This study surveys the extensive international scientific literature and health management initiatives relating to impacts of highly pathogenic avian influenza A HPAI) viruses on pinnipeds in order to reinforce strategies for the conservation of the endangered Caspian seal (Pusa caspica), under threat from the HPAI H5N1 subtype transmitted from infected avifauna which share its haul-out habitats. It is intended to facilitate the understanding of the widespread recent deaths in pinnipeds associated with the spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza A viruses by providing a detailed global timeline of outbreaks together with their location, the clinical pathologies of dead or stranded pinnipeds and virological analyses of samples taken from them. With an extensive current bibliography, it is intended primarily as a working guide or “one stop bird flu information base” for those engaged in the rescue and conservation of pinnipeds, be this from the practical point of view of a field worker or from the perspective of an environmental manager or policy maker, with particular emphasis placed on recent and potential impacts of viral zoonoses on the Caspian seal and associated bird life, both major indicators of the state of the Caspian Sea’s littoral and marine ecosystem.

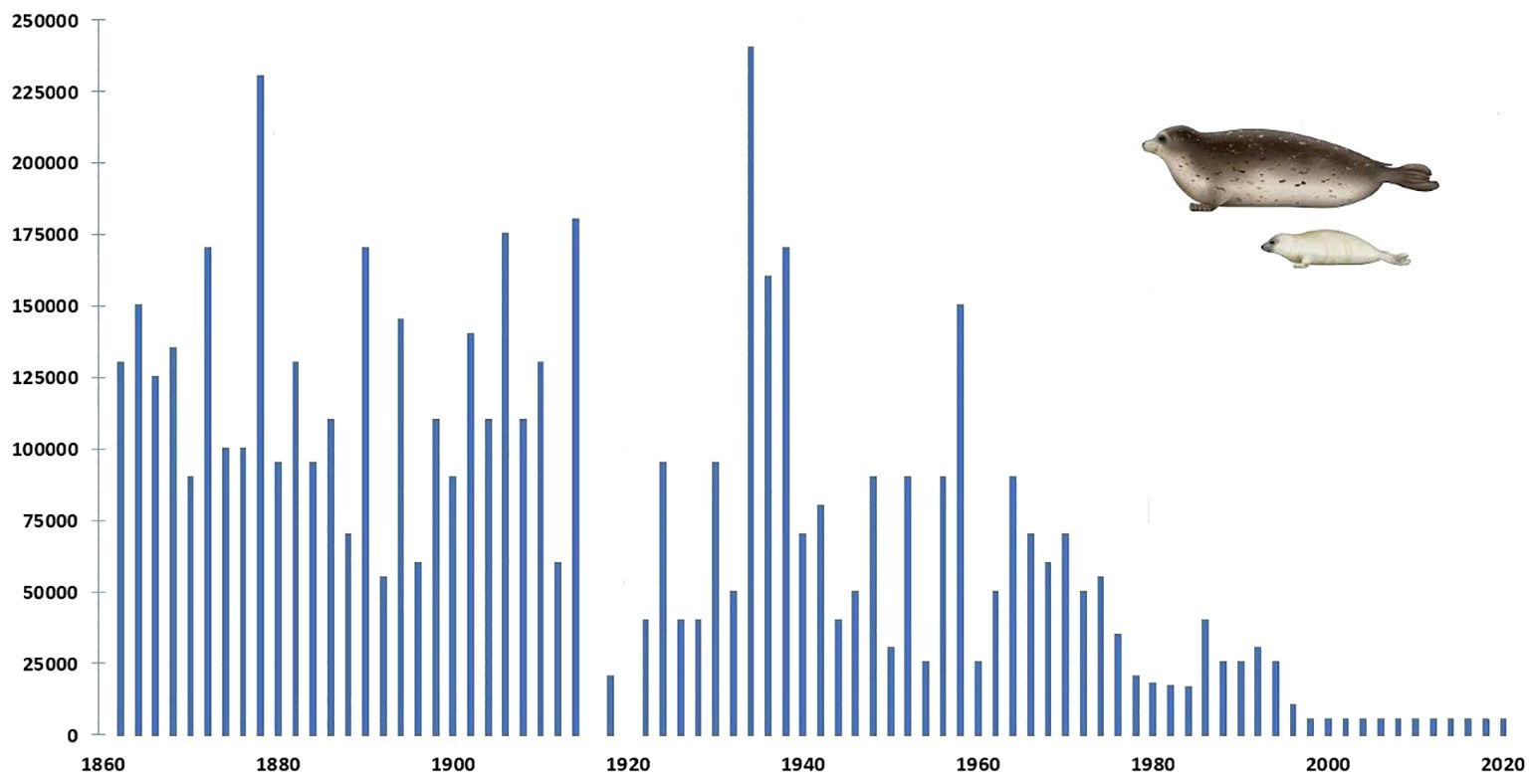

The Caspian sea region: historical depopulation of Caspian sealsThe population of the Caspian seal (Pusa caspica) declined from an estimated one million at the end of the 19th century to some 50,000 in the first decade of the 21st century, primarily due to state sanctioned “harvesting” (Dorofeev and Freiman, 1928; Roganov, 1932; Badamshin, 1969), (Figure 1) but also for a range of other reasons which have increasingly impacted on its viability. The dynamics of many of these are as yet not adequately understood. However, almost all impacts have some anthropogenic element: ecological disturbance, climate-change related, epidemiological, overfishing, entanglement in marine litter and nets, habitat degradation, marine pollutants, disruption of natural food resources, including due to invasion of non-endemic species. The first recorded mass mortality of Caspian seals occurred on the Tyuleniy (Seal) islands of Dagestan, Russia in 1931 (Timoshenko, 1969; Kydyrmanov et al., 2023). Further mass seal deaths of varying proportions were recorded in 1955-56, 1997, 2000, 2007, 2020 and 2022.

Figure 1 Graph plotting annual numbers of Caspian seals harvested between 1867 and 2020 (none were culled after 2000). Compiled from: FAO Fishsta+; Caspian Environment Programme, Transboundary Analysis Revisit (2007); and Härkönen et al. (2012). The latter assessed significantly less seals born in most of these years than were harvested.

Following particularly large mass mortality events along the northern and central Caspian Sea coast in 2022 (numbered as many as 10,000) local fisherman and specialists in the conservation of this iconic pinniped have observed a very substantial decrease in its numbers in Russian waters. Studies internationally have observed a correlation between deaths in aquatic birds due to various strains of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Viruses (HPAIV) and mass deaths of seals in shared habitats also due to HPAIV. Mass and individual deaths in aquatic birds due to the HPAI H5N1 subtype have recently been recorded in habitats also frequented by the Caspian seal (as reported in detail below).

Character and etiology of avian influenza viruses and their transmission to pinnipedsAvian influenza viruses (AIVs) are type A influenza viruses of avifauna from which all influenza A viruses affecting other animals are thought to have derived, regardless of their host species (EU, 2006; Taubenberger, 2008; Van Tam and Sellwood, 2010; DeLiberto et al., 2011; OIE, 2015). AIVs are widespread and in circulation amongst many wild bird species, in particular aquatic birds of the Anseriformes (mainly ducks, geese and swans) and Charadriiformes (mainly pelagic birds, gulls, terns [Laridae] and waders) orders, which constitute their principal natural host reservoirs (Easterday et al., 2006; Stallknecht and Brown, 2009; Curran et al., 2013; Sobolev et al., 2016; Gulyaeva et al., 2021).

Avian influenza viruses (AIVs) usually result in very mild gastrointestinal tract infections in wild avifauna, which result in low and temporary immunity, with co-circulation of and co-infection with multiple other strains and subtypes. As infected birds usually remain asymptomatic, AIVs may circulate undetected. During a brief period of infection (c. one month) the virus replicates in the gut and is then excreted in the feces at very high levels. Wild avifauna can congregate in large numbers before prior or during migration, thus providing optimal conditions for the transmission and mixing of AIVs and thus maintaining the reservoir in certain species (Van Tam and Sellwood, 2010).

Those AIVs which lead to mild or no disease and may circulate without being detected are considered as low pathogenic avian influenza viruses (LPAIVs) (Van Tam and Sellwood, 2010). However, LPAIV subtypes H5 and H7 may evolve towards highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses (HPAIVs) when transmitted into farmed poultry populations. Thus, the HPAIV H5N1 subtype which emerged in South-East China in 1997 and has since continued to circulate in poultry, has led to hundreds of cases of severe respiratory infection in humans and systemic disease in a wide range of wild, farmed and domestic avian and mammalian species (Chen et al., 2017; Hill et al., 2018; Sharshov et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2022) (see further below).

The adherence of migratory aquatic avifauna to habitual transcontinental and intercontinental flyways has resulted in AIVs being phylogenetically separated into 2 genetically distinct lineages, Eurasian (EA) and North American (NA) (Webster et al., 1992). In zones where flyways overlap, AIVs with gene segments of both NA and EA lineages have been isolated, although these instances are rare. The monitoring of wild bird viruses in western (Alaska) and eastern (Newfoundland) North America has identified a significant majority of AIVs which have whole-genome segments from EA lineage viruses but only very infrequently have reassortant AIVs s with both EA and NA gene segment constellations having been isolated from them (Huang et al., 2014; Ramey et al., 2015). In 2014, for example, the H5N8 virus, a reassortant of goose/Guangdong/1/96 (Gs/GD) H5Nx lineage was identified in wild aquatic birds along the North American sector of the Pacific Americas littoral flyway. NA lineage AIVs reasserted with this particular subtype, leading to severe losses in the Canadian and United States poultry industry (Berhane et al., 2022). See also Vahlenkamp and Harder (2006), Ip et al. (2008), Wille et al. (2011a, b) and Lee et al. (2015).

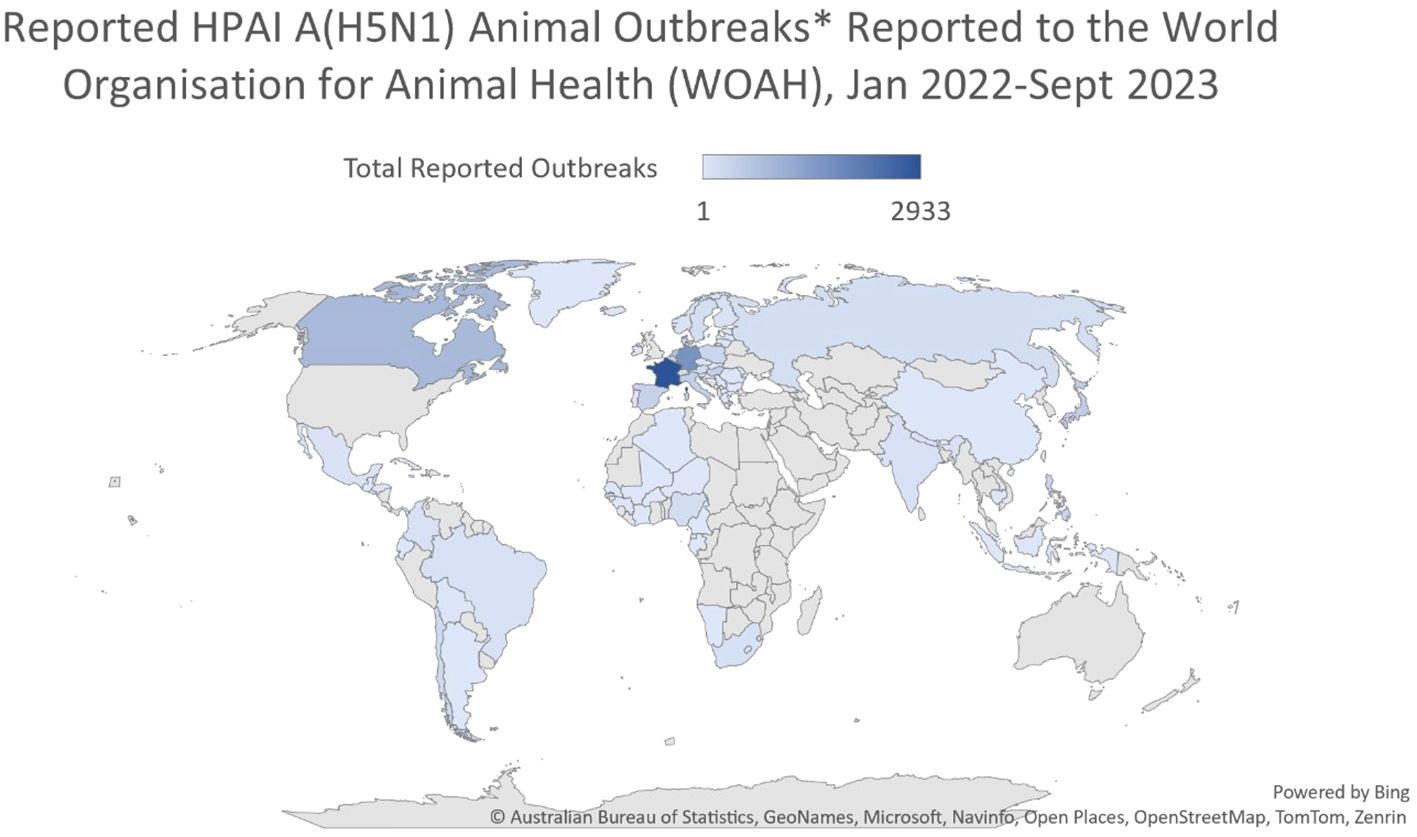

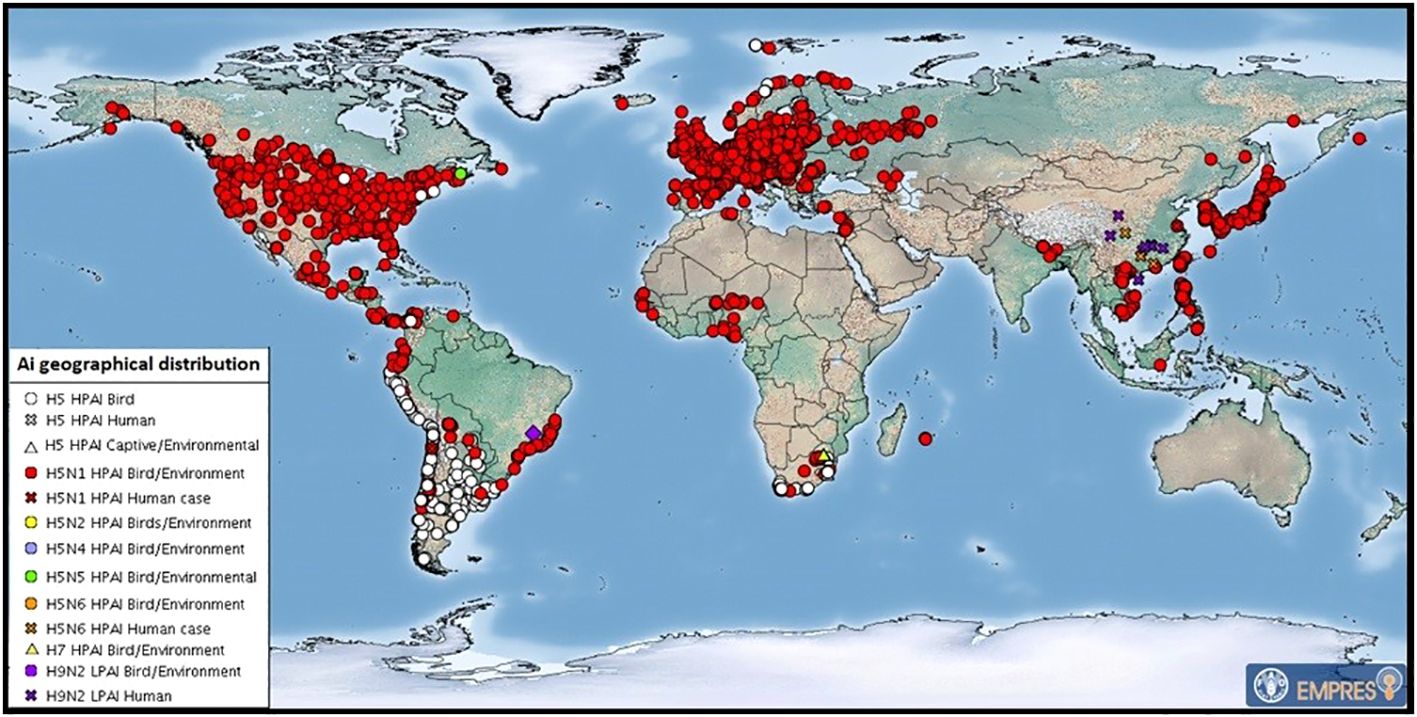

AIVs originating in wild avifauna can breach the host species barrier and infect certain terrestrial mammals as sporadic cases of infection, self-limiting epidemics, or sustained epidemics that may eventually develop into recurring epidemics through reassortment. After crossing the species barrier, some AIVs which cross the species interface can become established in new hosts and circulate independently of their reservoir hosts (Hatta et al., 2001; Berhane et al., 2022). Since 2021, there has been a significant change in the eco-geography of the highly pathogenic avian influenza A subtype H5N1 (particularly clade 2.3.4.4b), which is currently circulating on five continents (Kilpatrick et al., 2006; Lloren et al., 2017; Isoda et al., 2022) (Figures 2, 3).

Figure 2 Reported HPAI A(H5N1) animal outbreaks reported to the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH), January 2022-June 2023. After: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Geonames, Microsoft, Navinfo, Open Street Map, Tom Tom, Zenrin.

Figure 3 July 2023 map of global distribution of AIV with zoonotic potential (including H5Nx HPAI viruses) since 1 October 2022. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. These are outbreaks in animals officially reported since the previous update (22 HPAI subtypes: H5 (untyped) (53), H5N1 (625), H5N5 (2), H5N6 (1) and H7 (4). After FAO: https://www.fao.org/animal-health/situation-updates/global-aiv-with-zoonotic-potential/en.

The planet’s air and water together are serving as an interconnected environmental continuum within which certain avian and mammalian taxa (including marine mammals) are serving both as a contact source and a sink for avian influenza viruses which are being transmitted uni-directionally, contra-directionally (bi-directionally), and in multiple directions as they seasonally migrate and also move long-habitual locations in response to climate change or in search of accessible food sources (Breban et al., 2009; Tian et al., 2014). The HPAI H5N1 virus is reaching places previously not known to have been exposed to such a virulent AIV strain and has the potential to spread into endangered species with major impacts on biodiversity.

Various species of marine mammals have been shown to be vulnerable to AIV infection, particularly pinnipeds, which are exposed at haul-out and breeding sites and interface ecologically with wild birds and with other infected sympatric mammalian species (Venkatesh et al., 2020). As laid out in the global timeline of seal infections below, previous outbreaks and individually reported infections have shown that seals may be affected by and die as a result of infection with H10N7, H3N8, H7N7, H4N6, and other AIVs (Venkatesh et al., 2020). As indicated above, AIVs in birds replicate principally in the gastrointestinal tract intestine and is transmitted orally or via feces and other bodily secretions (respiratory tropism and oropharyngeal shedding have also been observed) (Webster et al., 1978; Daoust et al., 2011; Daoust et al., 2013; França et al., 2012; Höfle et al., 2012). Avian influenza viruses can survive in the natural environment for quite long periods (Stallknecht et al., 1990; Brown et al., 2009) in conditions which permit exchange of viruses between pinnipeds and aquatic avifauna, which share habitats and nutritional sources. See also Harvell et al., 1999; Horm et al., 2012).

A number of instances of marine mammal infection caused by many AIV subtypes, including H1N1, H3N3, H3N8, H4N5, H4N6, H7N7, and H10N7, have been substantiated with effects ranging from mass mortalities to sub-clinical; in a majority of these infections avian influenza was determined as the source (Webster et al., 1981a; Danner et al., 1998; Ohishi, 2002; Ramis et al., 2012; White, 2013; Karlsson et al., 2014; Fereidouni et al., 2014; Berhane et al., 2022). There are also studies which indicate that the grey seal (Halichoerius grypus) may constitute an endemic viral reservoir from which influenza A viruses can be transmitted in coastal environments to other mammals and aquatic avifauna and may potentially also infect humans (Duignan et al., 1995; Duignan et al., 1997; Herfst et al., 2012; Puryear et al., 2016; Dittrich et al., 2018). In this regard, levels of seroprevalence in healthy grey seal populations (20–26%) (Bodewes et al., 2015a, b; Puryear et al., 2016) have been found to be comparable with those of wild bird populations (31–60%) depending on other factors such as species, geography, season, etc. (Fereidouni et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2013; Curran et al., 2015; Venkatesh et al., 2020). Nevertheless, as White (2013) suggests, it seems that severe AIV infection is sporadic in pinnipeds and does not usually result in mass mortalities. Further investigation is required to explore the causes, which are likely to be multifactorial of such epizootics and the evolution of influenza viruses and associated mortality events in pinnipeds (White, 2013; Baz et al., 2015; Belser et al., 2011).

Recent significant Caspian seal and wild avifauna mortality events in the Caspian sea region 2022-2023The Caspian seal (Pusa caspica) is the only marine mammal inhabiting the Caspian Sea (Eybatov, 2010; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2023). As the top predator in the marine food chain, the state of its population is a key indicator of the integrity of the region’s biodiversity. It has been classified as endangered in the Red List of Threatened Species of the IUCN since 2008.

Between 31 March and 2 May 2022, over 832 dead Caspian seals were found along the Caspian Sea coast of the Mangystau region of Kazakhstan. Carcasses found by Kazakhstan’s Institute of Hydrobiology and Ecology were in varying states of decomposition and may have died at different times and of varying causes, including external signs of pneumonia (possibly symptomatic of an avian influenza infection). In such a situation, it was impossible to take useful histological, virological and other samples. Later in the year, in November 2022, the Fishery Committee of the Kazakhstan Ministry of Ecology, Geology and Natural Resources reported their representatives had found 141 dead Caspian seals on the Kazakhstan coast between Bautino and Fort-Shevchenko on the Tyub-Karagan peninsula. Specialists from scientific organizations, including the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (NIBIO), and Kazakhtstan government entities, concluded that the principal cause of death for most of the seals was virus-associated acute pneumonia as a result of an outbreak of mixed influenza and morbillivirus infection (https://partner.sciencenorway.no/climate-endangered-species-environment/norwegian-kazakhstan-research-collaboration-aims-to-save-endangered-seal-species/2164060 Accessed 09.10.2023).

Since that mass mortality event, another was recorded in Kazakhstan coastal areas between March and early June 2023 numbering 343 deal seals (including 73 pups) (http://kaspika.org/ru/2023/06/09/hundreds-of-dead-caspian-seals-in-kazakhstan-1/Accessed 09.10.2023). A determination of the cause or causes has not yet been published.

In early December 2022, thousands of dead seals in varying advanced states of decomposition were also found along the coast of Dagestan, Russia, mainly between Izberbash and Sulak. Specialists from the Institute of Ecology and Sustainable Development (DSU) and representatives of the Dagestan Ministry of Natural Resources and Ecology examined more than 100 dead seals and took samples of pathological material from six of the least decomposed carcasses for toxicological and virological analyses (five of which proved unsuitable for laboratory analysis, as reflected in the results given below). External examination of the animals showed that most had a characteristic discharge from the nasal and oral cavities in the form of bloody secretions, which, according to studies referenced below, are typical when animals die from asphyxiation as a result of respiratory tract infection when infected with avian influenza.

Subsequently, samples taken for virological analyses on 10 December 2022, were sent to the Research Institute of Virology (FRCFTM SB RAS) in Novosibirsk for testing for the presence of avian influenza and the morbillivirus CVD. An internal report of the Research Institute of Virology dated 31 January 2023 states that: (1) Laboratory analysis using PCR with primers for morbilliviruses, determined that all samples gave a negative result; that is RNA of morbilliviruses (including canine distemper and seal distemper) was not detected; and (b) in analysis using PCR with primers for influenza type A virus, samples from five animals were negative, while samples from one seal (internal organs and nasal swabs) were positive for influenza type A virus.

However, due to the fact that all the corpses of animals discovered, including those from which samples were taken, had died more than a day before the collection of pathological material, inhibiting isolation of influenza A virus RNA and specification of the subtype, it was concluded that further investigation was required, optimally through testing for antibodies in surviving seals in the same Russian waters.

In May 2022, specialists from the Research Institute of Virology, Federal Centre of Fundamental and Translational Medicine, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences (FRCFTM SB RAS), also investigated a considerable number of ill and dead Caspian terns (Hydroprogne caspia) and a lesser number of great black-headed gulls (Larus ichthyaetus), Caspian gulls (Larus cachinnans) and Dalmatian pelicans (Pelecanus crispus) on Maliy Zhemchuzhniy Island, a major intersection of migratory flyways north-east, north-west and south (Vilkov, 2016a; Veen et al., 2005) (Figure 4) and the major haul-out site of the Caspian seal in the Russian northern waters of the Caspian Sea (Krilov, 1976, 1982; Khuraskin and Pochtoeva, 1986) (Figures 5, 6). This investigation was in response to notification by the Institute of Ecology and Sustainable Development (DSU) by Astrakhan State Nature Biosphere Reserve (ASNBS) authorities of this outbreak in the Maliy Zhemchuzhniy Island Specially Protected Natural Area of Federal Significance which they administer.

Figure 5 Southern tip of Maliy Zhemchuzhniy Island, northern Caspian Sea, Russia, showing Caspian seals in proximity to aquatic birds and their breeding colonies (great black-headed gulls, Caspian gulls and Caspian terns). Photo: ASNBR, 11 April 2020.

Figure 6 Northern tip of Maliy Zhemchuzhniy Island, northern Caspian Sea, Russia, showing Caspian seals in close proximity to aquatic birds (great cormorants, Caspian gulls and Caspian terns). Photo: ASNBR, 11 April 2020.

During the 20th century, scientists characterized Maliy Zhemchuzhniy Island as a location where sick seals lingered after winter when healthy seals dispersed elsewhere in the Caspian Sea. Considerable research was undertaken in the later years of the USSR in documenting the gulls and terns frequenting the island and identifying viruses they carried (Andreev et al., 1980; Aristova et al., 1982, 1986). The island is the location of the largest breeding colony of great black-headed gulls documented as nesting in the Caspian region.

In the period April-May 2022, it was calculated that over 30,000 birds had died or were suffering on the island. According to ASNBR observations, some weakened birds stood and showed no fear on approach by humans, while others were losing coordination and tumbled. Their external neurological behavioral symptoms were similar to those of seals suffering from a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus strain (see further below). Diarrhea was the principal externally observable clinical symptom, although there was no abnormal discharge of oral mucosa. It was notable that dead birds had well-groomed feathers, indicating that each individual had rapidly succumbed to the virus. Among the terns and gulls nearly all chicks died during the nesting period: no live chicks were observed on the island later in the 2022 nesting period.

From samples taken from birds on the island in May 2022 and analyzed by the Research Institute of Virology (FRCFTM SB RAS), the H5N1 subtype was determined as the cause of the infections and is the outcome of sequential reassortment of multiple genetic variants of LPAI and HPAI viruses. The research indicates that in the fall of 2021, the HPAI virus moved along with migrating birds to their wintering sites, and in the winter of 2022 was detected in Israel. With the spring migration of 2022, it spread from the Middle East to nesting areas, causing the death of wild birds on Maliy Zhemchuzhniy Island (Sobolev et al., 2023).

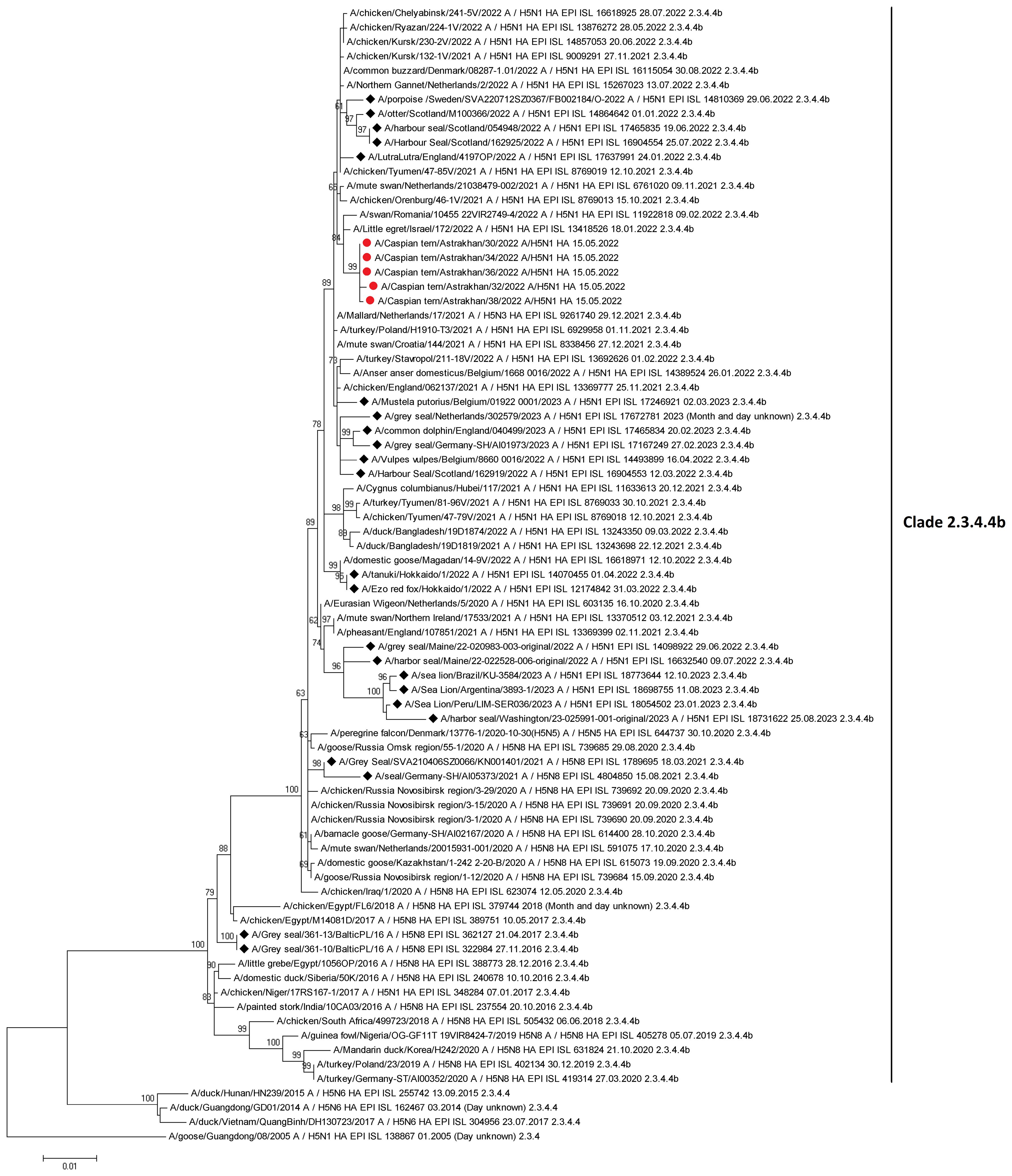

There are currently 80 sequences of H5Nx influenza viruses isolated from seals and sea lions in the GISAID database, confirming the ability of the virus to infect these animals. Based on the results obtained by the authors of the article, as well as data posted in the GISAID database, we conducted a phylogenetic analysis for the HA gene of highly pathogenic influenza viruses found not only in birds, but also in mammals (Figure 7). According to the analysis of highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza viruses of clade 2.3.4.4b, isolated from mammals (including marine mammals), they are phylogenetically closely related to those circulating among birds, including those that caused mass deaths on Maliy Zhemchuzhniy Island. Thus, there is a possibility that when seals come into contact with aquatic avifauna infected with a highly pathogenic influenza virus, interspecific transmission of the pathogen is possible.

Figure 7 Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of the hemagglutinin segment. Circles indicate HPAI H5N1 virus strains detected in birds on Maliy Zhemchuzhniy Island. Rhombuses indicate H5Nx viruses of clade 2.3.4.4b isolated from mammals (including marine mammals). The multiple alignment was performed using MUSCLE. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic analysis was generated and visualized by MEGA5 using the general time-reversible nucleotide substitution model. Bootstrap support values were generated using 500 rapid bootstrap replicates.

Here it should be noted that hundreds of deal Caspian seals were found on northern Dagestan shores in December 2023, clinically presenting similar symptoms to those sampled in the same region during the mass mortality of late December 2022.

Other detections of HxNx strains in the Caspian region 2004-2023Between 14-17 November 2005, an epizootic among mute swans occurred in the Russian sector of the lower Volga River delta. More than 250 dead swans were found in the Kamizyakskiy district, Astrakhan oblast and about 150 dead swans in the Laganskiy district of the Republic of Kalmykia. Samples from sick and recently died swans were analyzed by the D.I. Ivanov Institute of Virology, Russian Academy of Medical Sciences: ten HPAI H5N1 strains were isolated and deposited in the State Collection of Viruses of the Russian Federation (Lvov et al., 2006).

On 19 June 2022, two wild animals (species unidentified but probably waterbirds) were reported dead in north Caspian Sea waters off the Ural River delta near Atyrau, Kazakhstan. A report (Report ID FUR_157724) from the Kazakhstan authorities to the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) states that the cause was the H5 strain (N untyped) of avian influenza, as detected by the Republican State Enterprise National Reference Centre laboratory. Testing was done through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (https://wahis.woah.org/#/in-review/4503?fromPage=event-dashboard-url). This identification was the latest in a series of Kazakh government laboratory AIV isolations from samples taken from water and shore birds along the Kazakhstan northern Caspian littoral in 2004 and later in 2006, as follows:

At the Institute of Microbiology and Virology, Almaty, Kazakhstan: A/great black-bed gull/Atyrau/743/2004 (H13N6)A/great black-headed gull/Atyrau/744/2004 (H13N6); A/great black-headed gull/Atyrau/767/2004(H13N6); A/great black-headed gull/Atyrau/773/2004(H13N6); A/common pochard/Aktau/1455/2006(H4N6); A/coot/Aktau/1454/2006(H4N6); and A/mute swan/Aktau/1460/2006(Y5N1) were identified; and A/swan/Mangystau/3/2006(H5N1) was identified at the Institute for Biological Safety Problems, Gvardeiskiy, Zhambyl Oblast (Bogoyavlenskiy et al., 2011). The latter was from a wild mute swan found dead on the coast of the Mangystau region in March 2006, the virus responsible being isolated and characterized by the Laboratory of Ecology and Viruses, Institute of Microbiology and Virology, Almaty and the Institute for Biological Safety Problems, Gvardeiskiy, Zhambyl Oblast. 70 wild birds were later found dead from H5N1 in this same area (Tabynov et al., 2008; Kydyrbaev et al., 2010). Phylogenetic analysis indicated that this subtype differs from EMA groups of HPAI H5N1 viruses and has NS2A NS2A genotype typical for Gs/Gd-like strains (Bogoyavlenskiy et al., 2011; Chervyakova et al., 2011). This led Chervyakova et al. to consider that this subtype may have been transmitted by birds from Europe (Sweden) along the Black Sea/Mediterranean avian flyways. These overlap with the Eurasia-Africa flyway in the Caspian region. See also Sayatov et al., 2007; Kydyrbayev et al., 2010; Bogoyavlenskiy et al., 2012; Tabynov et al., 2014; Burashev et al., 2020.

From the point of view of the evolution of avian influenza viruses and their transfer to other geographical regions, researchers of the Federal Centre of Animal Health, Vladimir, Russia (Zinyakov et al., 2022) have provided data for H5N5 viruses isolated from birds sampled in the northern Caspian region in 2020-2021 as follow: A/dalmatian pelican/Astrakhan/417-2/2021(H5N5) (recovered on 1 April 2021); A/dalmatian pelican/Astrakhan/417-1/2021(H5N5) (recovered on 1 April 2021); A/pelican/Dagestan/397-1/2021(H5N5) (recovered on 6 April 2021); A/gull/Dagestan/397-2/2021(H5N5) (recovered on 6 April 2021); A/waterfowl/Russia/1526-4/2021(H5N5) (recovered on 28 September 2021); A/shelduck/Kalmykia/1814-1/2021 (H5N5) (recovered on 8 November 2021), which the researchers have collectively referred to as Caspian Region Viruses (VCR). For these subtypes, a similar clustering of genomic segments was determined with isolates of the H5N5 subtype influenza A virus, which were identified in Europe in winter and spring 2021. Zinyakov et al. (2022) state that “phylogenetic analysis of nucleotide sequences of entire viral genomes belonging to the H5N5 subtype suggests that they all evolved through the reassortment of HPAI H5N8 with one unidentified N5 subtype virus. This was confirmed by the dense clustering of viruses carrying the HA and MP genes for H5N5 and HPAI of the H5N8 subtype, previously identified in the Russian Federation (an exception being the avian influenza virus A/eagle/Hungary/8569/2021).” H5N5 subtype isolates recovered in Europe in autumn 2020 were also included in the analysis. The results obtained indicated that the H5N5 subtype viruses detected in Europe and Russia in 2021 emerged in autumn 2020 (Zinyakov et al., 2022).

Laridae (gulls and terns in particular) constitute one of the principal reservoirs of AIVs. Their eco-geographic role in the global dynamics of the spread of AIVs, are significant but yet distinct from those of wild waterfowl (Kawaoka et al., 1988; Perkins and Swayne, 2002; Fouchier et al., 2005; Wille et al., 2011a; Ratanakorn et al., 2012; Tønnessen et al., 2013; Verhagen et al., 2014; Wille et al., 2014; Arnal et al., 2015; Benkaroun et al., 2016; Lang et al., 2016; Alkie et al., 2022, 2023; Lean et al., 2023). Although gulls are mainly vectors for the H13 and H16 subtypes, they have been shown to also be infected by other subtypes. They also often carry AIVs with mixtures of genes of different geographic phylogenetic lineages (e.g. EA and NA). A range of viruses detected in gulls and terns globally have been shown to possess very high phylogenetic affinities to viruses identified in other host taxa, thus demonstrating the potential for gulls to serve as HPAI virus carriers, which disseminate viruses across long distances and contribute to the genesis of pandemic variants. For instance, Huang et al. (2014) provide a chronology of the evolution of an entirely Eurasian gull virus (H16N3) which was isolated in North America. Genetic tracing indicates that the Caspian Sea was an important zone in the generation of this virus and that an analysis of AIVs isolated in certain tern species also indicates that the Caspian region plays in role in the generation and transmission of novel strains. Thus an analysis of the geographic and chronological progression of gull virus genes which contributed to the genesis of the Eurasian H16N3 gull virus isolated in Newfoundland, Canada, points to an origin in coastal Astrakhan in Russia in 1983, then in Scandinavia in 2006-2009, and then in Iceland and Newfoundland, Canada in 2010 (Huang et al., 2014; Benkaroun et al., 2016).

On 9 February 2023, the responsible Russian state agricultural authority, Rosselkhoznadzor, also reported that the North Caucasus Inter-Regional Veterinary Laboratory detected influenza A virus of subtype H5 in a sample taken from a dead swan (species unidentified) near Solnechnoe, Khasavyurtovskiy District, Dagestan, on 3 February 2023. This provided yet further evidence of the presence of avian H5 viruses in the region (unpublished internal report). A later report dated 14 February 2023 to the WOAH (Report ID FUR_159296) states that five mute swans (Cygnus olor) were found dead in that location on 12 January 2023, the Federal Centre for Animal Health (ARRIAH) reporting that the highly pathogenic avian influenza subtype had been detected through real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction testing (https://wahis.woah.org/#/in-review/4846?fromPage=event-dashboard-url).

Studies of Caspian seals for avian influenza A viruses: a chronologyThe first studies of viruses in Caspian seals focused on AIV circulation, Yamnikova et al. reported negative results for embryonated chicken egg cultures of 152 samples collected from seals between 1976 and 1999 (Yamnikova et al., 2001; Kydyrmanov et al., 2023). Later, Ohishi et al. (2002) detected antibodies to H3N2, H2N2, H3N8, and influenza B viruses in Caspian seals. They reported that “antibodies to influenza A virus were detected in 54%, 57%, 40% and 26% of serum samples collected in 1993, 1997, 1998 and 2000 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). In a hemagglutination-inhibition (HI) test using H1-H15 reference influenza A viruses as antigens, more than half of the examined ELISA-positive sera reacted with an H3N2 prototype strain A/Aichi/2/68. These sera were then examined by HI testing with a series of naturally occurring antigenic variants of the human H3N2 virus and H3 viruses of swine, duck, and equine origin. The sera reacted strongly with the A/Bangkok/1/79 (H3N2) strain, which was prevalent in humans in 1979–1981. The results indicate that the human A/Bangkok/1/79-like virus was probably transmitted to Caspian seals in the early 1980s, and was circulated in the seal population. Antibodies to influenza B virus were detected by ELISA in 14% and 10% of serum samples collected from Caspian seals in 1997 and 2000, respectively.” The researchers concluded that the Caspian seal might be a reservoir of both influenza A and B viruses which had originated from humans (Ohishi et al., 2002).

These findings have been since supplemented by those of a collaborative research team from the Institute of Ecology and Sustainable Development (DSU) and the Research Institute of Virology (FRCFTM SB RAS), which isolated an avian-like H4N6 virus A(H4N6)T1 influenza A virus in a Caspian seal in Dagestan in 2012. The virus was considered to have probably originated from birds. The researchers emphasized that the role of pinnipeds “as intermediate hosts or carriers of potential zoonotic pathogens remains poorly understood (Fereidouni et al., 2014), highlighting a necessity for the long-term, systematic surveillance of influenza virus in marine mammals.” (Gulyaeva et al., 2021; Gulyaeva et al., 2018a, b).

After the widely-circulated reports of the mass mortality of seals in Dagestan in early December 2022, the Kaspika Caspian Seals Conservation Agency reported that specialists from the Biodiversity Conservation Service at the Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources, Food Safety Agency and the Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Azerbaijan inspected the entire Azerbaijani coast of the Caspian Sea to identify possible seal mortalities and to determine the causes.

Seventeen dead seals were found by the team in the Khachmaz region (north Azerbaijan) and twenty-seven along the coasts of the Absheron Peninsula. Tissues and internal organs were sampled for toxicological, virological and bacteriological analyses. (http://kaspika.org/en/2022/12/14/monitoring-of-dead-seals-inazerbaijan-2/). The results have not yet been published.

HPAI H5N1 deaths of northern fur seals and Stellar Sea lions and aquatic avifauna in eastern Russia and multiple wild avifauna fatalities due to the subtype in central and northern Russia 2023In August 2023, the death of a northern fur seal (Callorhinus ursinus) in Mordvinov Bay on Sakhalin Island in the Sea of Okhotsk in eastern Russia was attributed by the Russian Federal Centre for Animal Health as due to HPAI H5N1 and reported to the WOAH (Report FUR_162532). Multiple (more than 300) deaths of northern fur seals and Stellar sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus) were also reported in early August 2023 by nature conservationists removing marine litter and pinniped entanglements on the uninhabited Tyuleniy Island off the east coast of Salkhalin Island. Samples from dead animals were later taken for analysis by specialists of the Federal Supervisory Natural Resources Service (livescience.com/animals/seals/mystery-mass-death-of-seals-or-remote-uninhabited-siberian-island-under-investigation). See also, Permyakov et al. (2023).

Throughout the summer months of 2023, multiple cases of Laridae (species unidentified) dying of HPAI H5N1 in the Komi Republic, Novgorod and Murmansk oblasts (central and northern Russia) and the Primorskiy Krai (eastern Russian seaboard) were also reported to the WOAH. For the latter region an epidemiological comment was appended that during the active monitoring of avian influenza in wild birds, one sample out of ten demonstrated the H5N1 avian influenza virus genome (https://wahis.woah.org/#/event-management Accessed 08.10.2023).

Timeline of global (non-Caspian region) occurrences of seal mortalities attributed to avian influenza viruses and their clinical signs and pathologiesHistorically, epizootics with considerable mortalities in seal populations have been documented mainly along the shores of the USA and Europe. Such deaths have been mostly attributed to viral infections (Siebert et al., 2010), increasingly caused in recent years by avian or avian-like influenza viruses.

Below is presented a global timeline of published AIV outbreaks or serological analyses with the geographical location of seals examined, the gross external clinical signs and symptoms of diseased seals, the subsequent laboratory analytical pathology undertaken and subtype designation as well as key associated conclusions.

1979-1980: The first influenza epizootics recorded in any pinniped species were of acute hemorrhagic and interstitial pneumonia in harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) along the Massachusetts (New England) coast of the USA. From 1979 -1980 some 600 harbor seals died – c. 20% of the estimated seal population in this region. Investigations revealed that these respiratory infections were caused by “an H7N7 influenza virus (designated subtype A/Seal/Mass/1/80), which was repeatedly isolated from the lungs, brain, and hilar lymph nodes of dead seals sampled.” (White, 2013)” See also Geraci et al., 1982 and Hinshaw et al., 1984.

Since the 1979-1980 outbreak, mortalities in harbor seal populations along the coasts of the United States and Europe have been largely attributable to viral infections (Siebert et al., 2010).

Subsequently, influenza virus infection has been evidenced through many influenza serotypes found through antibody and virus isolations from seal populations in many regions of the world. Serotypes of H5N1, H7N7, H4N5, H4N6, H3N8, and H3N3 have been isolated in harbor seals along the New England coast (White, 2013).

1982-1984: In 1981, no further increase in seal deaths or strandings was observed along New England shores. Between June 1982 and March 1983, more harbor seals were again found dead or dying of severe viral pneumonia along the New England Cape Cod coast (constituting a c. 2% to 4% mortality rate of the estimated regional seal population) (White, 2013). Although the pathology was similar, the strain of influenza A detected differed from that identified in the first 1979-1980 outbreak (Geraci et al., 1982; Hinshaw et al., 1984). From one sample from an emaciated adult seal stranded on Plum Island, Massachusetts in June 1982, Hinshaw et al. (1984) isolated an influenza A virus strain identified as H4N5, whose surface antigens had previously been detected only on avian viruses. These researchers observed that, “comparisons with other avian strains indicated that the hemagglutinin of this seal virus was closely related to isolates from ducks, e.g. A/Dk/Alb/686/82 (H4N6), and turkeys, e.g., A/Ty/Mn/28/78 (H4N8), and that the neuraminidase was indistinguishable from the prototype for N5, i.e. A/Shearwater/Aust/1/75 (H6N5). These findings indicated that this new virus strain found in seals, A/Seal/Mass/133/82, was most closely related antigenically to recent avian isolates and was clearly different from the previous H7N7 seal isolates recovered from 1979 to 1980” (Hinshaw et al., 1984). Later, Callan et al. (1995) described influenza A strains H3N3 and H4N6 isolated from harbor seals with interstitial pneumonia. Together these findings led to the conclusion that seals are indeed susceptible to influenza A viruses, which seem to have originated from avian reservoirs (H4N5, H7N7, H4N6 and H3N3) occurring in nature (Callan et al., 1995). Hinshaw et al. (1984) considered that, “this susceptibility may be an example of the adaptation of avian viruses to mammals, which would represent an intermediate step in the evolution of new mammalian strains.”

1991-1992: The monitoring of virus infection of seals was continued after the association of influenza A virus with pneumonia epizootics in seals off the New England coast in 1979-1980 and 1982-1983. In January 1991 and January to February 1992, influenza A viruses were isolated by Callan et al. (1995) from seals that had died of pneumonia on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. They reported that, “Antigenic characterization identified two H4N6 and three H3N3 viruses. This was the first isolation of H3 influenza viruses from seals, although this subtype is frequently detected in birds, pigs, horses and humans. Hemagglutination inhibition assays of the H3 isolates showed two distinct antigenic reactivity patterns: one more similar to an avian reference virus (A/Duck/Ukraine/I/63) and one more similar to a human virus (A/Aichi/2/68). The hemagglutinin (HA) genes from two of the H3 seal viruses showing different antigenic reactivity (A/Seal/MA/3911/92 and A/Seal/MA/3984/92) were 99.7% identical, with four nucleotide differences accounting for four amino acid differences. Phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that both of these sequences were closely related to the sequence from the avian H3 virus, A/Mallard/New York/6874/78.” Callan et al. (1995) further suggested that this indicates that influenza A viruses of apparent avian origin, including the H3 subtype viruses, had continued to infect seals. See also White, 2013.

Siebert et al (Siebert et al., 2010 - referring to Kennedy-Stoskopf, 2001) concluded “that the influenza A viruses that were isolated from North American seals between 1979 and 1992 were antigenically and genetically most closely related to avian influenza viruses, which in this particular biogeographical region suggests frequent spill-overs from pelagic birds.” They stated that, “no evidence for stable circulating seal-adapted lineages of influenza A viruses has been obtained so far.”.

Siebert et al (Siebert et al., 2010 – referring to Webster et al., 1981b; Geraci et al., 1982; Hinshaw et al., 1984). further reported that, “In experimental inoculation trials, all isolates from infected harbor seals in this region were able to replicate in ferrets, cats, pigs and phocid seals, including harbor, ringed and harp seals.” “Clinical signs of natural influenza infection were similar to those observed for Phocine Distemper Virus, which included dyspnea, lethargy, bloodstained nasal discharge and subcutaneous emphysema. Pulmonary lesions were predominantly characterized by necrotizing bronchitis and bronchiolitis and hemorrhagic alveolitis.” (Siebert et al., 2010 – referring to Geraci et al., 1982; Hinshaw et al., 1984).

2011: Again on the New England coast, in November 2011, 162 harbor seals were documented as having died of interstitial pneumonia, hemorrhagic alveolitis and necrotizing bronchitis pneumonia over a period of less than four months (four fold the expected approximate mortality rate in the region’s seal population). An H3N8 strain was isolated from several of the seals (Bodewes et al., 2015a, b). Antigenic and genetic analyses showed that all genes from each of the epizootic strains were of avian origin (Bodewes et al., 2015a, b; Lehnert et al., 2007; Munster et al., 2009; Pund et al., 2015; Bodewes et al., 2016; Hussein et al., 2016). Virus antigen and RNA was found in bronchiolar epithelium by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and in situ-hybridization (ISH) (Anthony et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2015).

Furthermore, a subsequent study by Mandler et al. (1990) demonstrated that the closest-matching avian strains to the 1980 H7N7 virus were from the same geographic region as the seal isolate. The H3N8 virus (A/harbor seal/New Hampshire/179629/2011) isolated from this outbreak demonstrated naturally acquired polymerase mammalian adaptation mutations, indicating that it is of interest for human public health (Hussein et al., 2016).

A number of pathological investigations on seals which later died during the 2014 northeastern European epizootic Seal/H10N7 outbreak (as outlined below), report similar necro-suppurative bronchopneumonial lesions with a bacterial co-infection (Zohari et al., 2014; Krog et al., 2015). This was a time during which the complete spectrum of virus-associated histological changes associated with viruses, viral antigen distribution and the target cell tropism of Seal/H10N7 in harbor seals were unknown. However, a 2016 publication by van den Brand et al. provides a more comprehensive description of histological, IHC, virological, bacteriological and parasitological findings in 16 naturally infected seals that were described previously by Bodewes and co-researchers (Bodewes et al., 2015a, b; Bodewes et al., 2016; van der Brand et al., 2016).

2014-2015: From spring 2014 to early 2015, some 3,000 harbor seals and grey seals reportedly died from avian influenza virus H10N7 in north-east Europe (Osterath, 2014). Initially, this subtype in seals was reported along the west Sweden and east Denmark coasts (Zohari et al., 2014; Krog et al., 2015), and then spread to seals off the coasts of west Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands (Common Wadden Sea Secretariat, 2014). It is estimated that over 10% of the population of these two seal species died in this outbreak (Bodewes et al., 2015a, b; Herfst et al., 2020).

At this time, Bodewes et al. (2015a) undertook histological, IHC, virological, bacteriological and parasitological examinations of 16 naturally infected seals that had been found to have a positive PCR for influenza A virus, as well as testing tracheal/throat swabs or lung tissue samples from a larger collection of dead or dying seals found along the German North Frisian coast and the island of Helgoland. They reported that, except for a single juvenile which was euthanized, all other seals had died of natural causes. All were reported to be in varying nutritional conditions, ranging from very poor to good. Gross findings in animals found dead comprised “poorly retracted lungs with severe congestion, alveolar and interstitial emphysema, alveolar edema, occasional diffuse consolidation, and multifocal firm nodular areas of grey-yellow discoloration with varying numbers of metazoan parasites. Other organs and tissues did not display significant changes.” (van der Brand et al., 2016).

2016-2017: In 2016 and 2017, during the HPAI H5N8 epizootic in Europe, an emerging, closely related subtype (clade 2.3.4.4b) was found in two grey seals on the Polish Baltic Sea coast (Shin et al., 2019). In November 2016, an emaciated, immature male grey seal was found dead on this coast in a condition of early decomposition. Pathologic findings by Shin et al. (2019) included a parasitic infestation of Halarachne halichoeri in the nasal cavity, lung, and gastrointestinal tract; agonal changes, including pulmonary edema and emphysema, were also documented.” A male pup, c. two months’ old, was then found in April 2017, also severely undernourished with signs of trauma and mild to severe parasitic infestation in its digestive tract. Analysis indicated the presence of several different bacteria. “Both seals were found to be infected by the same H5N8 virus (classified as H5N8/seal) with a multibasic cleavage site of PLREKRRKR/GLF in its HA protein, which fits the consensus sequence of a clade 2.3.4.b HPAI virus (WOAH, 2018). Phylogenetic analysis of the HA and NA segments further revealed that the isolate belonged to the clade 2.3.4.4b group of H5 HPAI viruses. Results of a homology BLAST search showed that this virus had a nucleotide homology of 99.7%–100% to AIVs viruses in circulation in wild aquatic avifauna in 2016 and 2017. This reassortant has been shown to be widespread and the cause of mass mortalities among waterfowl in many parts of the world, although no natural transmission from birds to marine mammals has yet been proven” (Shin et al., 2019).

In 2017, among AIVs which had already been identified in several seal species, evidenced by a pathogenicity spectrum from sub-clinical infection to mass mortality, an infection was identified by Venkatesh et al. (2020) in a 3-4-month-old grey seal pup, rescued from St Michael’s Mount, Cornwall, but which died shortly thereafter. The virus strain was revealed by nuceolitide sequencing to be of subtype H3N8. Through a GISAID database BLAST search and time-scaled phylogenetic analyses, the researchers inferred that. “this seal virus originated from un-sampled viruses, in local circulation in Northern Europe and likely to be from wild Anseriformes. On examining its protein alignments, several residue changes were revealed that did not occur in the avian viruses, including D701N in the PB2 segment, a rare mutation considered to be a characteristic of mammalian adaptation of avian viruses. Nevertheless, an avian influenza virus was not deemed to be the cause of death of the grey seal pup, as it had been reported to a rescue center after it was stranded, the AIV only being detected incidentally (Venkatesh et al., 2020).

2020-2021: Since autumn 2020 and following nearly 3 years of reduced AIV activity, Europe has been in the midst of another record-setting highly pathogenic avian H5Nx epizootic. However, unlike in previous events, increased signs are evident of avian flu spillover into mammalian species (European Food Safety Authority et al., 2021a, European Food Safety Authority et al., 2021b, European Food Safety Authority et al., 2021c). In 2020-2021 H5N1 infections were registered in wild birds and in more than 20 million farmed poultry in 28 European countries; effectively the most devastating HPAI epidemic that had ever occurred in Europe (Postel et al., 2022).

In Scotland from 2021 to early 2022, four dead seals (three harbor seals and one grey seal (found in Aberdeenshire, Highlands, Fife and Orkney) were tested positive for the HPAI H5N1 avian influenza virus through screenings undertaken by the Scottish Marine Animal Strandings Scheme (SMASS). At this time, the largest avian influenza outbreak in the British Isles had already spilled over into other mammals, about seventy having tested positive for the HPAI H5N1 subtype (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/bird-flu-avian-influenza-findings-in-non-avian-wildlife/confirmed-findings-of-influenza-of-avian-origin-in-non-avian-wildlife). See also Baily (2014).

In mid-August 2021, Postel et al. (2022), screening for viral pathogens, investigated unusual influenza A virus infections in three dead adult seals found on the German North Sea coast. In their brain tissue, high virus loads of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAI) H5N8 were detected with the isolation of different virus variants indicating high exposure to HPAIV in circulation among wild avifauna. However, no regional evidence was found for H5 specific antibodies in healthy seals. It was thus suggested by these researchers that avian virus replication in seals may allow HPAIVs to acquire mutations needed to adapt to mammalian hosts, as shown by PB2 627K variants detected in these cases.

As outlined above, during a previous AIV (H10N7) outbreak in seals associated with pneumonia and slightly increased mortality, and in the context of an HPAI H5N8 infection in the lung tissues of two dead grey seals found on the Polish Baltic coast in 2016, the same researchers had found no evidence for any brain infection. “The HPAIV H5N8 strain currently in circulation is reported to cause unusual neurological infection with fatal outcomes in four harbor seals and one grey seal kept in a wildlife rehabilitation center. Similar to very recently reported findings in captive seals in the UK, these results show that the HPAIV H5N8 of clade 2.3.4.4b can induce fatal CNS infections in seals under natural conditions. The genetic findings underlined the role of seals as a possible “adaptive vessel” for avian influenza viruses and the importance of monitoring wild bird and mammal populations accordingly.” (Postel et al., 2022).

In September 2021, the Danish Veterinary Consortium’s Centre for Diagnostics (Statens Serum Institute) at the T

Comments (0)