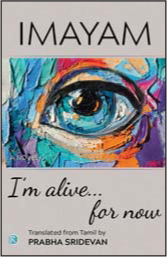

I’m alive . . . for now (a novel). Imayam (translated from Tamil by Prabha Sridevan). Ratna Books, Delhi, 2024. ₹699, 325pp. ISBN 978–93–56873–66–7.

The reverse of the title page specifies that this is a work of fiction, followed by the usual disclaimer that names, characters, places and incidents are used fictitiously and resemblance to actual persons, events and locales are entirely coincidental. However, I am, or was (having retired some years ago) a nephrologist, and I find the description of the symptoms and the mental state of the protagonist to be authentic. Clearly the author has deep knowledge of the condition and the thoughts of a patient with end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

Of all the diseases that can afflict humankind, none is as devastating as ESRD. The process of staying alive involves complicated and repeated treatment with dialysis, or a renal transplant with lifelong testing and treatment to prevent rejection of the transplanted kidney that is not one’s own. Both these options are extremely costly, though in recent years they have been provided free or at subsidised cost, to some patients, by some state governments and the Central Government in India. Most often the onset is gradual and the patient knows of the illness and gradually progresses to the end-stage, giving him or her and the family time to understand the options for treatment and to make the best possible arrangements. However, there is a small subset of patients who are asymptomatic and quite unaware of the presence of the disease, and are suddenly hit with the catastrophic onset of symptoms. This book purports to describe, in his own words, the experience of one such patient, a boy of 15 years, who has a brief illness and is diagnosed with ESRD. The author and the translator skilfully take us through the symptoms and thoughts of the patient and his relations as they deal with dialysis and make plans for long-term treatment. The patient’s mother donates a kidney to him, and he receives the organ after surgery on both. At no stage does the narration pall, even for a nephrologist like me who has experienced this situation some thousands of times in the course of a long career. I visualize this book becoming a guide for many families that have a kidney patient to be looked after.

After a few days of good function, there is a setback, and the serum creatinine begins to rise. There is no response to an increase in the dose of medicines, and the patient is advised to undergo a kidney biopsy to determine the cause of malfunction and modify treatment. The book ends abruptly as the boy’s father is trying to raise a loan to pay for the procedure.

A word about the translation. It is absolutely smooth, and gives the impression that the book was originally written in English. That is the acme of the translator’s art and skill.

I do find some shortcomings. We end the reading of the book with unanswered questions. This is not a mystery novel. The author has got us interested in the patient and his family, and we are entitled to know the outcome. Did the father raise the loan to pay for the biopsy? I expect he should have succeeded, as he managed to collect the far larger amount needed for dialysis and transplantation. The vast majority of transplants from a young mother to her son would be successful, and would keep him alive and well for several decades, to grow into adulthood and lead a normal life. It would be a rare tragedy if this transplant were to be rejected or to fail for some other reason. Why keep us in the dark? The author should have brought the story to its natural conclusion. He could have given us a bad biopsy report and ended with a tragic failure, or he could have told us that the kidney function was brought back to normal with the appropriate treatment. A reader who has spent some hours reading the book deserves to know the answer.

That ends the book review. However, having retired after 52 years in the very active practice of nephrology, let me give you a few words of free advice. No-one is too young or too old to develop ESRD. It is better to detect it early and not be ambushed by suddenly finding oneself in a terminal state. A simple urine test for protein and sugar and a blood pressure recording once a year from birth to death will detect kidney disease if it exists, or a predisposition to develop it, at negligible cost, and you can seek appropriate treatment. It is difficult to record blood pressure accurately in an infant under the age of 5 years, so you could omit that test till the child is over that age.

Comments (0)