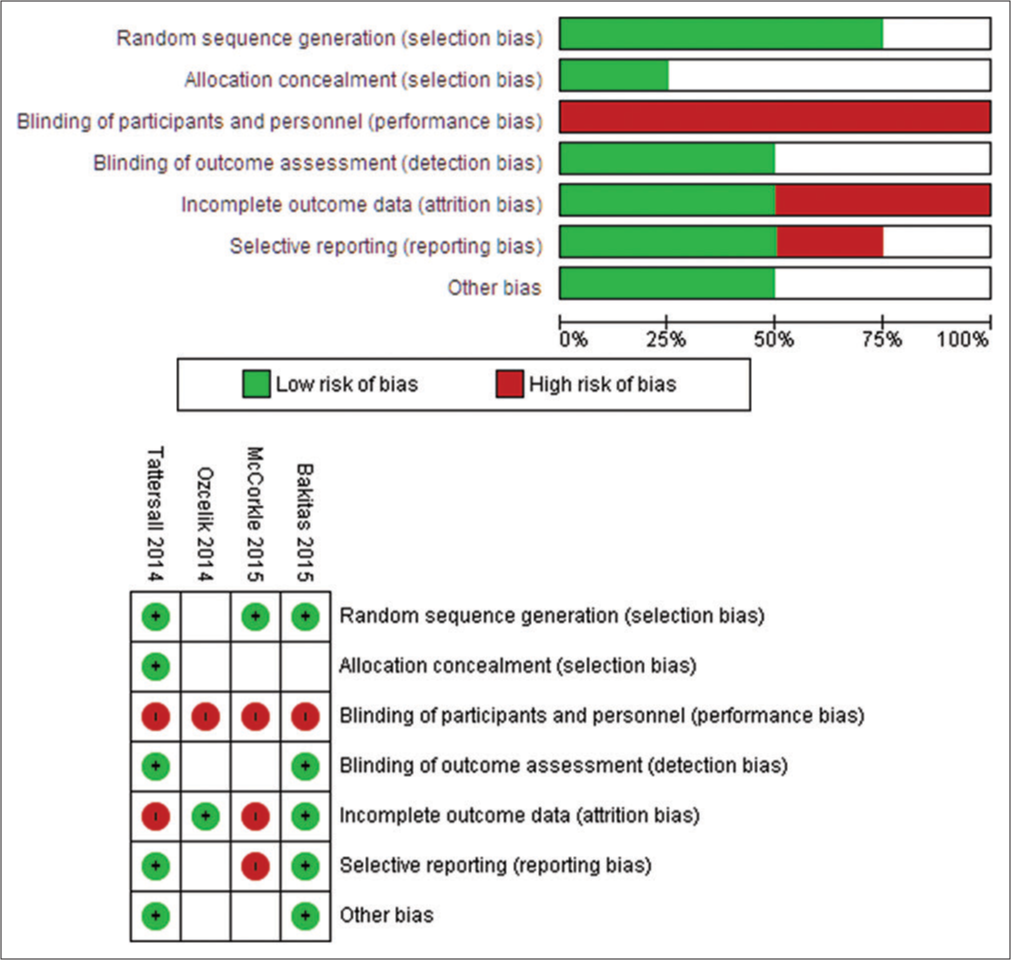

Extraction and management of data done by two authors (CVK and KKR) extracted relevant data from RCTs using a data extraction form. Review Manager (RevMan 4.0) was used to enter data (RevMan 2014). The data extraction form was previously used in a study and again assessed for its efficacy. We gathered enough information about the included studies to create an ‘Included Studies Characteristics’ list [Table 1]. Included studies’ risk of bias done by following Cochrane criteria, two reviewers (CVK and KKR) assessed the risk of bias by following the risk of bias assessment tool and creating a risk of bias graph and risk of bias summary for the included study [Figures 2 and 3].

Table 1: Included study characteristics.

Author Intervention Sample size (intervention/control) Life expectancy Outcome Certainty of evidence (GRADE) Tattersall et al. (2014) [14] Nurse-led intervention 60/60 Life expectancy of <12 months MQoL questionnaire; RSC checklist; SCNS-Short Form Questionnaire Low Ozcelik et al. (2014) [15] Multidisciplinary team 22/22 Life expectancy from 6 and 12 months ESAS Assessment System; EORTCQLQ-C30 Quality of Life Questionnaire; FAMCARE questionnaire Very low McCorkle et al. (2015) [16] Multidisciplinary team 66/80 Late-stage cancer diagnosis within

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Assessment of heterogeneity amongst four included studies was inspected for checking heterogeneity based on the findings of our meta-analysis, i.e., inspection of forest plots and use of I2 statistics for assessing the extent of heterogeneity (Higgins 2011a). Data synthesis was done by including means, standard deviations and frequencies of the included study and tabulated to provide the main elements of included studies that were eligible for meta-analysis (Rodgers 2009). Evidence of high quality of included studies’ outcomes was judged by two authors (CVK and KKR) independently using Grade Profiler Guideline Development Tool (GRADE pro-GDT 2015) software and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention criteria. The GRADE method assessed the quality of the body of evidence for each included study outcome using five criteria (publication bias, consistency of effect, study limitations, imprecision and indirectness) (Higgins 2011a). The grading system assigns grades to high to very low evidence based on their criteria [Table 1].

RESULTSWe included 50 studies searched by records retrieved from various electronic searching databases and four additional records from other grey sources. By removing duplicate studies by two authors (CVK and KKR), four studies were finally included [Figure 1]. The design of all four included RCTs were comprised of one fast-track RCT, one cluster RCT and two studies that had parallel design. Sample sizes ranged from 22 to 104 participants. Total recruitment time in RCTs ranges from 1 month to 12 months. We used data from 670 people in total, including 289 adults with advanced cancer patients, including gynaecological cancer and 381 unpaid caregivers.

Advanced cancer patient participants, including gynaecological cancer and their unpaid caregivers/family members, were subjects of four included studies (Tattersall et al., 2014,[14] Ozcelik et al., 2014;[15] McCorkle et al., 2015,[16] and Bakitas et al., 2015[17]). The average age of cancer patients ranged from 34.2 to 62.2 years. Four studies were included, each with the same number of male and female patients.

We included four studies, in which one study (Bakitas et al., 2015)[17] provides palliative services intervention based on the telephone for rural populations, another outpatient service (Tattersall et al., 2014)[14], an inpatient consultation (Ozcelik et al., 2014)[15] and a service provided across various settings, including hospital (McCokle 2015). One study (Bakitas et al., 2015)[17] included an advanced PC team including PC clinicians and nurse specialists, while the other three studies stated that professionals who delivered specialist-level interventions were involved (Tattersall et al., 2014; Ozcelik et al., 2014; McCorkle et al., 2015).[14-16] In 3 studies, early PC was included (Tattersall et al., 2014; Ozcelik et al., 2014; McCorkle et al., 2015).[14-16] In one study, patients with advanced cancer were diagnosed between 30 and 60 days before (Bakitas et al., 2015).[17] One study (McCorkle et al., 2015)[16] looked at patients who had been diagnosed with advanced-stage cancer within the previous 100 days. In one study, ambulatory patients with newly diagnosed metastatic cancer were included (Tattersall et al., 2014).[14] Theoretically grounded: Case conference/management was included in one study, i.e., Ozcelik et al. 2014.[15] PC participated in two studies (Ozcelik et al., 2014; Bakitas et al., 2015)[15,17] that provided unpaid caregiver/family assistance and provided counselling to assist patients and unpaid caregiver/family members. One study was only focused on the patient (Ozcelik et al., 2014)[15], while the other three were focused on both the patient and the family (Tattersall et al., 2014; McCorkle et al., 2015 and Bakitas et al., 2015).[14,16,17] We included care coordination as a new category since the need for coordinated care with advanced disease is not always met, leading to more hospitalisations and poor clinical outcomes. The results of PC were compared with the control group by following conventional care. RCTs showed a poor description of conventional care, with very little information supplied. The control group in Bakitas et al. 2015 trial was kept under specialist care, including PC physicians, nurse specialists, physiotherapists and other treatment services. Inpatient palliative treatment was also available to all patients as needed. After 4 weeks, observation was done for the control group. In the remaining three studies, standard care was included, and engagement of PC professionals was done if needed (Tattersall et al., 2014; Ozcelik et al., 2014; McCorkle et al., 2015).[14-16]

Out of the four included studies, the key outcomes were health-related quality of life (Tattersall et al., 2014; Ozcelik et al., 2014; McCorkle et al., 2015; Bakitas et al., 2015)[14-17] and symptom burden (Tattersall et al., 2014, Ozcelik et al., 2014, McCorkle et al., 2015, Bakitas et al., 2015).[14-17] All four studies included early PC and reported symptom burden in cancer populations, including gynaecological cancer (Tattersall et al., 2014; Ozcelik et al., 2014; McCorkle et al., 2015; Bakitas et al., 2015).[14-17] Depression was also reported in two studies among patients (McCorkle et al., 2015; Bakitas et al., 2015)[16,17] and their caregivers (Ozcelik et al., 2014; Bakitas et al., 2015)[15,17] [Figure 2].

We excluded four studies because one was not RCT, one RCT followed PC as routine care, one RCT did not follow sequence allocation, and one RCT intervention was not given by the PC team. Risk of bias in included studies was done using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (Higgins 2011b), i.e., selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting and other biases were all identified and reported and found high risk for bias for included studies.

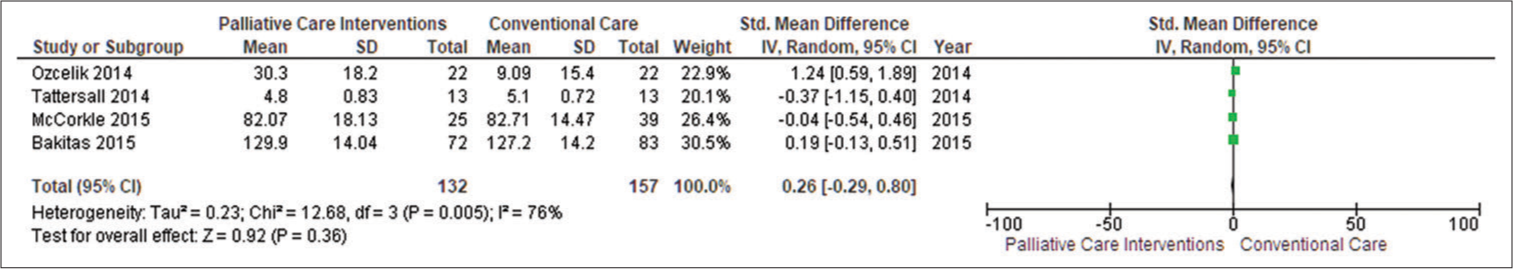

Primary outcome Patient’s health-related quality of lifeFour studies included quality of life with adjusted endpoints (Ozcelik et al., 2014; Tattersall et al., 2014; McCorkle et al., 2015; Bakitas et al., 2015).[14-17] PC was found helpful in enhancing patient’s quality of life (standardised mean differences [SMD] = 0.26; 95% confidence interval [CI] −0.29–0.80; I2 = 76%) when data from four studies reporting endpoint data with 289 patients were pooled where positive SMDs imply that higher level of patient’s quality of life.

According to traditional standards, the effect size obtained (0.92) is high (Cohen 1988). By computing SMDs across RCTs in meta-analyses, we were able to combine diverse scales for assessing patient health-related quality of life. The funnel plot revealed some symmetry in general. Egger’s asymmetry test yielded a P = 0.36. This symmetry is not indicative of any publishing bias, as evidenced by the publication of positive research in the funnel plot [Figure 3].

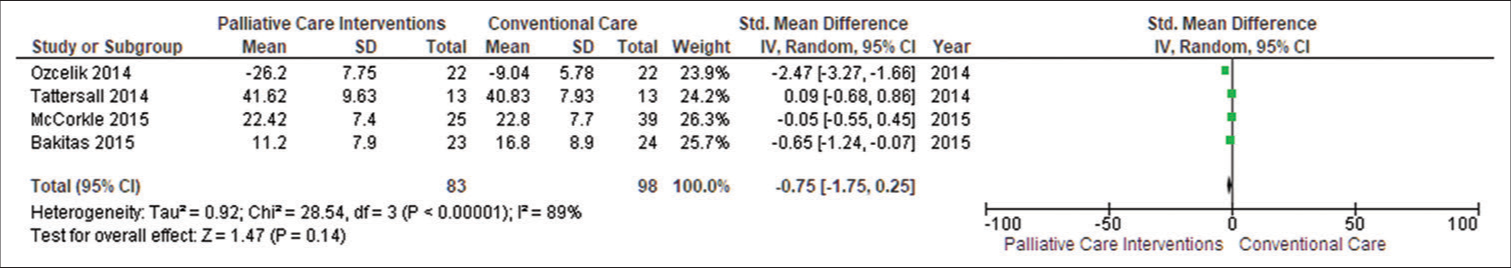

Patient’s symptom burdenWe extracted data from four studies (Tattersall et al., 2014; Ozcelik et al., 2014; McCorkle et al., 2015; Bakitas et al., 2015).[14-17] SMDs demonstrated that PC was beneficial in reducing patients’ symptom burden (SMD −0.75, CI −1.75–0.25; I2 = 89%). Negative SMDs suggest benefits, i.e., lower symptom burden faced by patients in PC intervention. The funnel plot revealed symmetry in general. Egger’s asymmetry test yielded a P = 0.14. This symmetry is indicative of no publishing bias, as evidenced by the publication of positive research in the funnel plot. Due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 89%) in our main meta-analysis, we performed subgroup analysis, too [Figure 4].

Export to PPT

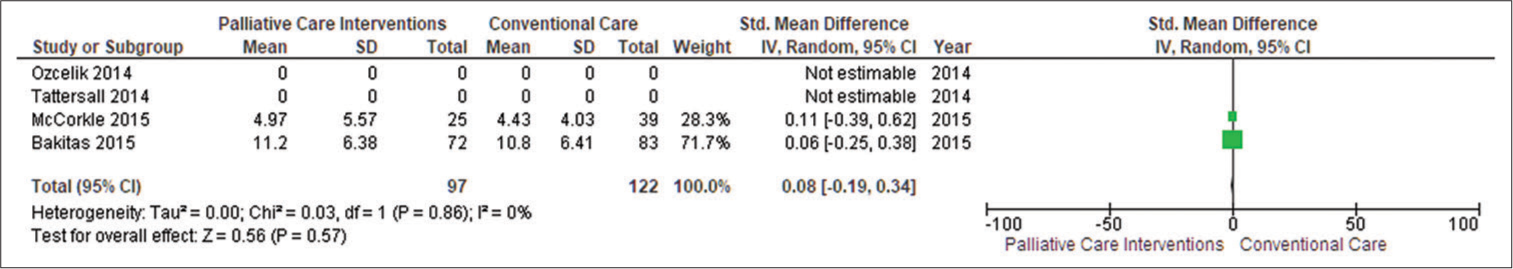

Secondary outcome Patient’s depressionWe included data from two studies (McCorkle et al., 2015; Bakitas et al., 2015)[16,17], and SMDs demonstrated that PC was beneficial in reducing patient depression (SMD 0.08, CI −0.19–0.34; I2 = 0%). Positive SMDs imply increased patient depression, indicating that patients were under mild depression. The funnel plot revealed some symmetry in general. Egger’s asymmetry test yielded a P = 0.57. This symmetry is indicative of no publishing bias, as evidenced by the publication of positive research in the funnel plot with low heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) [Figure 5].

Export to PPT

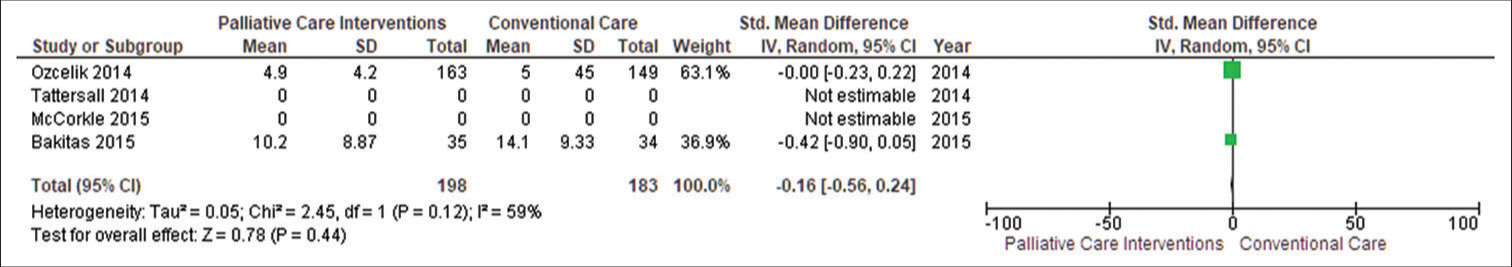

Caregiver’s depressionTwo studies (n = 381) reported caregivers’ depression, and they discovered that PC did not affect caregivers’ depression (SMD −0.16, 95% CI −0.56–0.24; I2 = 59%). Negative SMDs indicate benefit, i.e., unpaid caregivers who were receiving PC intervention had lower depression as compared to the conventional care group. The funnel plot revealed some symmetry in general. Egger’s asymmetry test yielded a P = 0.44. This symmetry is indicative of no publishing bias, as evidenced by the publication of positive research in the funnel plot. Sensitivity analysis yielded an SMD of −0.16 (95% CI −0.56–0.24; I2 = 59%; n = 2 studies; n = 381 individuals) [Figure 6].

Export to PPT

Information given by PC intervention was valuable to patients and caregivers/families since it ensured awareness of illness and treatment alternatives too. The PC team’s diverse nature and specialised knowledge were valued by patients and caregivers/families, and integrating PC with oncology resulted in improved patient care.

DISCUSSIONSignificant healthcare costs have been incurred due to a rise in the incidence of gynaecological cancer in older female populations. The main results summary showed that evidence for advanced cancer patients, including gynaecological cancer, is of low to poor quality. It further demonstrated minimal benefits for patients’ quality of life and burden of symptoms. Comparing PC with conventional care, PC improves patients’ quality of life, as evident from positive SMD values. When PC symptom burden was compared with conventional care, the results showed negative SMD values, which suggested its benefit, i.e., PC is also helpful in lowering symptom burden amongst patients. RCT results suggested that PC reduces patient depression on average. Evidence also suggests that PC decreases depression in unpaid caregivers through PC intervention.

Symptom management, coping and support were a key component of PC addressed in the research.[18] Care coordination and future planning were also addressed in several of the studies. Certified PC experts were included in the included RCTs, but they were unsure about the PC training of those providing PC team members for symptom control, care coordination, coping and support.[19]

The transition from a hospital to a home-based care feature was also very challenging and inconsistent. Health policy, PC and resources in developed countries differ from those in developing countries, where PC is still in its early stages (WHO 2014).[20] The findings from developing countries’ healthcare systems may not be applicable to developing countries’ environments. The included papers were related to all cancer patients, but this study revealed that the PC of gynaecological cancer still needs to be revealed more.[21]

In certain ways, this review agrees with previous reviews, particularly in terms of health-related quality of life. With small effect sizes, we discovered that PC improves patient health-related quality of life by reducing symptom burden and decreasing patient and caregiver depression.[11] We also discovered that PC improved some of the secondary outcomes we looked at, i.e., patient depression level. Evidenced quality ranged from very low to low level. Another meta-analysis (Gaertner et al. 2017)[22] also identified the effect of PC on health-related quality of life (SMD 0.16 with moderate-quality evidence).

Potential risk of biasGiven that subjective decisions may influence decisions made during meta-analysis, it is critical to address any potential biases that have occurred. In general, meta-analysis procedures promote transparency and standardisation, improving the process’s reproducibility. We merged RCTs reporting adjusted endpoint data because these studies employed various scales and combined their SMDs for meta-analysis outcomes such as patient’s quality of life, burden of symptoms and depression amongst patients and unpaid caregivers. Pooled studies were lower, which again limited our major meta-analysis findings.

Implications for practiceAccording to low to very low-quality evidence, advanced cancer patients may benefit from PC in terms of small improvements in quality of life, less burden of symptoms and reduced patient and caregiver depression levels. There was no evidence that PC caused significant harm, and included RCT evidence was poor quality and insufficient to form a firm judgement. Cancer patients can talk to their physicians and ask for a referral to a PC unit. Population-based forecasts show that in the future, PC requirements will rise (May et al., 2019) [23] so policymakers must focus their efforts on expanding PC commissions.

CONCLUSIONPC improves cancer patients’ quality of life and reduces their burden of symptoms. It also reduces depression among patients and their caregivers as compared to conventional care. PC assists cancer patients in dying at the place of their choice (home death), including gynaecological cancer. We believe that until more recent exclusive RCTs are available, the findings should be interpreted with caution. Evidence of PC’s influence on major harms was found to be of very low quality. PC appears to have cost no more than standard care.

Comments (0)